The Saclay Research Centre near Paris is the largest of the French Atomic Energy Commission’s research centres. Conceived from the start as a multi-purpose centre to bring together fundamental research and technical innovation, it has since expanded to explore many different aspects of nuclear physics and its applications, including, of course, particle physics. In 1963, when physicists from Saclay began experiments on the PS at CERN, it marked the start of a long and fruitful collaboration between the two laboratories. By the time the LHC is commissioned, this collaboration will have encompassed more than 30 different experiments, to which Saclay has brought its expertise in instrumentation, data acquisition and data analysis.

The bubble-chamber era

When researchers from Saclay first came to CERN in the 1960s, the majority of experiments in particle physics involved bubble chambers. Saclay was one of the pioneers of their construction and use at a number of accelerators: first Saturne at Saclay, then Nimrod – the Rutherford Laboratory’s 8 GeV proton synchrotron – and then the PS at CERN and the 70 GeV accelerator at Serpukhov. The first series of experiments at the PS by physicists from Saclay’s SPCHE (see “The early days of Saclay” box) involved the use of an 81 cm hydrogen bubble chamber. This was developed by the technical services at Saturne for the laboratory of the Ecole Polytechnique under the leadership of Bernard Gregory, who later became director-general of CERN. The chamber was used to study K– p, K– n, π– p, π+ n and pbar-p scattering at energies of a few GeV, with the aim being to understand the collision mechanisms. The same theme was repeated, but at higher energies, in a second series of experiments at the PS on CERN’s 2 m hydrogen bubble chamber.

The 1970s saw a further increase in collision energy, and bubble chambers became bigger and bigger in line with the increasing multiplicity and energy of the final particles. In 1971, André Lagarrigue led the construction of the Gargamelle bubble chamber at the Saturne laboratory. Exposed to the neutrino beam from CERN’s PS, Gargamelle led to the discovery of neutral currents in 1973. This was followed by the Big European Bubble Chamber (BEBC) at the SPS, which involved energies approximately 10 times higher than at the PS. In addition to investigating strong interaction mechanisms and resonances, these experiments also explored neutrino-nucleon and antineutrino-nucleon scattering, the first stage in a better understanding of neutrino physics.

During its 30 years of bubble-chamber experiments, Saclay’s DPhPE (Département de physique des particules élémentaires) – which the SPCHE had become in 1966 – built up strong teams, of around 150 people, that specialized in the scanning and measurement of images, before going on to develop automatic scanning techniques that allowed more than 10 million images to be analysed. As a result the DPhPE, together with CERN, had the greatest measurement and data-handling capacity of any European laboratory, and so was able to play a major role in the collaborations in which it participated. In developing bubble chambers, the DPhPE’s technical services also acquired skills in the fields of magnetism, cryogenics and control systems, as well as experience in the design, construction and running of large projects. This expertise was to come in useful in the new generation of experiments at CERN in which the DPhPE took part.

The first electronic experiments

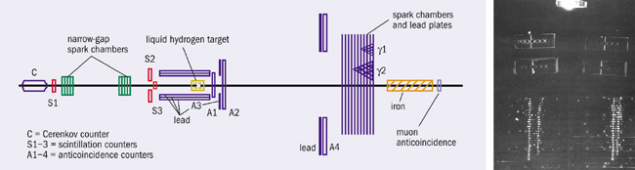

The spark chamber was invented at the beginning of the 1960s, and when used in conjunction with counters equipped with fast electronic read-out systems, it allowed events to be pre-selected – something that is impossible in bubble chambers. Spark chambers are also able to record signals much more quickly than bubble chambers, and their use became widespread in high-energy physics, marking the start of the “electronic” detector era. The SPCHE soon turned to this new technology. Its first electronic experiment at CERN, performed in 1964 by the team of Paul Falk-Vairant, involved the measurement of the high-energy charge exchange reaction π– p → π0 n at the PS, in an extension of an earlier experiment at Saturne. The equipment designed at the SPCHE consisted of scintillation counters and optical spark chambers to detect electromagnetic showers. Working first with a liquid hydrogen target, the experiment seemed to confirm the simple Regge pole theory favoured at the time; but when carried out with a polarised target, the results showed that a more complex interpretation was needed.

