Gravitational waves (GWs) crease and stretch the fabric of spacetime as they ripple out across the universe. As they pass through regions where beams circulate in storage rings, they should therefore cause charged-particle orbits to seem to contract, as they climb new peaks and plumb new troughs, with potentially observable effects.

Proposals in this direction have appeared intermittently over the past 50 years, including during and after the construction of LEP and the LHC. Now that the existence of GWs has been established by the LIGO and VIRGO detectors, and as new, even larger storage rings are being proposed in Europe and China, this question has renewed relevance. We are on the cusp of the era of GW astronomy — a young and dynamic domain of research with much to discover, in which particle accelerators could conceivably play a major role.

From 2 February to 31 March this year, a topical virtual workshop titled “Storage Rings and Gravitational Waves” (SRGW2021) shone light on this tantalising possibility. Organised within the European Union’s Horizon 2020 ARIES project, the meeting brought together more than 100 accelerator experts, particle physicists and members of the gravitational-physics community to explore several intriguing proposals.

Theoretically subtle

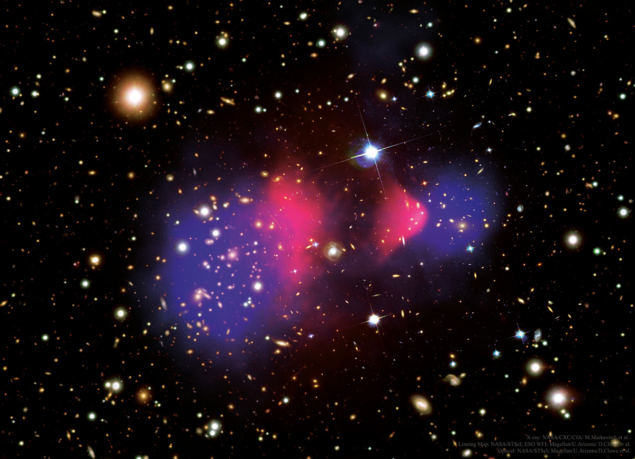

GWs are extremely feebly interacting. The cooling and expanding universe should have become “transparent” to them early in its history, long before the timescales probed through other known phenomena. Detecting cosmological backgrounds of GWs would, therefore, provide us with a picture of the universe at earlier times that we can currently access, prior to photon decoupling and Big-Bang nucleosynthesis. It could also shed light on high-energy phenomena, such as high-temperature phase transitions, inflation and new heavy particles that cannot be directly produced in the laboratory.

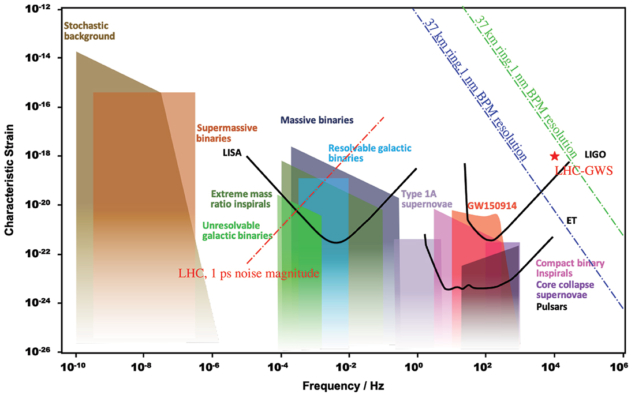

In the opening session of the workshop, Jorge Cervantes (ININ Mexico) presented a vivid account of the history of GWs, revealing how subtle they are theoretically. It took about 40 years and a number of conflicting papers to definitively establish their existence. Bangalore S. Sathyaprakash (Penn State and Cardiff) reviewed the main expected sources of GWs: the gravitational collapse of binaries of compact objects such as black holes, neutron stars and white dwarfs; supernovae and other transient phenomena; spinning neutron stars; and stochastic backgrounds with either astrophysical or cosmological origins. The GW frequency range of interest extends from 0.1 nHz to 1 MHz (see figure “Sources and sensitivities”).

