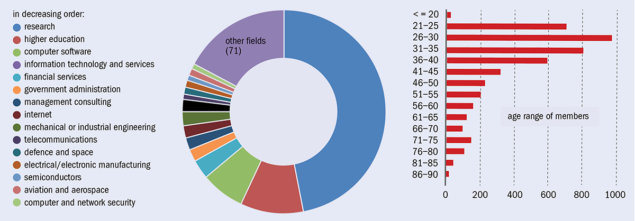

CERN has 65 years of history and more than 13,000 international users. The CERN Alumni Network, launched in June 2017 as a strategic objective of the CERN management, now has around 4600 members spanning all parts of the world. Alumni pursue careers across many fields, including industry, economics, information technology, medicine and finance. Several have gone on to launch successful start-ups, some of them directly applying CERN-inspired technologies.

So far, around 350 job opportunities, posted by alumni or companies aware of the skills and profiles developed at CERN, have been published on the alumni.cern platform. Approximately 25% of the jobs posted are for software developer/engineer positions, 16% for data science and 15% for IT engineering positions. Several members have already been successful in finding employment through the network.

Another objective of the alumni programme is to help early-career physicists make the transition from academia to industry if they choose to do so. Three highly successful “Moving out of academia” events have been held at CERN with the themes finance, big data and industrial engineering. Each involved inviting a panel of alumni working in a specific field to give candid and pragmatic advice, and was very well attended by soon-to-be CERN alumni, with more than 100 people at each event. In January the alumni network took part in an academia/industry event titled “Beyond the Lab – Astronomy and Particle Physics in Business” at the newly inaugurated Higgs Innovation Centre at the University of Edinburgh.

The network is still in its early days but has the potential to expand much further. Improving the number of alumni who have provided data (currently 37%) is an important aim for the coming years. Knowing where our alumni are located and their current professional activity allows us to reach out to them with relevant information, proposals or requests. Recently, to help demonstrate the impact of experience gained at CERN, we launched a campaign to invite those who have already signed up to update their profiles concerning their professional and educational experience. Increasing alumni interactions, engagement and empowerment is one of the most challenging objectives at this stage, as we are competing with many other communities and with mobile apps such as Facebook, WhatsApp and LinkedIn.

One very effective means for empowering local alumni communities are regional groups. At their own initiative, members have created seven of them (in Texas, New York, London, Eindhoven, Swiss Romandie, Boston and Athens) and two more are in the pipeline (Vienna and Zurich). Their main activities are to hold events ranging from a simple drink to getting to know each other at more formal events, for example as speakers in STEM-related fields.

One of the most rewarding aspects of running the network has been getting to know alumni and hearing their varied stories. “It’s great that CERN values the network of physicists past and present who’ve passed through or been based at the lab. The network has already led to some very useful contacts for me,” writes former summer student Matin Durrani, now editor of Physics World magazine. “Best wishes from Guyancourt (first office) as well as from Valenciennes (second office) and of course Stręgoborzyce (my family home). Let’s grow and grow and show where we are after our experience with CERN,” writes former technical student Wojciech Jasonek, now a mechanical engineering consultant.

After two years of existence we can say that the network is firmly taking root and that the CERN Office of Alumni Relations has seen engagement and interactions between alumni growing. Anyone who has been (or still is) a user, associate, fellow, staff or student at CERN, is eligible to join the network via alumni.cern.

“From my vast repertoire …” is a rather peculiar opening to a seminar or a lecture. The late CERN theorist Guido Altarelli probably intended it ironically, but his repertoire was indeed vast, and it spanned the whole of the “famous triumph of quantum field theory,” as Sidney Coleman puts it in his classic monograph Aspects of Symmetry. There can be little doubt that a conspicuous part of this triumph must be ascribed to the depth and breadth of Altarelli’s contributions: the HERA programme at DESY, the LEP and LHC programmes at CERN, and indeed the current paradigms of the strong and electroweak interactions themselves, bear the unmistakable marks of Guido’s criticism and inspiration.

From My Vast Repertoire … is a memorial volume that encompasses the scientific and human legacies of Guido. The book consists of 18 well-assorted contributions that cover his entire scientific trajectory. His wide interests, and even his fear of an untimely death, are described with care and respect. For these reasons the efforts of the authors and editors will be appreciated not only by his friends, collaborators and fellow practitioners in the field, but also by younger scientists, who will find a timely introduction to the current trends in particle physics, from the high-energy scales of collider physics to the low-energy frontier of the neutrino masses. The various private pictures, which include a selection from his family and friends, make the presence of Guido ubiquitous even though his personality emerges more vividly in some contributions than others. Guido’s readiness to debate the relevant physics issues of his time is one of the recurring themes of this volume; the interpretation of monojets at the SPS, precision tests of the Standard Model at LEP, the determination of the strong coupling constant, and even the notion of naturalness, are just a few examples.

While lecturing at CERN in 2005, Nobel prize-winning theorist David Gross outlined some future perspectives on physics, and warned about the risk of a progressive balkanisation. The legacy of Guido stands out among the powerful antidotes against a never-ending fission into smaller subfields. He understood which problems are ripe to study and which are not, and that is why he was able to contribute to so many conceptually different areas, as this monograph clearly shows. The lesson we must draw from Guido’s achievements and his passion for science is that fundamental physics must be inclusive and diverse. Lasting progress does not come by looking along a single line of sight, but by looking all around where there are mature phenomena to be scrutinised at the appropriate moment.

Ilya Obodovskiy’s new book is the most detailed and fundamental survey of the subject of radiation safety that I have ever read.

The author assumes that while none of his readers will ever be exposed to large doses of radiation, all of them, irrespective of gender, age, financial situation, profession and habits, will be exposed to low doses throughout their lives. Therefore, he reasons, if it is not possible to get rid of radiation in small doses, it is necessary to study its effect on humans.

Obodovskiy adopts a broad approach. Addressing the problem of the narrowing of specialisations, which, he says, leads to poor mutual understanding between the different fields of science and industry, the author uses inclusive vocabulary, simultaneously quoting different units of measurement, and collecting information from atomic, molecular and nuclear physics, and biochemistry and biology. I would first, however, like to draw attention to the rather novel section ‘Quantum laws and a living cell’.

Quite a long time after the discovery of X-rays and radioactivity, the public was overwhelmed by “X-ray-mania and radio-euphoria”. But after World War II – and particularly after the Japanese vessel Fukuryū-Maru experienced the radioactive fallout from a thermonuclear explosion at Bikini Atoll – humanity got scared. The resulting radio-phobia determined today’s commonly negative attitudes towards radiation, radiation technologies and nuclear energy. In this book Obodovskiy shows that radio-phobia causes far greater harm to public health and economic development than the radiation itself.

