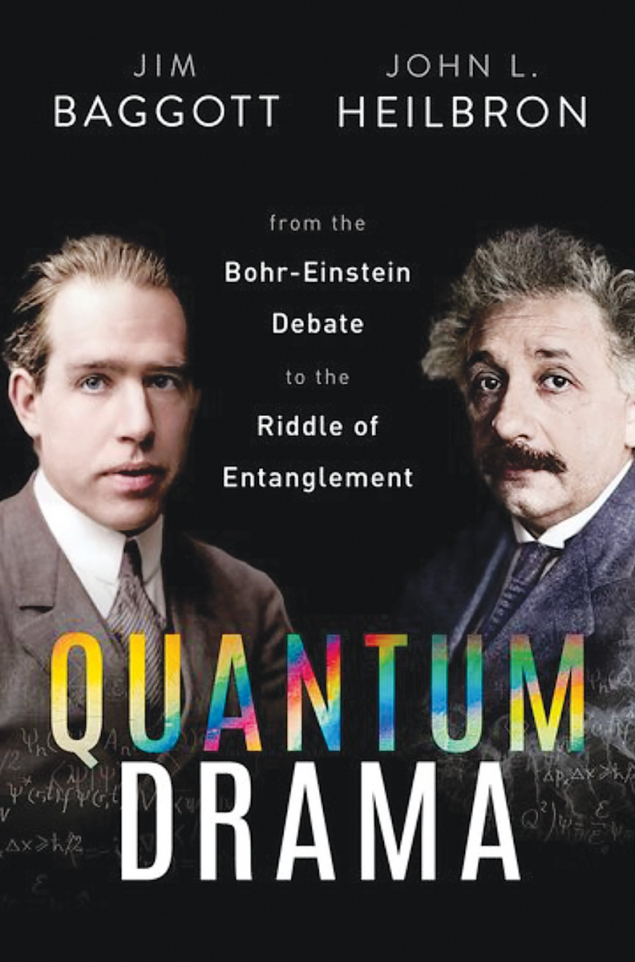

Quantum Drama, by Jim Baggott and John L Heilbron, Oxford University Press

When I was an undergraduate physics student in the mid-1980s, I fell in love with the philosophy of quantum mechanics. I devoured biographies of the greats of early-20th-century atomic physics – physicists like Bohr, Heisenberg, Schrödinger, Pauli, Dirac, Fermi and Born. To me, as I was struggling with the formalism of quantum mechanics, there seemed to be something so exciting, magical even, about that era, particularly those wonder years of the mid-1920s when its mathematical framework was being developed and the secrets of the quantum world were revealing themselves.

I went on to do a PhD in nuclear reaction theory, which meant I spent most of my time working through mathematical derivations, becoming familiar with S-matrices, Green’s functions and scattering amplitudes, scribbling pages of angular-momentum algebra and coding in Fortran 77. And I loved that stuff. There certainly seemed to be little time for worrying about what was really going on inside atomic nuclei. Indeed, I was learning that even the notion of something “really going on” was a vague one. My generation of theoretical physicists were still being very firmly told to “shut up and calculate”, as many adherents of the Copenhagen school of quantum mechanics were keen to advocate. To be fair, so much progress has been made over the past century, in nuclear and particle physics, quantum optics, condensed-matter physics and quantum chemistry, that philosophical issues were seen as an unnecessary distraction. I recall one senior colleague, frustrated by my abiding interest in interpretational matters, admonishing me with: “Jim, an electron is an electron is an electron. Stop trying to say more about it.” And there certainly seemed to be very little in the textbooks I was reading about unresolved issues arising from such topics as the EPR (Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen) paradox and the measurement problem, let alone any analysis of the work of Hugh Everett and David Bohm, who were regarded as mavericks. The Copenhagen hegemony ruled supreme.