The frequency range of interest extends from 0.1 nHz to 1 MHz

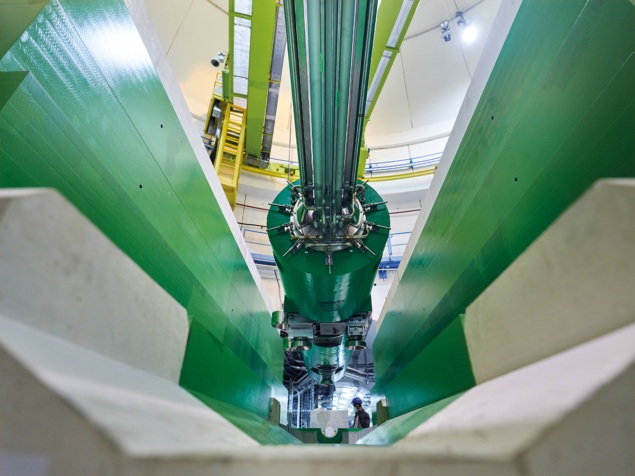

Raffaele Flaminio (LAPP Annecy) reviewed the mindboggling precision of VIRGO and LIGO, which can measure motion 10,000 times smaller than the width of an atomic nucleus. Jörg Wenninger (CERN) reported the similarly impressive sensitivity of LEP and the LHC to small effects, such as tides and earthquakes on the other side of the planet. Famously, LEP’s beam-energy resolution was so precise that it detected a diurnal distortion of the 27 km ring at an amplitude of a single millimetre, and the LHC beam-position-monitor system can achieve measurement resolutions on the average circumference approaching the micrometre scale over time intervals of one hour. While impressive, given that these machines are designed with completely different goals in mind, it is still far from the precision achieved by LIGO and VIRGO. However, one can strongly enhance the sensitivity to GWs by exploiting resonant effects and the long distances travelled by the particles over their storage times. In one hour, protons at the LHC travel through the ring about 40 million times. In principle, the precision of modern accelerator optics could allow storage rings and accelerator technologies to cover a portion of the enormous GW frequency range of interest.

Resonant Responses

Since the invention of the synchrotron, storage rings have been afflicted by difficult-to-control resonance effects which degrade beam quality. When a new ring is commissioned, accelerator physicists work diligently to “tune” the machine’s parameters to avoid such effects. But could accelerator physicists turn the tables and seek to enhance these effects and observe resonances caused by the passage of GWs?

In accelerators and storage rings, charged particles are steered and focused in the two directions transverse to their motion by dipole, quadrupole and higher-order magnets — the “betatron motion” of the beam. The beam is also kept bunched in the longitudinal plane as a result of an energy-dependent path length and oscillating electric fields in radio-frequency (RF) cavities — the “synchrotron motion” of the beam. A gravitational wave can resonantly interact with either the transverse betatron motion of a stored beam, at a frequency of several kHz, or with the longitudinal synchrotron motion at a frequency of tens of hertz.

Katsunobu Oide (KEK and CERN) discussed the transverse betatron resonances that a gravitational wave can excite for a beam circulating in a storage ring. Typical betatron frequencies for the LHC are a few kHz, offering potentially sensitivity to GWs with frequencies of a similar order of magnitude. Starting from a standard 30 km ring, Oide-san proposed special beam-optical insertions with a large beta function, which would serve as “GW antennas” to enhance the resonance strength, resulting in 37.5 km-long optics (see figure “Antenna optics”). Among several parameters, the sensitivity to GWs should depend on the size of the ring. Oide derived a special resonance condition of kGWR±2=Qx, with R the ring radius, kGW the GW wave number and Qx the horizontal betatron tune.

Suvrat Rao (Hamburg University) presented an analysis of the longitudinal beam response of the LHC. An impinging GW affects the revolution period, in a similar way to the static gravitational gradient effect due to the presence of the Mont Blanc (which alters the revolution time at the level of 10-16 s) and the diurnal effect of the changing locations of sun and moon (10-18 s) — the latter effect being about six orders of magnitude smaller than the tidal effect on the ring circumference.

The longitudinal beam response to a GW should be enhanced for perturbations close to the synchrotron frequency, which, for the LHC, would be in the range 10 to 60 Hz. Raffaele D’Agnolo (IPhT) estimated the sensitivity to the gravitational strain, h, at the synchrotron frequency, without any backgrounds, as h~10-13, and listed three possible paths to further improve the sensitivity by several orders of magnitude. Rao also highlighted that storage-ring GW detection potentially allows for an earth-based GW observatory sensitive to millihertz GWs, which could complement space-based laser interferometers such as LISA, which is planned to be launched in 2034. This would improve the sky-localisation GW-source, which is useful for electromagnetic follow-up studies with astronomical telescopes.