The risks of ionising radiation can only be clarified experimentally. The author is quite right when he declares that medical experiments on human beings are ethically evil. Nevertheless, a large group of people have received small doses. An analysis of the effect of radiation on these groups can offer basic information, and the author asserts that in most cases results show that low-dose irradiation does not affect human health.

It is understandable that the greater part of the book, as for any textbook, is a kind of compilation, however, it does discuss several quite original issues. Here I will point out just one. To my knowledge, Obodovskiy is the first to draw attention to the fact that deep in the seas, oceans and lakes, the radiation background is two to four orders of magnitude lower than elsewhere on Earth. The author posits that one of the reasons for the substantially higher complexity and diversity of living organisms on land could be the higher levels of ionising radiation.

In the last chapter the author gives a detailed comparison of the various sources of danger that threaten people, such as accidents on transport, smoking, alcohol, drugs, fires, chemicals, terror and medical errors. Obodovskiy shows that the direct danger to human health from all nuclear applications in industry, power production, medicine and research is significantly lower than health hazards from every non-nuclear source of danger.

Discussions on how to organise a “world accelerator” took place at a pre-ICFA committee in New Orleans in the early 1970s. The talks went on for a long time, but nothing much came out of them. In 1978 John Adams and Leon Van Hove – the two CERN Director-Generals (DGs) at the time – agreed to build an electron–positron collider at CERN. There was worldwide support, but then there came competition from the US, worried that they might lose the edge in high-energy physics. Formal discussions about a Superconducting Supercollider (SSC) had already begun. While it was open to international contribution, Ronald Reagan’s “join it or not” approach to the SSC, and other reasons, put other countries off the project.

Yes. The W and Z bosons hadn’t yet been discovered, but there were already strong indications that they were there. Measuring the electroweak bosons in detail was the guiding force for LEP. There was also the hunt for the Higgs and the top quark, yet there was no guidance on the masses of these particles. LEP was proposed in two phases, first to sit at the Z pole and then the WW threshold. We made the straight sections as long as possible so we could increase the energy during the LEP2 phase.

The first proposal for LEP was initially refused by the CERN Council because it had a 30 km circumference and cost 1.4 billion Swiss Francs. When I was appointed DG in February 1979, they asked me to sit down with both current DGs and make a common proposal, which we did. This was the proposal with the idea to make it 22 km in circumference. At that time CERN had a “basic” programme (which all Member States had to pay for) and a “special” programme whereby additional funds were sought. The latter was how the Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR) and the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) were built. But the cost of LEP made some Member States hesitate because they were worried that it would eat too much into the resources of CERN and national projects.

After long discussions, Council said: yes, you build it, but do so within a constant budget. It seemed like an impossible task because the CERN budget had peaked before I took over and it was already in decline. I was advised by some senior colleagues to resign because it was not possible to build LEP on a constant budget. So we found another idea: make advance payments and create debts. Council said we can’t make debts with a bank, so we raided the CERN pension fund instead. They agreed happily since I had to guarantee them 6% interest, and as soon as LEP was built we started to pay it back. With the LHC, CERN had to do the same (the only difference was that Council said we could go to a bank). CERN is still operating within essentially the same constant budget today (apart from compensation for inflation), with the number of users having more than doubled – a remarkable achievement! To get LEP approved, I also had to say to Council that CERN would fund the machine and others would fund the experiments. Before LEP, it was usual for CERN to pay for experiments. We also had to stop several activities like the ISR and the BEBC bubble chamber. So LEP changed CERN completely.

It was wonderful to see the W and Z discovered at the SPS while LEP was being built. Of course, we were disappointed that the Higgs and the top were not discovered. But, look, these things just weren’t known then. When I was at DESY, we spent 5 million Deutsche Marks to increase the radio-frequency power of the PETRA collider because theorists had guaranteed that the top quark would be lighter than 25 GeV! At LEP2 it was completely unknown what it would find.

These days, there is a climate where everything that is not a peak is not a discovery. People often say “not much came out from LEP”. That is completely wrong. What people forget is that LEP changed high-energy physics from a 10% to a 1% science. Apart from establishing the existence of three neutrino flavours, the LEP experiments enabled predictions of the top-quark mass that were confirmed at Fermilab’s Tevatron. This is because LEP was measuring the radiative corrections – the essential element that shows the Standard Model is a renormalisable theory, as shown theoretically by ’t Hooft and Veltman. It also showed that the strong coupling constant, αs, runs with energy and allowed the coupling constants of all the gauge forces to be extrapolated to the Planck mass – where they do not meet. To my mind, this is the most concrete experimental evidence that the Standard Model doesn’t work, that there is something beyond it.

When LEP was conceived, the Higgs was far in the future and nobody was really talking about it. When the LEP tunnel was discussed, it was only the competition with SSC. The question was: who would win the race to go to higher energy? It was clear in the long run that the proton machine would win, so we had the famous workshop in Lausanne in 1983 where we discussed the possibility of putting a proton collider in the LEP tunnel. It was foreseen then to put it on top of LEP and to have them running at the same time. With the LHC, we couldn’t compete in energy with the SSC so we went for higher luminosities. But when we looked into this, we realised we had to make the tunnel bigger. The original proposal, as approved by Council in October 1981, had a tunnel size of 22 km and making it bigger was a big problem because of the geology – basically we couldn’t go too far under the Jura mountains. Nevertheless, I decided to go to 27 km against the advice of most colleagues and some advisory committees, a decision that delayed LEP by about a year because of the water in the tunnel. But it is almost forgotten that the LEP tunnel size was only chosen in view of the LHC.

Yes and no. One of the big differences compared to the LEP days is that, back then, the population around CERN did not know what we were doing – the policy of management was not to explain what we are doing because it is “too complicated”! I was very surprised to learn this when I arrived as DG, so we had many hundreds of meetings with the local community. There was a misunderstanding about the word “nuclear” in CERN’s name – they thought we were involved in generating nuclear power. That fortunately has completely changed and CERN is accepted in the area.

What is different concerns the physics. We are in a situation more similar to the 1970s before the famous J/ψ discovery when we had no indications from theory where to go. People were talking about all sorts of completely new ideas back then. Whatever one builds now is penetrating into unknown territory. One cannot be sure we will find something because there are no predictions of any thresholds.