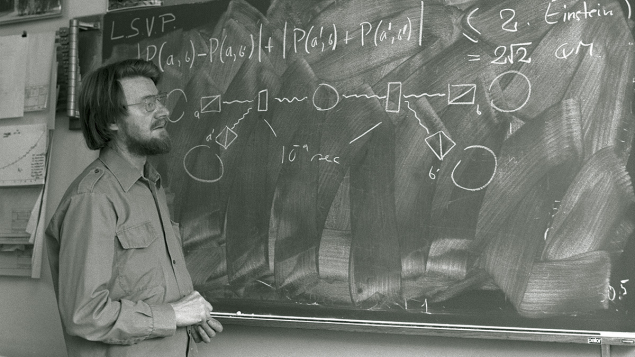

What I wasn’t aware of until later in my career was that a community of physicists had indeed continued to worry and think about such matters. These physicists were doing more than just debating and philosophising – they were slowly advancing our understanding of the quantum world. Experimentalists such as Alain Aspect, John Clauser and Anton Zeilinger were devising ingenious experiments in quantum optics – all three of whom were only awarded the Nobel Prize for their work on tests of John Bell’s famous inequality in 2022, which says a lot about how we are only now acknowledging their contribution. Meanwhile, theorists such as Wojciech Zurek, Erich Joos, Deiter Zeh, Abner Shimony and Asher Peres, to name just a few, were formalising ideas on entanglement and decoherence theory. It is certainly high time that quantum-mechanics textbooks – even advanced undergraduate ones – should contain their new insights.

All of which brings me to Quantum Drama, a new popular-science book and collaboration between the physicist and science writer Jim Baggott and the late historian of science John L Heilbron. In terms of level, the book is at the higher end of the popular-science market and, as such, will probably be of most interest to, for example, readers of CERN Courier. If I have a criticism of the book it is that its level is not consistent. For it tries to be all things. On occasion, it has wonderful biographical detail, often of less well-known but highly deserving characters. It is also full of wit and new insights. But then sometimes it can get mired in technical detail, such as in the lengthy descriptions of the different Bell tests, which I imagine only professional physicists are likely to fully appreciate.

Having said that, the book is certainly timely. This year the world celebrates the centenary of quantum physics, since the publication of the momentous papers of Heisenberg and Schrödinger on matrix and wave mechanics, in 1925 and 1926, respectively. Progress in quantum information theory and in the development of new quantum technologies is also gathering pace right now, with the promise of quantum computers, quantum sensing and quantum encryption getting ever closer. This all provides an opportunity for the philosophy of quantum mechanics to finally emerge from the shadows into mainstream debate again.

A new narrative

So, what makes Quantum Drama stand out from other books that retell the story of quantum mechanics? Well, I would say that most historical accounts tend to focus only on that golden age between 1900 and 1927, which came to an end at the Solvay Conference in Brussels and those well-documented few days when Einstein and Bohr had their debate about what it all means. While these two giants of 20th-century physics make the front cover of the book, Quantum Drama takes the story on beyond that famous conference. Other accounts, both popular and scholarly, tend to push the narrative that Bohr won the argument, leaving generations of physicists with the idea that the interpretational issues had been resolved – apart that is, from the odd dissenting voices from the likes of Everett or Bohm who tried, unsuccessfully it was argued, to put a spanner in the Copenhagen works. All the real progress in quantum foundations after 1927, or so we were told, was in the development of quantum field theories, such as QED and QCD, the excitement of high-energy physics and the birth of the Standard Model, with the likes of Murray Gell-Mann and Steven Weinberg replacing Heisenberg and Schrödinger at centre stage. Quantum Drama takes up the story after 1927, showing that there has been a lively, exciting and ongoing dispute over what it all means, long after the death of those two giants of physics. In fact, the period up to Solvay 1927 is all dealt with in Act I of the book. The subtitle puts it well: From the Bohr–Einstein Debate to the Riddle of Entanglement.

The Bohr–Einstein debate is still very much alive and kicking

All in all, Quantum Drama delivers something remarkable, for it shines a light on all the muddle, complexity and confusion surrounding a century of debate about the meaning of quantum mechanics and the famous “Copenhagen spirit”, treating the subject with thoroughness and genuine scholarship, and showing that the Bohr–Einstein debate is still very much alive and kicking.