In the spring of 1960, CERN’s new proton synchrotron was delivering its first beams. In the middle of this critical phase for European particle physics, the death of CERN’s director-general, Cornelis Bakker, in an aeroplane accident was a severe blow. Although CERN’s governing Council acted swiftly by appointing John Adams to the post of acting director-general, this step necessarily prolonged the period that, in retrospect, may be characterized by the dominance of brilliant accelerator scientists.

At the same Council meeting in June 1960 that confirmed the appointment of Adams, the “modern” structure of research committees with at least as many members from outside as inside the laboratory was also approved, and the search for a definite successor for Bakker was initiated.

In any case, Adams would have to leave CERN to take up an important position in Great Britain. The discussion centred around two eminent scientists – Hendrik B G Casimir and Victor F Weisskopf. The latter was already well known at CERN, having worked in the Theory Division for a year in 1957-1958. However, when first approached, he doubted his talents for such a position – with characteristic modesty – but he expressed his willingness to act as a director of research. Casimir, for his part, made it clear that his position with Philips would make it very difficult to free himself to take over the post of director-general of CERN.

In the course of the following months, a formal nomination procedure of candidates in the Scientific Policy Committee (where Weisskopf was formally proposed by Greece), extensive deliberations and successful persuasion led to Weisskopf’s election by the Council (8 December 1960). The period of his term was first envisaged to run from 1 August 1961 to 31 July 1963, which was later extended to 31 December 1965. It can be said, without exaggeration, that in that period and under Weisskopf’s guidance the future of CERN was shaped for many years to come.

Why was CERN so fortunate to be led by precisely a personality like Weisskopf at precisely this time? The difficult situation for the laboratory, whose harmonious development had been interrupted at a critical point in its evolution, needed the special abilities of its director-general. Every fast-developing scientific organization must deal with the danger that its very size makes on its scientific aims. Scientists with little inclination towards administrative matters have to become subject to administrative and bureaucratic rules. This is even truer for an international organization.

The selection of collaborators and the future style of work is determined at the stage of most rapid initial growth, because the natural inertia of a structure made up of human beings makes it extremely difficult later on to rectify earlier mistakes. Just one number may serve as an illustration: at the end of 1960 the number of CERN staff and visiting scientists was 1166, rising to no fewer than 2530 at the time of Weisskopf’s departure in 1965.

Therefore, at this time in the history of CERN, even more than at any other, the director-general had to be a physicist who once and for all set the direction of the laboratory towards an absolute priority of science. To achieve this he had to rely on the authority of an acknowledged high reputation in his field, together with an ability to deal effectively with the administrative and organizational needs of a rapidly growing organization. In addition, CERN was placed in the delicate position of having to restore European research parity with that of the US, profiting as much as possible from the experience gained already in US, while retaining or creating at the same time the dominantly European character of the new organization.

Distinguished career

Born in Vienna in 1908, Weisskopf followed a truly cosmopolitan scientific career as a theoretical nuclear physicist, working with the most important founding fathers of modern quantum theory, contributing important results himself. Thus he was not only familiar with Germany (collaboration with Heisenberg), with Switzerland (collaboration with Pauli) and with the Nordic countries (collaboration with Niels Bohr in Copenhagen) from extended stays in the respective countries, but also with Russia (work with Landau in Kharkov), eventually accepting a position at Rochester, US, in 1937.

His qualities as a leader of a technological project in which theoretical physics only played an auxiliary role was exploited in the Manhattan Project (Los Alamos) towards the end of the Second World War. The dominantly European background of many of his collaborators was excellent preparation for the task of leading a European laboratory. Even pursuing the same scientific goal, the individual style of scientists differs greatly, the more so if those differences are amplified by distinct national backgrounds.

After the war, as professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Weisskopf soon resumed contact with Europe, which was slowly recovering from the dark years. Besides his outstanding qualifications as a theoretical physicist and as a leader of scientific enterprises, Weisskopf possessed a special quality as a physicist that physics in Europe is lacking to a large degree. Possibly because of the general structure of secondary education in Europe, mathematics plays an extremely important role in theoretical physics. Hence theoretical physics frequently becomes almost a mathematical discipline with the physical ideas submerged by an overemphasized mathematical formalism. Among experimentalists this very often causes a spectrum of emotions ranging from uncertainty to refusal, as far as the judgement of theoretical ideas is concerned.

In the US only a handful of gifted physicists knew how to bridge this gap. In my opinion Weisskopf was a master of this. Before coming to CERN, he had already taught a generation of nuclear physicists how to pick out the essential physical ideas that are always very transparent and simple (once they have been understood), but which may be hidden under many layers of mathematical formalism. Of course, the true masters of mathematical physics always knew how to isolate the physical content of complicated mathematical arguments, but the great majority of theoreticians in Europe, to this very day, unfortunately, are sometimes over-fascinated by the mathematical aspects of the physical description of nature.