Out of the ordinary

More exotic accelerators were also mooted. A “coasting-beam” experiment might have zero restoring voltage and no synchrotron oscillations. Cold “crystalline” beams of stable ordered 1D, 2D or 3D structures of ions could open up a whole new frequency spectrum, as the phonon spectrum which could be excited by a GW could easily extend up to the MHz range. Witek Krasny (LPNHE) suggested storing beams consisting of “in the LHC: decay times and transition rates could be modified by an incident GW. The stored particles could, for example, include the excited partially stripped heavy ions that are the basis of a “gamma factory”.

Finally on the storage-ring front, Andrey Ivanov (TU Vienna) and co-workers discussed the possibly shrinking circumference of a storage ring, such as the 1.4 km light source SPring-8 in Japan, under the influence of the relic GW background.

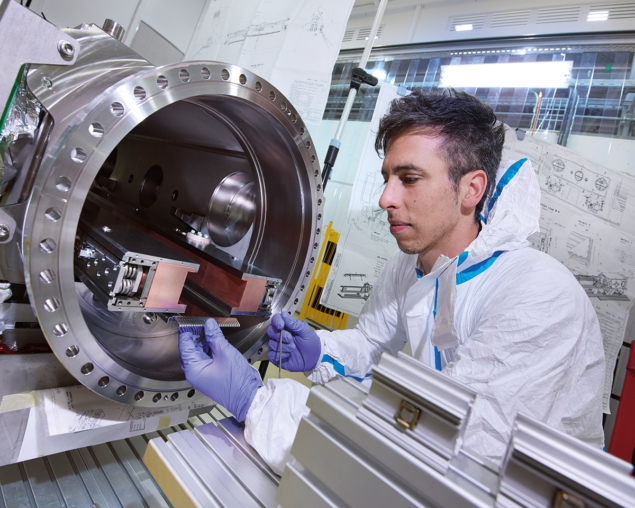

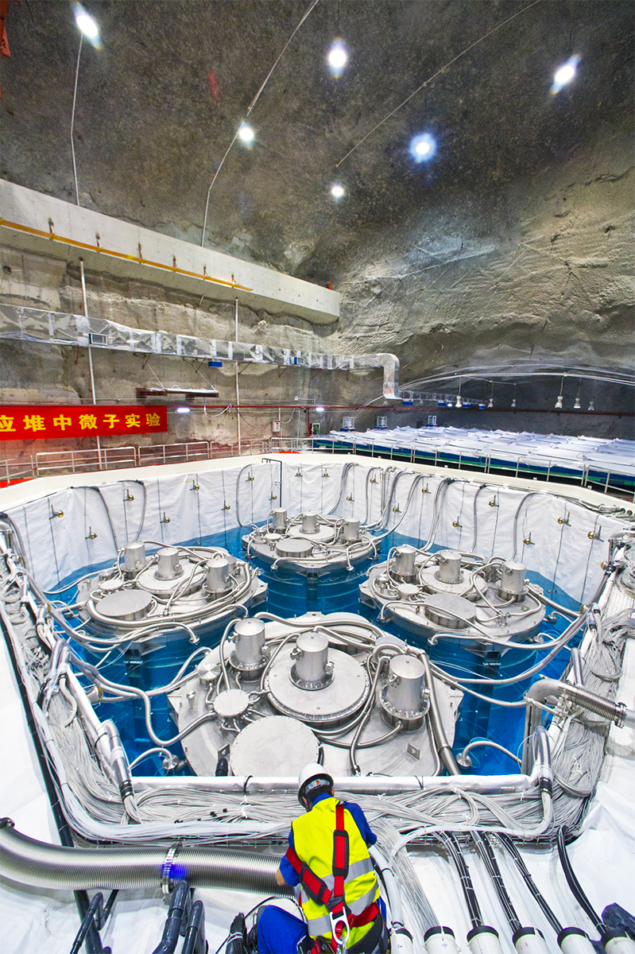

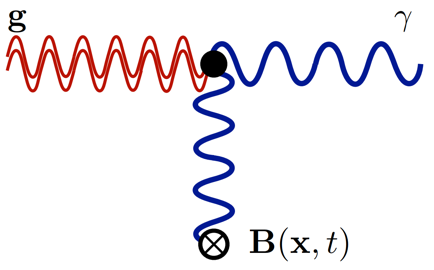

Delegates at SRGW2021 also proposed completely different ways of using accelerator technology to detect GWs. Sebastian Ellis (IPhT) explained how an SRF cavity might act as a resonant bar or serve as a Gertsenshtein converter, in both cases converting a graviton into a photon in the presence of a strong background magnetic field and yielding a direct electromagnetic signal — similar to axion searches. Related attempts at GW detection using cavities were pioneered in the 1970s by teams in the Soviet Union and Italy, but RF technology has made big strides in quality factors, cooling and insulation since then, and a new series of experiments appears to be well justified.

Another promising approach for GW detection is atomic-beam interferometry. Instead of light interference, as in LIGO and VIRGO, an incident GW would cause interference between carefully prepared beams of cold atoms. This approach is being pursued by the recently approved AION experiment using ultra-cold-strontium atomic clocks over increasingly large path lengths, including the possible use of an LHC access shaft to house a 100-metre device targeting the 0.01 to 1 Hz range. Meanwhile, a space-based version, AEDGE, could be realised with a pair of satellites in medium earth orbit separated by 4.4×107 m.

Storage rings as sources

Extraordinarily, storage rings could act not only as GW detectors, but also as observable sources of GWs. Pisin Chen (NTU Taiwan) discussed how relativistic charged particles executing circular orbital motion can emit gravitational waves in two channels: “gravitational synchrotron radiation” (GSR) emitted directly by the massive particle, and “resonant conversion” in which, via the Gertsenshtein effect, electromagnetic synchrotron radiation (EMSR) is converted into GWs.