The DPhPE continued its extensive study of strong interaction mechanisms at the PS and also began to study strange particles following the 1964 demonstration of CP violation in the neutral kaon system, to which Réne Turlay, later a key figure at Saclay, contributed. In 1971, the start-up of the Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR) at CERN allowed matter to be explored at much higher energies, and physicists from the DPhPE took part in two experiments there. One of these was R702, whose purpose was to measure the production of particles with large transverse momentum, and whose results corroborated the theory of the granular structure of protons. In these early electronic experiments, the DPhPE contributed detector elements and the associated electronics commonly used at the time: scintillation counters for the trigger, Cerenkov counters for identifying particles, spark chambers for measuring trajectories, and polarised targets. The end of the 1960s saw the appearance of wire chambers for tracking, which were faster and more precise than spark chambers, and which allowed detectors to be built that were larger and easier to operate.

By 1977 when CERN’s 200-400 GeV proton synchrotron, the SPS, was commissioned, the results from the previous 15 years had changed the perception of particle physics. In particular, the discoveries of neutral currents at Gargamelle in 1973 and of charmed particles in 1974 represented an initial experimental validation of the Glashow-Weinberg-Salam theory of the electroweak force and of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the theory of strong interaction. The various experiments at the SPS set out to test these theories in more depth. The DPhPE played an active role, taking part in the deep inelastic scattering experiments with neutrinos (CDHS) and muons (BCDMS), as well as experiments in hadroproduction (WA11, NA3) and photoproduction (NA14). These brought a large haul of results to which the DPhPE’s physicists made significant contributions: measurement of nucleon structure functions, confirmation of violations of the scale-invariance predicted by QCD, precise measurements of sin2ΘW and αs, and charm studies.

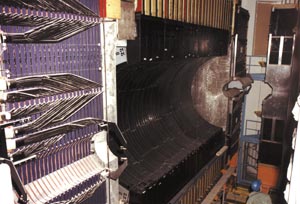

DPhPE built proportional chambers or drift chambers of various sizes and geometries for all of these experiments at the SPS. Given the large number of wire chambers that were needed, the assembly lines the laboratory had at that time were a valuable asset. In particular, large 4 m sided hexagonal chambers were designed for the CDHS, and were subsequently used in numerous detector tests under beam conditions before being integrated in the recent CHORUS experiment. The DPhPE also built its first large-scale calorimeter for the NA3 experiment. Comprising lead plates and scintillating tiles, its size (5 m x 2 m) necessitated the development of a new low-cost type of scintillator with a high attenuation length. Again the skills acquired through participation in these projects were put to good use in the next generation of experiments.

In the 1980s, CERN took the major step of converting its SPS into a 540 GeV proton-antiproton collider, which later ran at 630 GeV. Commissioned in 1981, the SppbarS and its two general-purpose experiments, UA1 and UA2, led to the discovery of the W± and Z bosons, bringing resounding proof of the Glashow-Weinberg-Salam model for electroweak interactions (“When CERN saw the end of the alphabet”). The DPhPE took part in both experiments, contributing not only through technical achievements but also in obtaining physics results, in particular regarding the W± and Z bosons, jets, and the search for the top quark. Building on its experience with NA3, the DPhPE became involved in calorimetry in both UA1 and UA2, with lead-sandwich electromagnetic calorimeters and scintillators for the UA1 and UA2 endcaps, followed by scintillating optical fibre detectors for the fibre tracker for the second phase of UA2. The scintillator “gondolas” of the UA1 calorimeter, a key component in identifying and reconstructing the decays of the W± and Z bosons based on electron decay, were one of the DPhPE’s most significant achievements in terms of the specific developments and equipment needed, including the development of a new extruded polystyrene scintillator that allowed large thin leaves of uniform thickness to be made.