In the end I think that the next machine has to be a world facility. The strange thing is that CERN formally is still a European lab. There are associates and countries who contribute in kind, which allows them to participate, but the boring things like staff salaries and electricity have to be paid for by the Member States. One therefore has to find out whether the next collider can be built under a constant budget or whether one has to change the constitutional model of CERN. In the end I think the next collider has to be a proton machine. Maybe the LEP approach of beginning with an electron–positron collider in a new tunnel would work. I wouldn’t exclude it. I don’t believe that an electron–positron linear collider would satisfy requests for a world machine as its energy will be lower than for a proton collider, and because it has just one interaction point. Whatever the next project is, it should be based on new technology such as higher field superconducting magnets, and not be just a bigger version of the LHC. Costs have gone up and I think the next collider will not fly without new technologies.

I was lucky in my career to be able to go through the whole of physics. My PhD was in optics and solid-state physics, then I later moved to nuclear and particle physics. So I’ve had this fantastic privilege. I still believe in the unity of physics in spite of all the specialisation that exists today. I am glad to have seen all of the highlights. Witnessing the discovery of parity violation while I was working in nuclear physics was one.

The future of high-energy physics is to combine with astrophysics, because the real big questions now are things like dark matter and dark energy. This has already been done in a sense. Originally the idea in particle physics was to investigate the micro-cosmos; now we find out that measuring the micro-cosmos means investigating matter under conditions that existed nanoseconds after the Big Bang. Of course, many questions remain in particle physics itself, like neutrinos, matter–antimatter inequality and the real unification of the forces.

I was advised by some senior colleagues to resign because it was not possible to build LEP on a constant budget

With LEP and the LHC, the number of outside users who build and operate the experiments increased drastically, so the physics competence now rests to a large extent with them. CERN’s competence is mainly new technology, both for experiments and accelerators. At LEP, cheap “concrete” instead of iron magnets were used to save on investment, and coupled RF cavities to use power more efficiently were invented, and later complemented by superconducting cavities. New detector technologies following the CERN tradition of Charpak turned the LEP experiments into precision ones. This line was followed by the LHC, with the first large-scale use of high-field superconducting magnets and superfluid-helium cooling technology. Whatever happens in elementary particle physics, technology will remain one of CERN’s key competences. Above and beyond elementary particle physics, CERN has become such a symbol and big success for Europe, and a model for worldwide international cooperation, that it is worth a large political effort to guarantee its long-term future.

Nearly 70 years ago, before CERN was established, two models for European collaboration in fundamental physics were on the table: one envisaged opening up national facilities to researchers from across the continent, the other the creation of a new, international research centre with world-leading facilities. Discussions were lively, until one delegate pointed out that researchers would go to wherever the best facilities were.

From that moment on, CERN became an accelerator laboratory aspiring to be at the forefront of technology to enable the best science. It was a wise decision, and one that I was reminded of while listening to the presentations at the open symposium of the European Strategy for Particle Physics in Granada, Spain, in May. Because among the conclusions of this very lively meeting was the view that providing world-leading accelerator and experimental facilities is precisely the role the community needs CERN to play today.

There was huge interest in the symposium, as witnessed by the 600-plus participants, including many from the nuclear and astroparticle physics communities. The vibrancy of the field was fully on display, with future hadron colliders offering the biggest leap in energy reach for direct searches for new physics. Precision electroweak studies at the few per cent level, particularly for the Higgs particle, will obtain sensitivities for similar mass scales. The LHC, and soon the High-Luminosity LHC, will go a long way towards achieving that goal of precision. Indeed, it’s remarkable how far the LHC experiments have come in overturning the old adage that hadrons are for discovery and leptons for precision – the LHC has established itself as a precision tool, and this is shaping the debate as to what kind of future we can expect.

Nevertheless, however precise proton–proton physics becomes, it will still fall short in some areas. To fully understand the absolute width of the Higgs, for example, a lepton machine will be needed, and no fewer than four implementations were discussed. So, one key conclusion is that if we are to cover all bases, no single facility will suffice. One way forward was presented by the chair of the Asian Committee for Future Accelerators Geoff Taylor, who advocated a lepton machine for Asia while Europe would focus on advancing the hadron frontier.

Interest in muon colliders was rekindled, not least because of some recent reconsiderations in muon cooling (CERN Courier July/August 2018 p19). The great and recent progress of plasma-wakefield accelerators, including AWAKE at CERN, calls for further research in this field so as to render the technology usable for particle physics. Methods of dark-matter searches abound and are an important element of the discussion on physics beyond colliders, using single beams at CERN.

The Granada meeting was a town meeting on physics. Yet, it is clear to all that we can’t make plans solely on the basis of the available technology and a strong physics case, but must also consider factors such as cost and societal impact in any future strategy for European particle physics. With all the available technology options and open questions in physics, there’s no doubt that the future should be bright. The European Strategy Group, however, has a monumental challenge in plotting an affordable course to propose to the CERN Council in March next year.

There were calls for CERN to diversify and lend its expertise to other areas of research, such as gravitational waves: one speaker even likened interferometers to accelerators without beams. In terms of the technologies involved, that statement stands up well to scrutiny, and it is true that technology developed for particle physics at CERN can help the advancement of other fields. CERN already formally collaborates with organisations like ITER and the ESS, sharing our innovation and expertise. However, for me, the strongest message from Granada is that it is CERN’s focus on remaining at the forefront of particle physics that has enabled the Organization to contribute to a diverse range of fields. CERN needs to remain true to that founding vision of being a world-leading centre for accelerator technology. That is the starting point. From it, all else follows.

In the mid-1970s, particle physics was hot. Quarks were in. Group theory was in. Field theory was in. And so much progress was being made that it seemed like the fundamental theory of physics might be close at hand. Right in the middle of all this was Murray Gell-Mann – responsible for not one, but most, of the leaps of intuition that had brought particle physics to where it was. There’d been other theories, but Murray’s, with their somewhat elaborate and abstract mathematics, were always the ones that seemed to carry the day.

It was the spring of 1978 and I was 18 years old. I’d been publishing papers on particle physics for a few years. I was in England, but planned to soon go to graduate school in the US, and was choosing between Caltech and Princeton. One weekend afternoon, the phone rang. “This is Murray Gell-Mann”, the caller said, then launched into a monologue about why Caltech was the centre of the universe for particle physics at the time. Perhaps not as star-struck as I should have been, I asked a few practical questions, which Murray dismissed. The call ended with something like, “Well, we’d like to have you at Caltech”.

I remember the evening I arrived, wandering around the empty fourth floor of Lauritsen Lab – the centre of Caltech theoretical particle physics. There were all sorts of names I recognised on office doors, and there were two offices that were obviously the largest: “M. Gell-Mann” and “R. Feynman”. In between them was a small office labelled “H. Tuck”, which by the next day I’d realised was occupied by the older but very lively departmental assistant.

