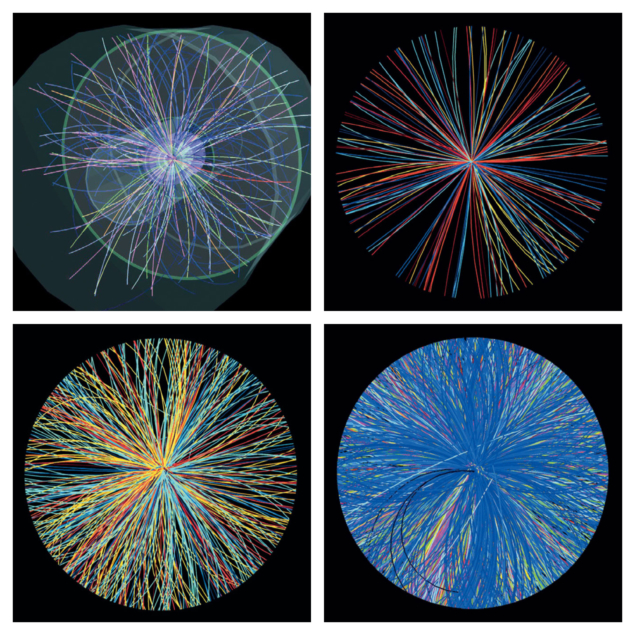

Heavy-ion collisions are used at CERN and other laboratories to re-create conditions of high temperature and high energy density, similar to those that must have characterized the first instants of the universe, after the Big Bang. Yet heavy-ion collisions are not all equal. Because heavy ions are extended objects, the system created in a central head-on collision is different from that created in a peripheral collision, where the nuclei just graze each other. Measuring just how central such collisions are at the LHC is an important part of the studies by the ALICE experiment, which specializes in heavy-ion physics. The centrality determination provides a tool to compare ALICE measurements with those of other experiments and with theoretical calculations.

Centrality is a key parameter in the study of the properties of QCD matter at extreme temperature and energy density because it is related directly to the initial overlap region of the colliding nuclei. Geometrically, it is defined by the impact parameter, b – the distance between the centres of the two colliding nuclei in a plane transverse to the collision axis (figure 1). Centrality is thus related to the fraction of the geometrical cross-section that overlaps, which is proportional to πb2/π(2RA)2, where RA is the nuclear radius. It is customary in heavy-ion physics to characterize the centrality of a collision in terms of the number of participants (Npart), i.e. the number of nucleons that undergo at least one collision, or in terms of the number of binary collisions among nucleons from the two nuclei (Ncoll). The nucleons that do not participate in any collision – the spectators – essentially keep travelling undeflected, close to the beam direction.

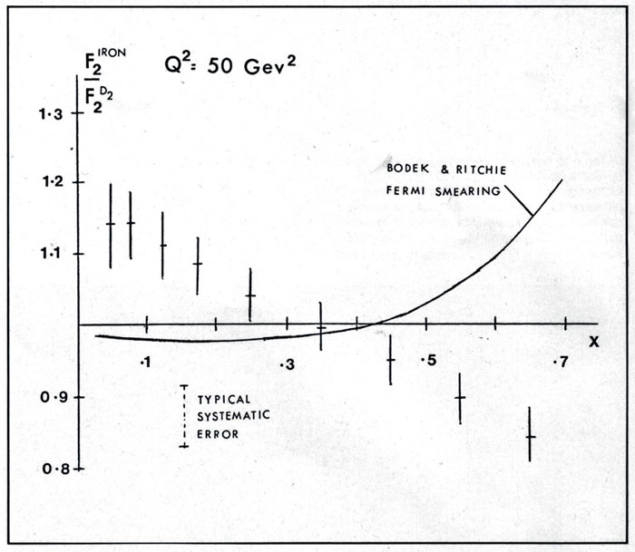

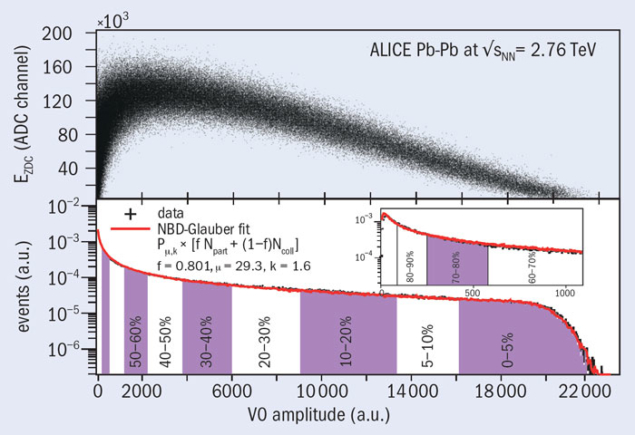

However, neither the impact parameter nor the number of participants, spectators or nucleon–nucleon collisions are directly measurable. This means that experimental observables are needed that can be related to these geometrical quantities. One such observable is the multiplicity of the particles produced in collision in a given rapidity range around mid-rapidity; this multiplicity increases monotonically with the impact parameter. A second useful observable is the energy carried by the spectators close to the beam direction and deposited – in the case of the ALICE experiment – in the Zero Degree Calorimeter (ZDC); this decreases for more central collisions, as shown in the upper part of figure 2.