The LEP era

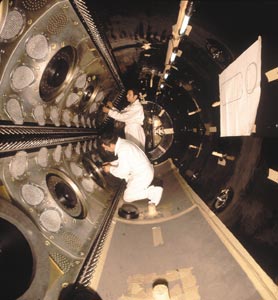

The DPhPE was involved in LEP right from the outset, and participated in the ALEPH, DELPHI and OPAL experiments. In ALEPH, the contributions involved the superconducting solenoid – which was 5 m in diameter, 7 m long, with a field of 1.5 T – the lead-sandwich electromagnetic calorimeter that incorporated proportional tubes, and the silicon-tungsten luminosity calorimeter. For DELPHI, the DPhPE was involved with the tracker – a time projection chamber – and its associated data acquisition and read-out electronics. For OPAL, the contributions included the scintillator hodoscope for time-of-flight measurement and general trigger electronics. The 12 years of data taking at LEP contributed in many essential ways to refining the Standard Model. Physicists from DAPNIA, which the DPhPE became in 1991, were involved in this progress, taking part in, for example, beauty studies, the accurate measurement of the W boson mass, and the search for the Higgs boson and supersymmetric particles.

At the end of the 1980s, as the experiments at LEP progressed, the fixed-target programme began to focus again on the subjects for which this kind of experiment is still the most suited. The DPhPE decided to be involved in four experiments, namely CP violation in the neutral-kaon system (CP LEAR, then NA48), nucleon spin structure (NMC, SMC, then COMPASS), neutrino oscillation (NOMAD) and quark-gluon plasma (NA34). While most of these experiments have been completed, NA48 and COMPASS are still taking data.

Into the 21st century

Chambers are still the dominant instrument in particle physics but technologies have evolved, resulting for example in the “micromégas” (micromesh gaseous structure) chambers, which are able to absorb particle fluxes 1000 times more intense than conventional chambers, and which are also faster and more accurate. Developed by the DPhPE, together with the necessary state-of-the-art electronics, these chambers are used in COMPASS and have recently been adopted by the CAST experiment.

At the same time, the make-up of the Saclay teams has also evolved. The particle physicists no longer have a monopoly on experiments at CERN. They have been joined by teams of nuclear physicists from DAPNIA, studying the structure of the nucleus in the SMC and COMPASS experiments, for example, and in the neutron time-of-flight programme (nTOF). The future of the fixed-target programme at CERN also concerns DAPNIA, whose physicists and engineers are contributing to the proposal for a future Superconducting Proton Linac (SPL) accelerator complex at CERN, and to the design of experiments that would use the SPL’s intense neutrino beams for the study of CP violation in the lepton sector.

From LEP to the LHC

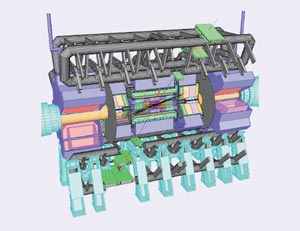

CERN’s latest machine, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), will open up a new high-energy domain, and its experiments should clarify the precise nature of the electroweak symmetry breaking mechanism once and for all. DAPNIA is investing heavily in this future, with its particle physicists taking part in the ATLAS and CMS experiments and its nuclear physicists participating in ALICE. It is also involved in designing and monitoring the manufacture of the quadrupoles for the machine itself. Participation in ATLAS involves the design of the superconducting air-cored toroid magnet system, and the construction of the central electromagnetic liquid argon calorimeter. Involvement in CMS covers the on-line calibration system for the crystal electromagnetic calorimeter, which is based on the injection of laser light, as well as the general design and monitoring of certain components of the experiment’s superconducting solenoid magnet, which is 6 m in diameter, 12.5 m long, and has a field of 4 T. In ALICE, DAPNIA is contributing the design and production of the wire chambers for the muon spectrometer. Muons, electrons and photons are all hints of the signals that these experiments hope to discover or measure, whether it be the Higgs boson at ATLAS and CMS, or the quark-gluon plasma at ALICE. What more promising subjects for the continuation of the 40 year long co-operation between Saclay and CERN could one hope for?