I never worked directly with Murray but I interacted with him frequently while I was at Caltech. He was a strange mixture of gracious and gregarious, together with austere and combative. He had an expressive face, which would wrinkle up if he didn’t approve of what was being said. Murray always grouped people and things he approved of, and those he didn’t – to which he would often give disparaging nicknames. (He would always refer to solid- state physics as “squalid-state physics”.) Sometimes he would pretend that things he did not like simply did not exist. I remember once talking to him about something in quantum field theory called the beta function. His face showed no recognition of what I was talking about, and I was getting slightly exasperated. Eventually I blurted out, “But, Murray, didn’t you invent this?” “Oh”, he said, suddenly much more charming, “You mean g times the psi function. Why didn’t you just say that? Now I understand.”

I could never quite figure out what it was that made Murray impressed by some people and not others. He would routinely disparage physicists who were destined for great success, and would vigorously promote ones who didn’t seem so promising, and didn’t in fact do well. So when he promoted me, I was on the one hand flattered, but on the other hand concerned about what his endorsement might really mean.

The interaction between Murray Gell-Mann and Richard Feynman was an interesting thing to behold. Both came from New York, but Feynman relished his “working class” New York accent while Gell-Mann affected the best pronunciation of words from any language. Both would make surprisingly childish comments about the other. I remember Feynman insisting on telling me the story of the origin of the word “quark”. He said he’d been talking to Murray one Friday about these hypothetical particles, and in their conversation they’d needed a name for them. Feynman told me he said (no doubt in his characteristic accent), “Let’s call them ‘quacks’”. The next Monday, he said, Murray came to him very excited and said he’d found the word “quark” in a novel by James Joyce. In telling this to me, Feynman then went into a long diatribe about how Murray always seemed to think the names for things were so important. “Having a name for something doesn’t tell you a damned thing,” Feynman said. Feynman went on, mocking Murray’s concern for things like what different birds are called. (Murray was an avid bird watcher.) Meanwhile, Feynman had worked on particles that seemed (and turned out to be) related to quarks. Feynman had called them “partons”. Murray insisted on always referring to them as “put-ons”.

He was a strange mixture of gracious and gregarious

Even though in terms of longstanding contributions to particle physics, Murray was the clear winner, he always seemed to feel as if he was in the shadow of Feynman, particularly with Feynman’s showmanship. When Feynman died, Murray wrote a rather snarky obituary, saying of Feynman: “He surrounded himself with a cloud of myth, and he spent a great deal of time and energy generating anecdotes about himself.” I never quite understood why Murray – who could have gone to any university in the world – chose to work at Caltech for 33 years in an office two doors down from Feynman.

Murray cared a lot about what people thought of him, but wasn’t particularly good at reading other people. Yet, alongside the brush-offs and the strangeness, he could be personally very gracious. I remember him inviting me several times to his house. He also did me quite a few favours in my career. I don’t know if I would call Murray a friend, though, for example, after his wife Margaret died, he and I would sometimes have dinner together, at random restaurants around Pasadena. It wasn’t so much that I felt of a different generation from him (which of course I was). It was more that he exuded a certain aloof tension, that made one not feel very sure about what the relationship really was.

Murray Gell-Mann had an amazing run. For 20 years he had made a series of bold conjectures about how nature might work – strangeness, V-A theory, SU(3), quarks, QCD – and in each case he had been correct, while others had been wrong. He had one of the more remarkable records of repeated correct intuition in the whole history of science.

He tried to go on. He talked about “grand unification being in the air”, and (along with many other physicists) discussed the possibility that QCD and the theory of weak interactions might be unified in models based on groups such as SU(5) and SO(10). He considered supersymmetry. But quick validations of these theories didn’t work out, though even now it’s still conceivable that some version of them might be correct.

I have often used Murray as an example of the challenges of managing the arc of a great career. From his twenties to his forties, Murray had the golden touch. His particular way of thinking had success after success, and in many ways he defined physics for a generation. By the time I knew him, the easy successes were over. Perhaps it was Murray; more likely, it was just that the easy pickings from his approach were now gone. He so wanted to succeed as he had before, not just in physics but in other fields and endeavours. But he never found a way to do it – and always bore the burden of his early success.

Though Murray is now gone, the physics he discovered will live on, defining an important chapter in the quest for our understanding of the fundamental structure of our universe.

• This article draws on a longer tribute published on www.stephenwolfram.com.

In April 1960, Prince Philip, husband of Queen Elizabeth II, piloted his Heron airplane to Geneva for an informal visit to CERN. Having toured the laboratory’s brand new “25 GeV” Proton Synchrotron (PS), he turned to his host, president of the CERN Council François de Rose, and struck at the heart of fundamental exploration: “What have you got in mind for the future? Having built this machine, what next?” he asked. De Rose replied that this was a big problem for the field: “We do not really know whether we are going to discover anything new by going beyond 25 GeV,” he said. Unbeknown to de Rose and everyone else at that time, the weak gauge bosons and other phenomena that would transform particle physics were lying not too far above the energy of the PS.

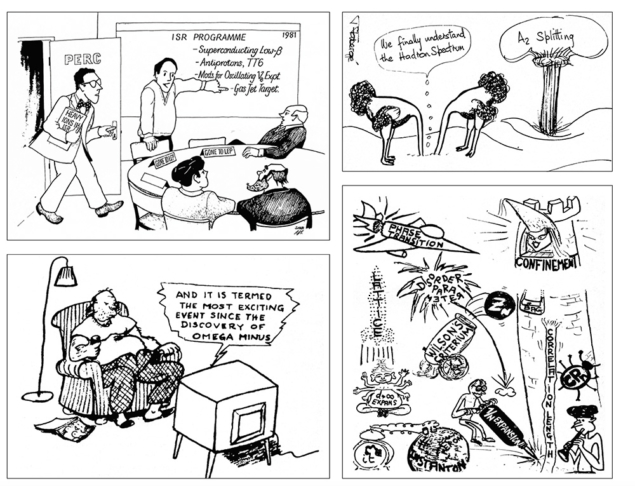

This is a story repeated in elementary particle physics, and which CERN Courier, celebrating its 60th anniversary this summer, offers a bite-sized glimpse of.

The first issue of the Courier was published in August 1959, just a few months before the PS switched on, at a time when accelerators were taking off. The PS was the first major European machine, quickly reaching an energy of 28 GeV, only to be surpassed the following year by Brookhaven’s Alternating Gradient Synchrotron. The March 1960 issue of the Courier described a meeting at CERN where 245 scientists from 28 countries had discussed “a dozen machines now being designed or constructed”. Even plasma-based acceleration techniques – including a “plasma betatron” at CERN – were on the table.

