The ATLAS and ALICE collaborations have announced the first results of a new way to measure the “radial flow” of quark–gluon plasma (QGP). The two analyses offer a fresh perspective into the fluid-like behaviour of QCD matter under extreme conditions, such as those that prevailed after the Big Bang. The measurements are highly complementary, with ALICE drawing on their detector’s particle-identification capabilities and ATLAS leveraging the experiment’s large rapidity coverage.

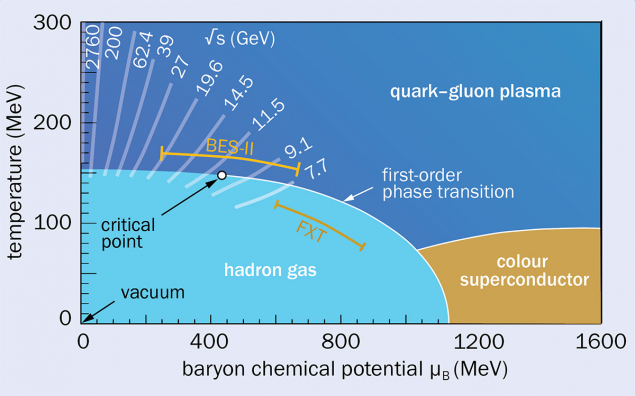

At the Large Hadron Collider, lead–ion collisions produce matter at temperatures and densities so high that quarks and gluons momentarily escape their confinement within hadrons. The resulting QGP is believed to have filled the universe during its first few microseconds, before cooling and fragmenting into mesons and baryons. In the laboratory, these streams of particles allow researchers to reconstruct the dynamical evolution of the QGP, which has long been known to transform anisotropies of the initial collision geometry into anisotropic momentum distributions of the final-state particles.

Compelling evidence

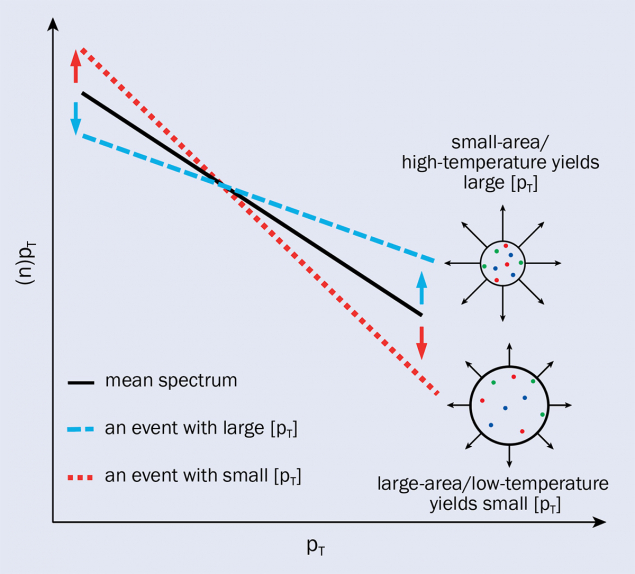

Differential measurements of the azimuthal distributions of produced particles over the last decades have provided compelling evidence that the outgoing momentum distribution reflects a collective response driven by initial pressure gradients. The isotropic expansion component, typically referred to as radial flow, has instead been inferred from the slope of particle spectra (see figure 1). Despite its fundamental role in driving the QGP fireball, radial flow lacked a differential probe comparable to those of its anisotropic counterparts.

That situation has now changed. The ALICE and ATLAS collaborations recently employed the novel observable v0(pT) to investigate radial flow directly. Their independent results demonstrate, for the first time, that the isotropic expansion of the QGP in heavy-ion collisions exhibits clear signatures of collective behaviour. The isotropic expansion of the QGP and its azimuthal modulations ultimately depend on the hydrodynamic properties of the QGP, such as shear or bulk viscosity, and can thus be measured to constrain them.

Traditionally, radial flow has been inferred from the slope of pT-spectra, with the pT-integrated radial-flow extracted via fits to “blast wave” models. The newly introduced differential observable v0(pT) captures fluctuations in spectral shape across pT bins. v0(pT) retains differential sensitivity, since it is defined as the correlation (technically the normalised covariance) between the fraction of particles in a given pT-interval and the mean transverse momentum of the collision products within a single event, [pT]. Roughly speaking, a fluctuation raising [pT] produces a positive v0(pT) at high pT due to the fractional yield increasing; conversely, the fractional yield decreasing at low pT causes a negative v0(pT). A pseudorapidity gap between the measurement of mean pT and the particle yields is used to suppress short-range correlations and isolate the long-range, collective signal. Previous studies observed event-by-event fluctuations in [pT], related to radial flow over a wide pT range and quantified by the coefficient v0ref, but they could not establish whether these fluctuations were correlated across different pT intervals – a crucial signature of collective behaviour.