Experimentally, centrality is expressed as a percentage of the total nuclear interaction cross-section, e.g. the 10% most central events are the 10% that have the highest particle multiplicity. But how much of the total nuclear cross-section is measured in ALICE? Are the events detected only hadronic processes or do they include something else?

The most peripheral events, 10% of the total, remain contaminated by electromagnetic processes and trigger inefficiency

ALICE collected data during the LHC’s periods of lead–lead running in 2010 and 2011 using interaction triggers that have an efficiency large enough to explore the entire sample of hadronic collisions. However, because of the strong electromagnetic fields generated as the relativistic heavy ions graze each other the event sample is contaminated by background from electromagnetic processes, such as pair-production and photonuclear interactions. These processes, which are characterized by low-multiplicity events with soft (low-momentum) particles close to mid-rapidity, produce events that are similar to peripheral hadronic collisions and must be rejected to isolate hadronic interactions. Part of the contamination is rejected by requiring that both nuclei break-up in the collision, producing a coincident signal in both sides of the ZDC. The remaining contamination is estimated using events generated by a Monte Carlo simulator of electromagnetic processes (e.g. STARLIGHT). This shows that for about 90% of the hadronic cross-section, the purity of the event sample and the efficiency of the event selection is 100%. Nevertheless the most peripheral events, 10% of the total, remain contaminated by electromagnetic processes and trigger inefficiency – and must be used with special care in the physics analyses.

The centrality of each event in the sample of hadronic interactions can be classified by using the measured particle multiplicity and the spectator energy deposited in the ZDC. Various detectors in ALICE measure quantities that are proportional to the particle multiplicity, with different detectors covering different regions in pseudo-rapidity (η). Several of these, e.g. the time-projection chamber (covering |Δη| < 0.8) the silicon pixel detector (|Δη| < 1.4), the forward multiplicity detector (1.7 < Δη < 5.0 and –3.4 < Δη < –1.7) and the V0 scintillators (2.8 < Δη < 5.1 and –3.7 < Δη < –1.7), are used to study how the centrality resolution depends on the acceptance and other possible detector effects (saturation, energy cut-off etc.). The percentiles of the hadronic cross-section are determined for any value of measured particle multiplicity (or something proportional to it, e.g. the V0 amplitude) by integrating the measured distribution, which can be divided into classes by defining sharp cuts that cor-respond to well defi ned percentile intervals of the cross-section, as indicated in the lower part of fi gure 2 for the V0 detectors.

Alternatively, measuring the energy deposited in the ZDC by the spectator particles in principle allows direct access to the number of participants (all of the nucleons minus the spectators). However, some spectator nucleons are bound into light nuclear fragments that, with a charge-to-mass ratio similar to that of the beam, remain inside the beam-pipe and are therefore undetected by the ZDC. This effect becomes quantitatively important for peripheral events because they have a large number of spectators, so the ZDC cannot be used alone to give a reliable estimate of the number of participants. Consequently, the information from the ZDC needs to be correlated to another quantity that has a monotonic relation with the participants. The ALICE collaboration uses the energy of the secondary particles (essentially photons produced by pion decays) measured by two small electromagnetic calorimeters (ZEM). Centrality classes are defined by cuts on the two-dimensional distribution of the ZDC energy as a function of the ZEM amplitude for the most central events (0–30%) above the point where the correlation between the ZDC and ZEM inverts sign.

So how can the events be partitioned? Should the process be based on 0–1% or 0–10% classes? And what is the best way to estimate the centrality? These questions relate to the issue of centrality resolution. The number of centrality classes that can be defined is connected to the resolution achieved by the centrality estimation. In general, centrality classes are defined so that the separation between the central values of the participant distributions for two adjacent classes is significantly larger than the resolution for the variable used for the classification.

The real resolution

In principle, the resolution is given by the difference between the true centrality and the value estimated using a given method. In reality, the true centrality is not known, so how can it be measured? ALICE tested its procedure on simulations using the event generator HIJING, which is widely used and tested on hadronic processes, together with a full-scale simulation of detector response based on the GEANT toolkit. In HIJING events, the value of the impact parameter for every given event and, hence, the true centrality is known. The full GEANT simulation yields the values of signals in the detectors for the given event, so using these centrality estimators an estimate of the centrality can be calculated. The real centrality resolution for the given event is equal to the difference between the measured and the true centrality.