The picture is not so different today (see Granada symposium thinks big), though admittedly thinner on projects under construction. Some things remain eerily pertinent: swap “25 GeV” for “13 TeV” in de Rose’s response to Prince Philip, and his answer still stands with respect to what lies beyond the LHC’s energy. Other things are of a time gone by. The third issue of the Courier, in October 1959, proudly declared that “elementary particles number 32” (by 1966 that number had grown to more than 50 – see “Not so elementary”). Another early issue likened the 120 million Swiss Franc cost of the PS to “10 cigarettes for each of the 220 million inhabitants of CERN’s 12 Member States”.

The general situation of elementary particle physics back then, argued the August 1962 issue, could be likened to atomic physics in 1924 before the development of quantum mechanics. Summarising the 1962 ICHEP conference held at CERN, which attracted an impressive 450 physicists from 158 labs in 39 countries, the leader of the CERN theory division Léon Van Hove wrote: “The very fact that the variety of unexpected findings is so puzzling is a promise that new fundamental discoveries may well be in store at the end of a long process of elucidation.” Van Hove was right, and the 1960s brought the quark model and electroweak theory, laying a path to the Standard Model. Not that this paradigm shift is much apparent when flicking through issues of the Courier from the period; only hindsight can produce the neat logical history that most physics students learn.

Within a few years of PS operations, attention soon turned to a machine for the 1970s. A report on the 24th session of the CERN Council in the July 1963 issue noted ECFA’s recommendation that high priority be given to the construction in Europe of two projects: a pair of intersecting storage rings (ISR, which would become the world’s first hadron collider) and a new proton accelerator of a very high energy “probably around 300 GeV”, which would be 10 times the size of the PS (and eventually renamed the Super Proton Synchrotron, SPS). Mervyn Hine of the CERN directorate for applied physics outlined in the August 1964 issue how this so-called “Summit program” should be financed. He estimated the total annual cost (including that of the assumed national programmes) to be about 1100 million Swiss Francs by 1973, concluding that this was in step with a minimum growth for total European science. He wrote boldly: “The scientific case for Europe’s continuing forcefully in high-energy physics is overwhelming; the equipment needed is technically feasible; the scientific manpower needed will be available; the money is trivial. Only conservatism or timidity will stop it.”

Similar sentiments exist now in view of a post-LHC collider. There is also nothing new, as the field grows ever larger in scale, in attacks on high-energy physics from outside. In an open letter published in the Courier in April 1964, nuclear physicist Alvin Weinberg argued that the field had become “remote” and that few other branches of science were “waiting breathlessly” for insights from high-energy physics without which they could not progress. Director-General Viki Weisskopf, writing in April 1965, concluded that the development of science had arrived at a critical stage: “We are facing today a situation where it is threatened that all this promising research will be slowed down by constrained financial support of high-energy physics.”

Deciding where to build the next collider and getting international partners on board was also no easier in the past, if the SPS was any guide. The September 1970 issue wrote that the “present impasse in the 300 GeV project” is due to the difficulty of selecting a site and: “At the same time it is disturbing to the traditional unity of CERN that only half the Member States (Austria, Belgium, Federal Republic of Germany, France, Italy and Switzerland) have so far adopted a positive attitude towards the project.” That half-a-century later, the SPS, soon afterwards chosen to be built at CERN, would be feeding protons into a 27 km-circumference hadron collider with a centre-of-mass energy of 13 TeV was unthinkable.

An editorial in the January/February 1990 issue of the Courier titled “Diary of a dramatic decade” summed up a crucial period that had the Large Electron Positron (LEP) collider at its centre: Back in 1980, it said, the US was the “mecca” of high-energy physics. “But at CERN, the vision of Carlo Rubbia, the invention of new beam ‘cooling’ techniques by Simon van der Meer, and bold decisions under the joint Director-Generalship of John Adams and Léon Van Hove had led to preparations for a totally new research assault – a high-energy proton–antiproton collider.” The 1983 discoveries of the W and Z bosons had, it continued, “nudged the centroid of particle physics towards Europe,” and, with LEP and also HERA at DESY operating, Europe was “casting off the final shackles of its war-torn past”.

Despite involving what at that time was Europe’s largest civil-engineering project, LEP didn’t appear to attract much public attention. It was planned to be built within a constant CERN budget, but there were doubts as to whether this was possible (see Lessons from LEP). The September 1983 issue reported on an ECFA statement noting that reductions in CERN’s budget had put is research programme under “severe stress”, impairing the lab’s ability to capitalise on its successful proton–antiproton programme. “The European Laboratories have demonstrated their capacity to lead the world in this field, but the downward trend of support both for CERN and in the Member States puts this at serious risk,” it concluded. At the same time, following a famous meeting in Lausanne, the ECFA report noted that proton–proton collision energies of the order of 20 TeV could be reached with superconducting magnets in the LEP tunnel and “recommends that this possibility be investigated”.

Physicists were surprisingly optimistic about the possibility of such a large hadron collider. In the October 1981 issue, Abdus Salam wrote: “In the next decade, one may envisage the possible installation of a pp̅ collider in the LEP tunnel and the construction of a supertevatron… But what will happen to the subject 25 years from now?” he asked. “Accelerators may become as extinct as dinosaurs unless our community takes heed now and invests efforts on new designs.” Almost 40 years later, the laser-based acceleration schemes that Salam wrote of, and others, such as muon colliders, are still being discussed.

Accelerator physicist Lee Teng, in an eight-page long report about the 11th International Conference on High Energy Accelerators in the September 1980 issue, pointed out that seven decades in energy had been mastered in 50 years of accelerator construction. Extrapolating to the 21st century, he envisaged “a 20 TeV proton synchrotron and 350 GeV electron–positron linear colliders”. On CERN’s 50th anniversary in September 2004, former Director-General Luciano Maiani predicted what the post-2020 future might look like, asserting that “a big circular tunnel, such as that required by a Very Large Hadron Collider, would have to go below Lake Geneva or below the Jura (or both). Either option would be simply too expensive to consider. This is why a 3–5 TeV Compact Linear Collider (CLIC) would be the project of choice for the CERN site.” It is the kind of decision that the current CERN management is weighing up today, 15 years later.

This collider-centric view of 60 years of CERN Courier does little justice to the rest of the magazine’s coverage of fixed-target physics, neutrino physics, cosmology and astrophysics, detector and accelerator physics, computing, applications, and broader trends in the field. It is striking how much the field has advanced and specialised. Equally, it is heartening to find so many parallels with today. Some are sociological: in October 1995 a report on an ECFA study noted “much dissatisfaction” with long author lists and practical concerns about the size of the even bigger LHC-experiment collaborations over the horizon. Others are more strategic.