Origins

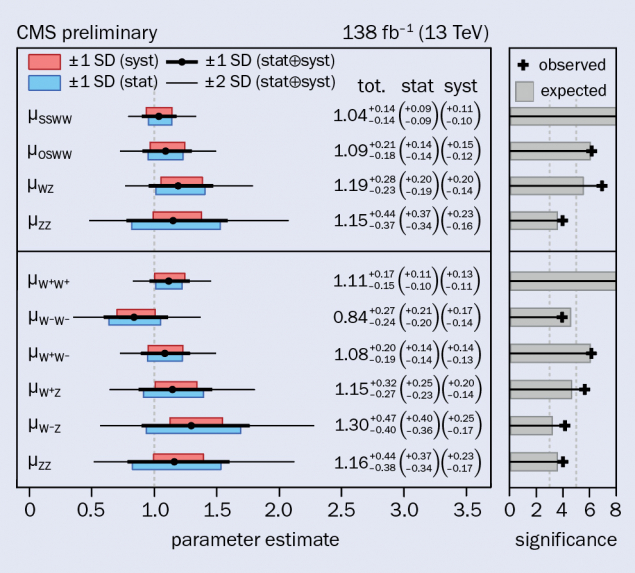

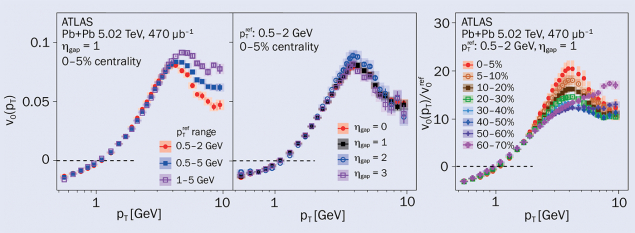

The ATLAS collaboration performed a measurement of v0(pT) in the 0.5 to 10 GeV range, identifying three signatures of the collective origin of radial flow (see figure 2). First, correlations between the particle yield at fixed pT and the event-wise mean [pT] in a reference interval show that the two-particle radial flow factorises into single-particle coefficients as v0(pT) × v0ref for pT < 4 GeV, independent of the reference choice (left panel). Second, the data display no dependence on the rapidity gap between correlated particles, suggesting a long-range effect intrinsic to the entire system (middle panel). Finally, the centrality dependence of the ratio v0(pT)/v0ref followed a consistent trend from head-on to peripheral collisions, effectively cancelling initial geometry effects and supporting the interpretation of a collective QGP response (right panel). At higher pT, a decrease in v0(pT) and a splitting with respect to centrality suggest the onset of non-thermal effects such as jet quenching. This may reveal fluctuations in jet energy loss – an area warranting further investigation.

Using more than 80 million collisions at a centre-of-mass energy of 5.02 TeV, ALICE extracted v0(pT) for identified pions, kaons and protons across a broad range of centralities. ALICE observes v0(pT) to be negative at low pT, reflecting the influence of mean-pT fluctuations on the spectral shape (see figure 3). The data display a clear mass ordering at low pT, from protons to kaons to pions, consistent with expectations from collective radial expansion. This mass ordering reflects the greater “push” heavier particles experience in the rapidly expanding medium. The picture changes above 3 GeV, where protons have larger v0(pT) values than pions and kaons, perhaps indicating the contribution of recombination processes in hadron production.

The results demonstrate that the isotropic expansion of the QGP in heavy-ion collisions exhibits clear signatures of collective behaviour

The two collaborations’ measurements of the new v0(pT) observable highlight its sensitivity to the bulk-transport properties of the QGP medium. Comparisons with hydrodynamic calculations show that v0(pT) varies with bulk viscosity and the speed of sound, but that it has a weaker dependence on shear viscosity. Hydrodynamic predictions reproduce the data well up to about 2 GeV, but diverge at higher momenta. The deviation of non-collective models like HIJING from the data underscores the dominance of final-state, hydrodynamic-like effects in shaping radial flow.

These results advance our understanding of one of the most extreme regimes of QCD matter, strengthening the case for the formation of a strongly interacting, radially expanding QGP medium in heavy-ion collisions. Differential measurements of radial flow offer a new tool to probe this fluid-like expansion in detail, establishing its collective origin and complementing decades of studies of anisotropic flow.