The understanding of physical phenomena very often does not even require the use of precise formulae. Students at MIT had invented the notion of the “Weisskopfian”, which naturally takes care of numerical factors such ±1, i, 2π, etc. Moreover, in the book Theoretical Nuclear Physics by John M Blatt and Weisskopf, which remains a standard textbook to this day, the emphasis on simple, physically transparent arguments by Weisskopf and the more precise, but more formal presentation topics by his co-author are clearly discernible.

From MIT to CERN

To facilitate the transition from MIT to CERN, and to make optimal use of his whole period as director-general of CERN, Weisskopf became a part-time member of the CERN directorate in September 1960, dividing his time equally between MIT and CERN. Unfortunately during this transition period, in February 1961, he was involved in a traffic accident. His treatment required complicated hip surgery and a long stay in hospital. At the start of his term as director-general and less so during a large part of his stay in Geneva, Weisskopf was hampered in his freedom of movement. I vividly remember his tall figure walking with crutches through the corridors and obviously suffering pain, but never losing his friendly disposition.

The first progress report to CERN Council in December 1961 clearly reflects the situation of CERN at the beginning of the Weisskopf era. Two years after the first beam at the proton synchrotron, breakdowns and construction work on beams had prevented a completely satisfactory use of this machine, whereas the smaller synchrocyclotron was working very well. As research director, Gilberto Bernardini very aptly remarked that European researchers with a nuclear physics background had had little difficulty orienting their work towards the synchrocyclotron. The proton synchrotron, on the other hand, was a novelty for physicists, so certain mistakes had been made, particularly owing to insufficient time for the preparation of experiments.

Nevertheless, 1961 was the first year with a vigorous research programme at CERN. Not surprisingly, organizational problems and difficulties in the management of relations with universities in the member states became acute. It was recognized that at least track chamber experiments required the collaboration with institutes outside CERN for the scanning, measuring and evaluation of data. For electronic experiments, such a need was not yet seen.

The construction of the 2 m bubble chamber was continuing well, but experimental work was still done on the basis of data from the tiny 30 cm chamber and with the 81 cm Saclay chamber. The heavy-liquid chamber had looked in vain for fast neutrinos in the neutrino beam. Simon van der Meer’s neutrino horn, intended to improve this situation, had just finished its design stage.

Addressing CERN Council for the first time on the problem of the long-range future of CERN, the new director-general strongly emphasized two directions of development that, as subsequent history has shown, were decisive for CERN’s future success. One project, based on design work by Kjell Johnson and collaborators, foresaw the construction of storage rings, the other was aimed at a much larger “300 GeV accelerator”.

The financial implications of such proposals and the necessity to formalize budget preparations for more than one year in advance led to the creation of a working group headed by the Dutch delegate Jan Bannier. From this group emerged the remarkable “Bannier procedure”, under which firm and provisional estimates of budget figures for the coming years are fixed annually. It was decided that the cost-variation index should not be provided automatically, and that Council should make a decision on this index each year.

First research successes

The discovery that different neutrinos came from electrons and from muons was made in 1962 not at CERN, but at Brookhaven. In retrospect it became clear that CERN’s attempt was bound to fail for technical reasons. The disappointment, however, did not overshadow some remarkable successes in the first full year of CERN under Weisskopf’s leadership. The shrinking of the diffraction peak in elastic proton collisions was first seen at CERN – in agreement with the new ideas of Regge pole theory, which had also originated in Europe. The cascade antihyperon was found simultaneously with Brookhaven, but the beta decay of the pi meson and the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon were “pure” CERN discoveries. For the first time, development of a novel type of scanning device for bubble-chamber pictures (the Hough-Powell device), which started at CERN, was taken over by US institutions. Still, Weisskopf had to complain to Council about the “equipment gap” at the proton synchrotron, caused by the lack of increase in real value of the budgets in 1960 and 1961.

In some sense, the most important experimental result of 1963 was the determination of the positive relative parity between the lambda and the sigma-hyperon, obtained at CERN in the evaluation of data from the 80 cm bubble chamber. This result was in disagreement with predictions from a much-publicized idea of Heisenberg, and gave further support to the growing confidence in internal symmetries. Despite a long shutdown, needed at the proton synchrotron to install the fast ejection mechanism giving extracted beam energies of up to 25 GeV, the proton synchrotron now began its reliable and faithful operation, which, to this day, is the basis of all accelerator physics at CERN. Thanks to a neutrino beam that was 50 times as intense as that at Brookhaven, the first bubble chamber pictures of neutrino events were made.

The year 1963 saw the creation of a new body of European physicists under the chairmanship of Edoardo Amaldi. Taking into account future plans outside Europe, this body strongly recommended the storage-ring project, as well as the plans for a 300 GeV accelerator. CERN Council authorized a “supplementary programme” for 1964 to study the technical implications of these two projects. This Amaldi Committee, set up as a working group of CERN’s Scientific Policy Committee, was the forerunner of ECFA, the European Committee for Future Accelerators, founded three years later, again under the chairmanship of Amaldi. ECFA has remained ever since the independent “parliament” of European particle physicists.