It is remarkable to read through back issues of the Courier from the mid-1970s to find predictions for the masses of the W and Z bosons that turned out to be correct to within 15%. This drove the success of the Spp̅S and LEP programmes and led naturally to the LHC – the collider to hunt down the final piece of the electroweak jigsaw, the “so-called Higgs mesons” as a 1977 issue of the Courier put it. Following the extraordinary episode that was the development and completion of the Standard Model, we find ourselves in a similar position as we were in the PS days regarding what lies over the energy frontier. Looking back at six decades of fundamental exploration as seen through the imperfect lens of this magazine, it would take a bold soul to claim that it isn’t worth a look.

Murray Gell-Mann’s scientific career began at the age of 15, when he received a scholarship from Yale University that allowed him to study physics. Afterwards he went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and worked under Victor Weisskopf. He completed his PhD in 1951, at the age of 21, and became a postdoc at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.

The following year, Gell-Mann joined the research group of Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago. He was particularly interested in the new particles that had been discovered in cosmic rays, such as the six hyperons and the four K-mesons. Nobody understood why these particles were created easily in collisions of nucleons, yet decayed rather slowly. To understand the peculiar properties of the new hadrons, Gell-Mann introduced a quantum number, which he called strangeness (S): nucleons were assigned S = 0; the Λ hyperon and the three Σ hyperons were assigned S = (–1); the two Ξ hyperons had S = (–2); and the negatively charged K-meson had S = (–1).

Gell-Mann assumed that the strangeness quantum number is conserved in the strong and electromagnetic interactions, but violated in the weak interactions. The decays of the strange particles into particles without strangeness could only proceed via the weak interaction.

The idea of strangeness thus explained, in a simple way, the production and decay rates of the newly discovered hadrons. A new particle with S = (–1) could be produced by the strong interaction together with a particle with S = (+1) – e.g. a negatively charged Σ can be produced together with a positively charged K meson. However, a positively charged Σ could not be produced together with a negatively charged K meson, since both particles have S = (–1).

In 1954 Gell-Mann and Francis Low published details of the renormalisation of quantum electrodynamics (QED). They had introduced a new method called the renormalisation group, which Kenneth Wilson (a former student of Gell-Mann) later used to describe the phase transitions in condensed-matter physics. Specifically, Gell-Mann and Low calculated the energy dependence of the renormalised coupling constant. In QED the effective coupling constant increases with the energy. This was measured at the LEP collider at CERN, and found to agree with the theoretical prediction.

In 1955 Gell-Mann went to Caltech in Pasadena, on the invitation of Richard Feynman, and was quickly promoted to full professor – the youngest in Caltech’s history. In 1957, Gell-Mann started to work with Feynman on a new theory of the weak interaction in terms of a universal Fermi interaction given by the product of two currents and the Fermi constant. These currents were both vector currents and axial-vector currents, and the lepton current is a product of a charged lepton field and an antineutrino field. The “V–A” theory showed that since the electrons emitted in a beta-decay are left-handed, the emitted antineutrinos are right-handed – thus parity is not a conserved quantum number. Some experiments were in disagreement with the new theory. Feynman and Gell-Mann suggested in their paper that these experiments were wrong, and it turned out that this was the case.

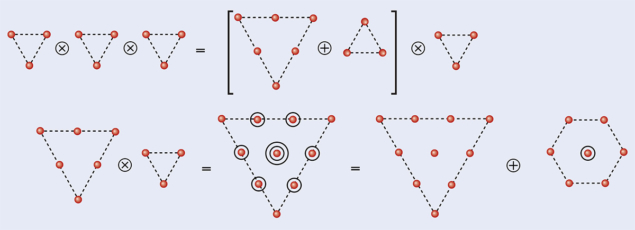

In 1960 Gell-Mann invented a new symmetry to describe the new baryons and mesons found in cosmic rays and in various accelerator experiments. He used the unitary group SU(3), which is an extension of the isospin symmetry based on the group SU(2). The two nucleons and the six hyperons are described by an octet representation of SU(3), as are the eight mesons. Gell-Mann often described the SU(3)-symmetry as the “eightfold way” in reference to the eightfold path of Buddhism. At that time, it was known that there exist four Δ resonances, three Σ resonances and two χ resonances. There is no SU(3)-representation with nine members, but there is a decuplet representation with 10 members. Gell-Mann predicted the existence and the mass of a negatively charged 10th particle with strangeness S = (–3), which he called the Ω particle.

The Ω is unique in the decuplet: due to its strangeness it could only decay by the weak interaction, and so would have a relatively long lifetime. This particle was discovered in 1964 by Nicholas Samios and his group at Brookhaven National Laboratory, at the mass Gell-Mann had predicted. The SU(3) symmetry was very successful and in 1969 Gell-Mann received the Nobel Prize in Physics “for his contributions and discoveries concerning the classification of elementary particles and their interactions.”

In 1962 Gell-Mann proposed the algebra of currents, which led to many sum rules for cross sections, such as the Adler sum rule. Current algebra was the main topic of research in the following years and Gell-Mann wrote several papers with his colleague Roger Dashen on the topic.

In 1964 Gell-Mann discussed the triplets of SU(3), which he called “quarks”. He proposed that quarks were the constituents of baryons and mesons, with fractional electric charges, and published his results in Physics Letters. Feynman’s former PhD student George Zweig, who was working at CERN, independently made the same proposal. But the quark model was not considered seriously by many physicists. For example, the Ω is a bound state of three strange quarks placed symmetrically in an s-wave, which violated the Pauli principle since it was not anti-symmetric. In 1968, quarks were found indirectly in deep-inelastic electron–proton experiments performed at SLAC.

By then it had been proposed, by Oscar Greenberg and by Moo-Young Han and Yoichiro Nambu, that quarks possess additional properties that keep the Pauli principle intact. By imagining the quarks in three “colours” – which later came to be called red, green and blue – hadrons could be considered as colour singlets, the simplest being the bound states of a quark and an antiquark (meson) or of three quarks (baryon). Since baryon wave functions are antisymmetric in the colour index, there is no problem with the Pauli principle. Taking the colour quantum number as a gauge quantum number, like the electric charge in QED, yields a gauge theory of the strong interactions: colour symmetry is an exact symmetry and the gauge bosons are massless gluons, which transform as an octet of the colour group. Nambu and Han had essentially arrived at quantum chromodynamics (QCD), but in their model the quarks carried integer electrical charges.