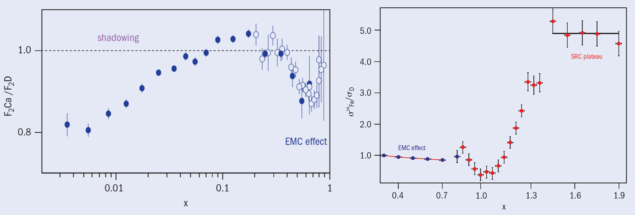

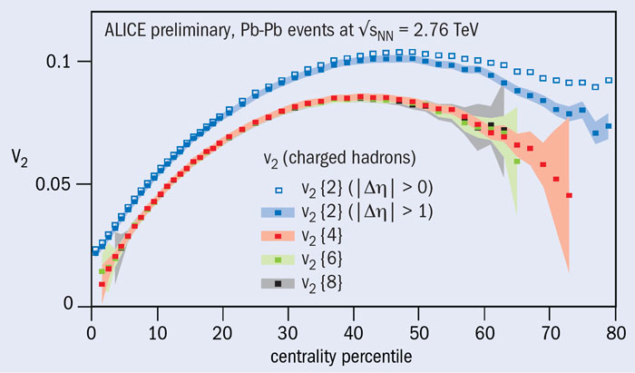

In the real data we approximated the true centrality in an iterative procedure, evaluating event-by-event the average centrality measured by all estimators. The correlation between various estimators is excellent, resulting in a high centrality-resolution. Since the resolution depends on the rapidity coverage of the detector used, the best result – achieved with the V0 detector, which has the largest pseudo-rapidity coverage in ALICE – ranges from 0.5% in central collisions to 2% in peripheral ones, in agreement with the estimation from simulations. This high resolution is confirmed by the analysis of elliptic flow and two-particle correlations where the results, which address geometrical aspects of the collisions, change with 1% centrality bins (figure 3).

So much for the experimental classification of the events in percentiles of the hadronic cross-section. This leaves one issue remaining: how to relate the experimental observables (particle multiplicity, zero-degree energy) to the geometry of the collision (impact parameter, Npart, Ncoll). What is the mean number of participants in the 10% most central events?

To answer this question requires a model. HIJING is not used in this case, because the simulated particle multiplicity does not agree with the measured one. Instead ALICE uses a much simpler model, the Glauber model. This is a simple technique, widely used in heavy-ion physics, from the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron at Brookhaven, to CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron, to Brookhaven’s Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collider. It uses few assumptions to describe heavy-ion collisions and couple the collision geometry to the detector signals. First, the two colliding nuclei are described by a realistic distribution of nucleons inside the nucleus measured in electron-scattering experiments (the Woods-Saxon distribution). Second, the nucleons are assumed to follow straight trajectories. Third, two nucleons from different nuclei are assumed to collide if their distance is less than the distance corresponding to the inelastic nucleon–nucleon cross-section. Last, the same cross-section is used for all successive collisions. The model, which is implemented in a Monte Carlo calculation, takes random samples from a geometrical distribution of the impact parameter and for each collision determines Npart and Ncoll.

The Glauber model can be combined with a simple model for particle production to simulate a multiplicity distribution that is then compared with the experimental one. The particle production is simulated in two steps. Employing a simple parameterization, the number of participants and the number of collisions can be used to determine the number of “ancestors”, i.e. independently emitting sources of particles. In the next step, each ancestor emits particles according to a negative binomial distribution (chosen because it describes particle multiplicity in nucleon–nucleon collisions). The simulated distribution describes up to 90% of the experimental one, as figure 2 shows.

Fitting the measured distribution (e.g. the V0 amplitude) with the distribution simulated using the Glauber model creates a connection between an experimental observable (the V0 amplitude) and the geometrical model of nuclear collisions employed in the model. Since the geometry information (b, Npart, Ncoll) for the simulated distribution is known from the model, the geometrical properties for centrality classes defined by sharp cuts in the simulated multiplicity distribution can be calculated.

The high-quality results obtained in the determination of centrality are directly reflected in the analyses that ALICE performs to investigate the properties of the system that strongly depend on its geometry. Elliptic flow, for example, is a fundamental measurement of the degree of collectivity of the system at an early stage of its evolution since it directly reflects the initial spatial anisotropy, which is largest at the beginning of the evolution. The quality of the centrality determination allows access to the geometrical properties of the system with a very high precision. To remove non-flow effects, which are predominantly short-ranged in rapidity, as well as artefacts of track-splitting, two-particle correlations are calculated in 1% centrality bins with a one-unit gap in pseudo-rapidity. Using these correlations, as well as the multi-particle cumulants (4th, 6th and 8th order), ALICE can extract the elliptic flow-coefficient v2 (figure 3), i.e. the second harmonic coefficient of the azimuthal Fourier decomposition of the momentum distribution (ALICE collaboration 2011). Such measurements have allowed ALICE to demonstrate that the hot and dense matter created in heavy-ion collisions at the LHC behaves like a fluid with almost zero viscosity (CERN Courier April 2011 p7) and to pursue further the hydrodynamic features of the quark–gluon plasma that is formed there.