More than 1000 physicists took part in the ninth Large Hadron Collider Physics (LHCP) conference from 7 to 12 June. The in-person conference was to have been held in Paris: for the second year in a row, however, the organisers efficiently moved the meeting online, without a registration fee, thanks to the support of CERN and IUPAP. While the conference experience cannot be the same over a video link, the increased accessibility for people from all parts of the international community was evident, with LHCP21 participants hailing from institutes across 54 countries.

The LHCP format traditionally has plenary sessions in the mornings and late afternoons, with parallel sessions in the middle of the day. This “shape” was kept for the online meeting, with a shorter day to improve the practicality of joining from distant time zones. This resulted in a dense format with seven-fold parallel sessions, allowing all parts of the LHC programme, both experimental and theoretical, to be explored in detail. The overall vitality of the programme is illustrated by the raw statistics: a grand total of 238 talks and 122 posters were presented.

Last year saw a strong focus on the couplings to the second generation

Nine years on from the discovery of the 125 GeV Higgs boson, measurements have progressed to a new level of precision with the full Run-2 data. Both ATLAS and CMS presented new results on Higgs production, helping constrain the dynamics of the production mechanisms via differential and “simplified template” cross-section measurements. While the couplings of the Higgs to third-generation fermions are now established, last year saw a strong focus on the couplings to the second generation. After first evidence for Higgs decays to muons was reported from CMS and ATLAS results earlier in the year, ATLAS presented a new search with the full Run-2 data for Higgs decays to charm quarks using powerful new charm-tagging techniques. Both CMS and ATLAS showed updated searches for Higgs-pair production, with ATLAS being able to exclude a production rate more than 4.1 times the Standard Model (SM) prediction at 95% confidence. This is a process that should be observable with High-Luminosity LHC statistics, if it is as predicted in the SM. A host of searches were also reported, some using the Higgs as a tool to probe for new physics.

Puzzling hints

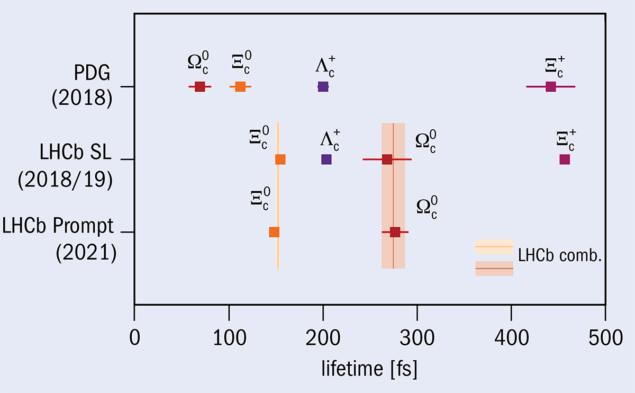

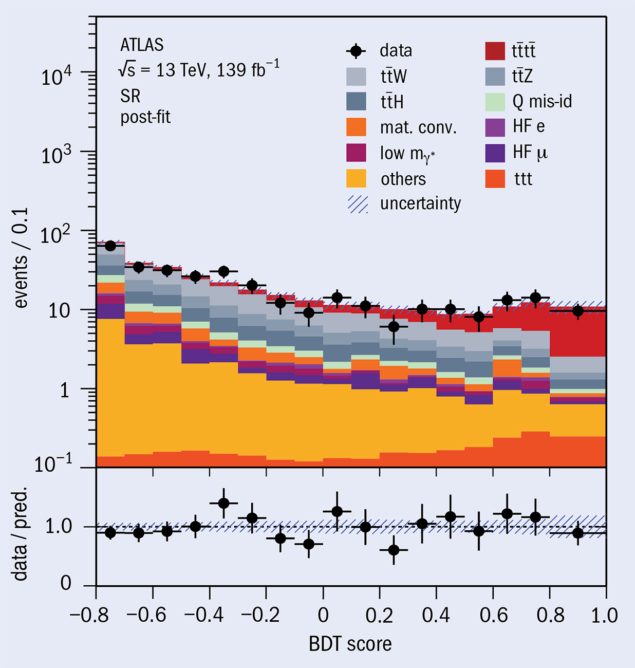

The most puzzling hints from the LHC Run 1 seem to strengthen in Run 2. LHCb presented analyses relating to the “flavour anomalies” found most notably in b→sµ+µ− decays, updated to the full data statistics, in multiple channels. While no result yet passes a 5σ difference from SM expectations, the significances continue to creep upwards. Searches by ATLAS and CMS for potential new particles or effects at high masses that could indicate an associated new-physics mechanism continue to draw a blank, however. This remains a dilemma to be studied with more precision and data in Run 3. Other results in the flavour sector from LHCb included a new measurement of the lifetime of the Ωc, four times longer than previous measurements (CERN Courier July/August 2021 p17) and the first observation of a mass difference between the mixed D0–D0 meson mass eigenstates (CERN Courier July/August 2021 p8).

A wealth of results was presented from heavy-ion collisions. Measurements with heavy quarks were prominent here as well. ALICE reported various studies of the differences in heavy-flavour hadron production in proton–proton and heavy-ion collisions, for example using D mesons. CMS reported the first observation of Bc meson production in heavy-ion collisions, and also first evidence for top-quark pair production in lead–lead collisions. ATLAS used heavy-flavour decays to muons to compare suppression of b- and c-hadron production in lead–lead and proton–proton collisions. Beyond the ions, ALICE also showed intriguing new results demonstrating that the relative rates of different types of c-hadron production differ in proton–proton collisions compared to earlier experiments using e+e− and ep collisions at LEP and HERA.

Looking forward, the experiments reported on their preparations for the coming LHC Run 3, including substantial upgrades. While some work has been slowed by the pandemic, recommissioning of the detectors has begun in preparation for physics data taking in spring 2022, with the brighter beams expected from the upgraded CERN accelerator chain. One constant to rely on, however, is that LHCP will continue to showcase the fantastic panoply of physics at the LHC.