The quark model was not considered seriously by many physicists

I was introduced to Gell-Mann by Ken Wilson in 1970 at the Aspen Center of Physics, and we worked together for a period. In 1972 we wrote down a model in which the quarks had fractional charges, proposing that, since only colour singlets occur in the spectrum, fractionally charged quarks remain unobserved. The discovery in 1973 by David Gross, David Politzer and Frank Wilczek that the self-interaction of the gluons leads to asymptotic freedom – whereby the gauge coupling constant of QCD decreases if the energy is increased – showed that quarks are forever confined. It was rewarded with the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physics, although a rigorous proof of quark confinement is still missing.

Gell-Mann did not just contribute to the physics of strong interactions. In 1979, along with Pierre Ramond and Richard Slansky, he wrote a paper discussing details of the “seesaw mechanism” – a theoretical proposal to account for the very small values of the neutrino masses introduced a couple of years earlier. After 1980 he also became interested in string theory. His wide-ranging interests in languages, and other areas beyond physics are also well documented.

I enjoyed working with Murray Gell-Mann. We had similar interests in physics, and we worked together until 1976 when I left Caltech and went to CERN. He visited often. In May 2019, during a trip to Los Alamos Laboratory, I was fortunate to have had the chance to visit Murray at his house in Santa Fe one last time.

Further memories of Gell-Mann can be found at Gell-Mann’s multi-dimensional genius and Memories from Caltech.

One of the 20th century’s most amazing brains has stopped working. Nobel laureate Murray Gell-Mann died on 24 May at the age of 89. It is impossible to write a complete obituary of him, since he had so many dimensions that some will always be forgotten or neglected.

Murray was the leading particle theorist in the 1950s and 1960s in a field that had attracted the brightest young stars of the post-war generation. But he was also a polyglot who could tell you any noun in at least 25 languages, a walking encyclopaedia, a nature lover and a protector of endangered species, who knew all the flowers and birds. He was an early environmentalist, but he was so much more. It has been one of the biggest privileges in my life to have worked with him and to have been a close friend of his.

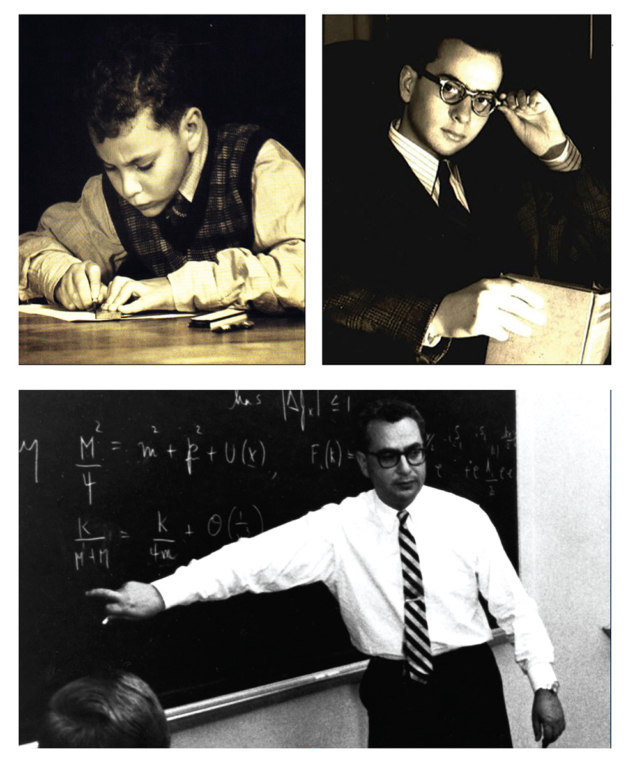

Murray Gell-Mann was born into a Jewish immigrant family in New York six weeks before the stock-market crash of October 1929. He was a trailing child, with a brother who was nine years older and relatively aged parents. He used to joke that he had been born by accident. His father had failed his studies and, after Murray’s birth, worked as a guard in a bank vault. Murray was never particularly close to father, but often talked about him.

According to family legend, the first words that Murray spoke were “The lights of Babylon”, when he was looking at the night sky over New York at the age of two. At three, he could read and multiply large numbers in his head. At five he could correct older people about their language and in discussions. His interest for numismatics had already begun: when a friend of the family showed him what he claimed was a coin from Emperor Tiberius’ time, Murray corrected the pronunciation and said it was not from that time. At the age of seven, he participated in – and won – a major annual spelling competition in New York for students up to the age of 12. The last word that only he could spell and explain was “subpoena”, also citing its Latin origins and correcting the pronunciation of the moderator.

By the age of nine he had essentially memorised the Encyclopaedia Britannica. The task sounds impossible, but some of us did a test behind his back once in the 1970s. The late Myron Bander had learnt and studied an incomprehensible word and steered the discussion on to it over lunch. Of course Murray knew what the word was. He even recalled the previous and subsequent entries on the page.

Murray’s parents didn’t know what to do with him, but his piano teacher (music was not his strong side) made them apply for a scholarship so that he could start at a good private school. He was three years younger than his classmates, yet they always looked to him to see if he approved of what the teachers said. His tests were faultless, except for the odd exception. Once he came home and had scored “only” 97%, to which his father said: How could you miss this? His brother, who was more “normal”, was a great nature lover and became a nature photographer and later a journalist. He taught Murray about birds and plants, which would become a lifelong passion.

At the age of 15, he finished high school and went to Yale. He did not know which subject he would choose as a major, since he was interested in so many subjects. It became physics, partly to please his father who had insisted on engineering such that he could get a good job. He then went to MIT for his doctoral studies, receiving the legendary Victor “Viki” Weisskopf as his advisor. Murray wanted to do something pioneering, but he didn’t succeed. He tried for a whole semester and at the same time studied Chinese and learnt enough characters to read texts. He finally decided to present a thesis in nuclear physics, which was approved but that he never wanted to talk about. When Weisskopf, later in life, was asked what his biggest contribution to physics was, he answered: “Murray Gell-Mann”.

At the age of 21 Murray was ready to fly and went to the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) as one of Robert Oppenheimer’s young geniuses. In the next year he went to the University of Chicago under Enrico Fermi, first as an instructor and in a few years became an associate professor. Even though he had not yet produced outstanding work, when he came to Chicago he was branded as a genius. At the IAS he had started to work on particle physics. He collaborated with Francis Low on renormalisation and realised that the coupling constant in a renormalisable quantum field theory runs with energy. As would happen so often, he procrastinated with the publication until 1954, by which time Petermann and Stückelberg had published this result.