Gravitons could be emitted via “gravitational beamstrahlung”

John Jowett (GSI, retired from CERN) and Fritz Caspers (also retired from CERN) recalled that GSR from beams at the SPS and other colliders had been discussed at CERN as early as the 1980s. It was realised that these beams would be among the most powerful terrestrial sources of gravitational radiation although the total radiated power would still be many orders of magnitude lower than from regular synchrotron radiation. The dominant frequency of direct GSR is the revolution frequency, 10 kHz, while the dominant frequency of resonant EMSR-GSR conversion is a factor γ3 higher, around 10 THz at the LHC, conceivably allowing the observation of gravitons. If all particles and bunches of a beam excited the GW coherently, the space-time metric perturbation has been estimated to be as large as hGSR~10-18. Gravitons could also be emitted via “gravitational beamstrahlung” during the collision with an opposing beam, perhaps producing the most prominent GW signal at future proposed lepton colliders. At the LHC, argued Caspers, such signals could be detected by a torsion-balance experiment with a very sensitive, resonant mechanical pickup installed close to the beam in one of the arcs. In a phase-lock mode of operation, an effective resolution bandwidth of millihertz or below could be possible, opening the exciting prospect of detecting synthetic sources of GWs.

Towards an accelerator roadmap

The concluding workshop discussion, moderated by John Ellis (King’s College London), focused on the GW-detection proposals considered closest to implementations: resonant betatron oscillations near 10 kHz; changes in the revolution period using “low-energy” coasting ion-beams without a longitudinally focusing RF system; “heterodyne” detection using SRF cavities up to 10 MHz; beam-generated GWs at the LHC; and atomic interferometry. These potential components of a future R&D plan cover significant regions of the enormous GW frequency space.

Apart from an informal meeting at CERN in the 1990s, SRGW2021 was the first workshop to link accelerators and GWs and bring together the implicated scientific communities. Lively discussions in this emerging field attest to the promise of employing accelerators in a completely different way to either detect or generate GWs. The subtleties of the particle dynamics when embedded in an oscillating fabric of space and time, and the inherent sensitivity problems in detecting GWs, pose exceptional challenges. The great interest prompted by SRGW2021, and the tantalising preliminary findings from this workshop, call for more thorough investigations into harnessing future storage rings and accelerator technologies for GW physics.