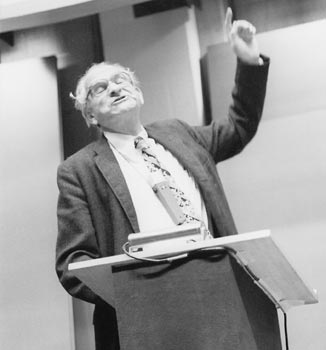

Weisskopf’s clear vision of the importance of education resulted in his legendary theoretical seminars for experimentalists at CERN. I had the privilege of being allowed to collaborate with him at that time on some aspects of the preparation of these seminars, and my view of theoretical physics has been decisively influenced by Weisskopf’s insistence on stressing the physical basis of new theoretical methods.

From 1964, CERN’s synchrocyclotron started to concentrate on nuclear physics alone, whereas the proton synchrotron was now the most intensive and most reliable accelerator in the world. Another world premiere was the first radiofrequency separator, allowing K-meson beams of unprecedented energy. At CERN, also for the first time, small online computers were employed in electronic experiments. A flurry of fluctuating excitement was caused by the analysis of muon and muon-electron pairs in the neutrino events seen in the spark chamber. When it turned out that they could not have been produced by the intermediate W-boson (to be discovered at CERN exactly 20 years later, at much higher energies), these events were more or less disregarded. Only 10 years later, after the charmed quark was found in the US, was it realized that these events were examples of charm decay – admittedly very difficult to understand on the basis of the knowledge of 1964. The unsuccessful hunt for free quarks also started in 1964, together with the acceptance of the concept of quarks as the fundamental building blocks of matter.

Relentless prodding

Thanks to Weisskopf’s relentless prodding in 1964, CERN member states were convinced that the time was ripe for a decision on the future programme of CERN. Rather than rush into an easier, but one-sided decision, Weisskopf was careful to emphasize the need for a comprehensive step involving three elements:

• further improvements of existing CERN facilities, comprising, among other things, two very large bubble chambers containing respectively 25 cubic metres of hydrogen and 10 cubic metres of heavy liquid;

• the construction of intersecting storage rings (ISR) on a new site offered by France, adjacent to the existing laboratory;

• and the construction of a 300 GeV proton accelerator “somewhere in Europe”.

Although a decision had to be postponed in 1964 – due to the difficult procedure to be set up for the site selection of the new 300 GeV laboratory – optimism prevailed that such a decision would be possible in 1965. After recommending the ISR supplementary programme in June 1965, the formal decision by Council was finally taken in December 1965.

The novel ISR project had no counterpart elsewhere in the world. Although experience had been gained at the CESR test ring for stacking electrons and for ultrahigh vacuum, this bold decision reflected the increasing self-confidence of European physics. Thus, the foundation stone was laid for the dominating role of European collider physics, which eventually led to the antiproton-proton collider, the LEP electron-positron collider and the LHC proton collider.

At the same time as the ISR project was authorized, a supplementary programme for the preparation of the 300 GeV project was also approved.

When Weisskopf’s mandate ended at the end of 1965, particle physics had passed through, perhaps, its most important stage of development. From an appendix to nuclear physics and cosmic-ray experiments, it had become a field with genuine new methods and results. The many new particle states disentangled by CERN and other laboratories gradually found a place in a framework determined by a new substructure, the quarks. In addition, many new discoveries in weak interactions, and especially at the unique neutrino beam of CERN, showed close similarities between weak and electromagnetic interactions and paved the way for unified field theory.

An important part of the enthusiasm that enabled CERN experimentalists to participate so successfully was certainly due to Weisskopf. It is still remembered at CERN how Weisskopf made a point of regularly visiting and talking to the experimentalists at their experiments. More than once he visited experiments during the night. These frequent contacts on the experimental floor with physicists at all levels gave CERN a new atmosphere and even created contacts between different groups – something that was lacking before. Weisskopf himself was aware of this. When asked on his departure from CERN what he thought his main contribution had been, he replied that administration, committees etc. would have functioned perfectly well without him. But he thought that he had just given CERN “atmosphere”.

During the Weisskopf era, directions were set for the distant future. Almost 40 years later, the basis of the CERN programme is still determined by those decisions taken in 1965. How could Weisskopf have been so successful in his promotion of CERN in Europe, dealing with member states among which at any given time there always was at least one with special problems regarding the support of particle physics and CERN?

Politicians have to trust valued experts. Weisskopf could achieve so much for the laboratory because he was deeply trusted by the representatives of the member states. Although enthusiastic in the support of new ideas in scientific projects, he never lost his self-critical attitude, quick to try to understand opposing points of view in science, and in scientific policy. The enthusiasm, honesty and modesty of Victor Weisskopf left a rich inheritance and have determined the future of CERN.