This was during the aftermath of QED and Gell-Mann wanted to attack the strong interactions. He started his odyssey to classify all the new particles and introduced the concept of “strangeness” to specify the kaons and the corresponding baryons. This was also done independently by Kazuhiko Nishijima. When he was back at the IAS in 1955, Murray solved the problem with KL and Ks, the two decay modes of the neutral kaons in modern language (better known as the τ–θ puzzle). According to him, he showed this to Abraham Pais who said, “Why don’t we publish it?”, which they did. They were never friends after that. Murray also once told me that this was the hardest problem that he had solved.

Aged 26, he lectured at Caltech on his renormalisation and kaon work. Richard Feynman, who was the greatest physicist at the time, said that he thought he knew everything, but these things he did not know. Feynman immediately said that Murray had to come to Caltech and dragged him to the dean. A few weeks later, he was a full professor. A large cavalcade of new results began to come out. Because he had difficulty relinquishing his works, they numbered just a few a year. But they were like cathedrals, with so many new details that he came to dominate modern particle physics.

After the ground-breaking work of T D Lee and C N Yang on parity violation in the weak interactions, Gell-Mann started to work on a dynamical theory – as did Feynman. In the end the dean of the faculty forced them to publish together, and the V–A theory was born. George Sudarshan and Robert Marshak also published the same result, and there was a long-lasting fight about who had told who before. Murray’s part of the paper, which is the second half, is also a first sketch of the Standard Model, and every sentence is worth reading carefully. It takes students of exegetics to unveil all the glory of Murray’s texts. Murray was to physics writing what Joseph Conrad was to novel writing!

Sometimes there are people born with all the neurons in the right place

Murray then turned back to the strong interactions and, with Maurice Lévy, developed the non-linear sigma model for pion physics to formulate the partially conserved axial vector current (PCAC). This was published within days of Yoichiro Nambu’s ground-breaking paper where he understood pion physics and PCAC in terms of spontaneous breaking of the chiral symmetry. In a note added to the proof they introduced a “funny” angle to describe the decay of 14O, which a few years later became the Cabibbo angle in Nicola Cabibbo’s universal treatment of the weak interactions.

Gell-Mann then made the great breakthrough when he classified the strongly interacting particles in terms of families of SU(3), a discovery also made by Yuval Ne’eman. The paper was never published in a journal and he used to joke that one day he would find out who rejected it. With this scheme he could predict the existence of the triply strange Ω– baryon, which was discovered in 1964 right where he predicted it would be. It paved the way for Gell-Mann’s suggestion in 1963 that all the baryons were made up of three fundamental particles, which in the published form he came to call quarks, after a line in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, “three quarks for Muster Mark”. The same idea was also put forward by George Zweig who called them “aces”. It was a very difficult thing for Murray to propose such a wild idea, and he formulated it extremely carefully to leave all doors open. Again, his father’s approval loomed in the background.

With the introduction of current algebra he had laid the ground for the explosion in particle theory during the 1970s. In 1966, Weisskopf’s 60th birthday was celebrated, and somehow Murray failed to show up. When he later received the proceedings, he was so ashamed that he did not open it. Had he done so, he would have found Nambu’s suggestion of a non-abelian gauge field theory with coloured quarks for the strong interactions. Nambu did not like fractional charges so he had given the quarks integer charges. Murray later said that, had he read this paper, he would have been able to formulate QCD rather quickly.

When, at the age of 40 in 1969, he received the Nobel Prize in Physics as the sole recipient, he had been a heavily nominated candidate for the previous decade. Next year the Nobel archives for this period will be open, and scholars can study the material leading up to the prize. Unfortunately, his father had died a few weeks before the prize announcement. Murray once said to me, “If my father had lived two weeks longer, my life would have been different.”

During the 1950s and 1960s Gell-Mann had often been described in the press as the world’s most intelligent man. With a Nobel Prize in his pocket, the attraction to sit on various boards and committees became too strong to resist. His commitment to conserving endangered species also took up more of his time. Murray had also become a great collector of pre-Columbian artefacts and these were often expensive and difficult to obtain.

In the 1970s, he was displaced from the throne by people from the next generation. Murray was still the one invited to give the closing lectures at major conferences, but his own research started to suffer somewhat. In the mid-1970s, I came to Caltech as a young postdoctoral fellow. I had met him in a group before, but trembled like an aspen leaf when I first met him there. He had, of course, found out from where in Sweden I came and pronounced my name just right, and demanded that everyone else in the group do so. Pierre Ramond also arrived as a postdoc at that time, having been convinced by Murray to leave his position at Yale. After a few months we started to work together on supergravity. We did the long calculations, since Murray was often away. But he always contributed and could spot any weak links in our work immediately. Once, when we were in the middle of solving a problem after a period of several days, he came in and looked at what we did and wrote the answer on the board. Two days later we came to exactly that result. John Schwarz, who was a world champion in such calculations, was impressed and humbled.

When I left Caltech I got a carte blanche from Murray to return as often as I wanted, during which I worked with Schwarz and Michael Green developing string theory. Murray was always very positive about our work, which few others were. It was entirely thanks to him that we could develop the theory. Eventually, I couldn’t go to the US quite as often. Murray had also lost his wife in the early 1980s and never really recovered from this. In the mid-1980s he got the chance to set up a new institute in Santa Fe, which became completely interdisciplinary. He loved nature in New Mexico and here he could work on the issues that he now preferred, such as linguistics and large-scale order in nature. He dropped particle physics but was always interested in what happened in the field. Edward Witten had taken over the leadership of fundamental physics and Murray could not compete there.

Being considered the world’s most intelligent person did not make Murray very happy. He had trouble finding real friends among his peers. They were simply afraid of him. I often saw people looking away. The post-war research world is a single great world championship. For us who were younger, it was so obvious that he was intellectually superior to us that we were not disturbed by it. All the time, though, the shadow of his father was sitting on his shoulder, which led him too often to show off when he did not need to.

Sometimes people are born with all the neurons in the right place. We sometimes hear about the telephone-directory geniuses or people who know railway schedules by heart, but who otherwise are intellectually normal, if not rather weak. The fact that a few of them every century also get the neurons to make them intellectually superior is amazing. Among all Nobel laureates in physics, Murray Gell-Mann stands out. Others have perhaps done just as much in their research in physics and may be remembered longer, but I do not think that anyone had such a breadth in their knowledge. John von Neumann, the Hungarian–American mathematician who, among other things, was the first to construct a computer was another such universal genius. He could show off knowing Goethe by heart and on his death bed he cited the first sentence on each page of Faust for his brother. Murray was certainly a pain for American linguists, as he could say so many words in so many languages that he could always gain control over a discussion.

There are so many more stories that I could tell. Once he told me “Just think what I could have done if I had worked more with physics.” His almost crazy interest in so many areas took a lot of time away from physics. But he will still be remembered, I hope, as one of the great geniuses of the 20th century.