The idea that the tunnel for the future Large Electron–Positron (LEP) collider should be able to house at some time even further in the future a Large Hadron Collider (LHC) was already in the air in the late 1970s. Moreover – thankfully – those leading CERN at the time had the vision to plan for a tunnel with a big enough diameter to allow the eventual installation of such an accelerator. In the broader community, however, enthusiasm for an LHC surfaced for the first time in 1984, promoted in part by members of CERN’s successful proton–antiproton collider experiments and their discovery of the W and Z bosons the previous year. A workshop in Lausanne on the “Large Hadron Collider in the LEP Tunnel” organized jointly by the European Committee for Future Accelerators (ECFA) and CERN brought together working groups that comprised machine experts, theorists and experimentalists.

With the realization of the great physics potential of an LHC, several motivating workshops and conferences followed where the formidable experimental challenges started to appear manageable, provided that enough R&D work on detectors could be carried out. Highlights of these “LHC experiment preliminaries” were the 1987 Workshop in La Thuile for the so-called “Rubbia Long-Range Planning Committee” and the large Aachen ECFA LHC Workshop in 1990. Last, in March 1992 the famous conference “Towards the LHC Experimental Programme” took place in Evian-les-Bains, where several proto-collaborations presented their designs in “expressions of interest”. Moreover, CERN’s LHC Detector R&D Committee (DRDC), which reviewed and steered R&D collaborations, greatly stimulated innovative developments in detector technology from the early 1990s.

Designs for a Higgs

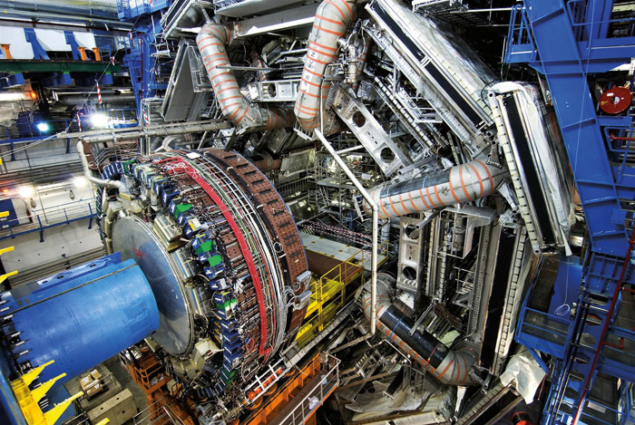

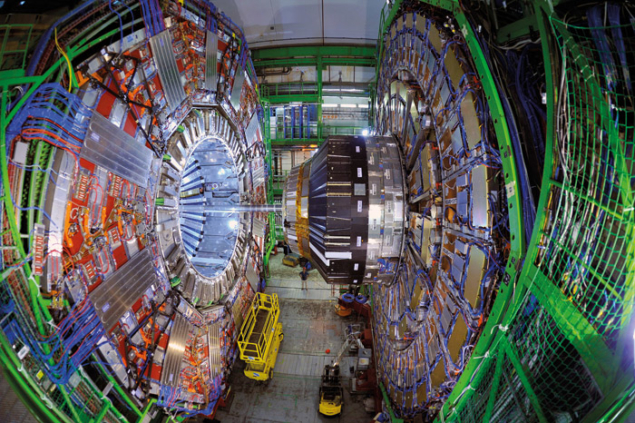

The detection of the Standard Model Higgs boson played a particularly important role in the design of the general-purpose experiments. In the region of low mass (114 < mH < 150 GeV), the two channels considered particularly suited for unambiguous discovery were the decay to two photons and the decay to two Z bosons, where one or both of the Z bosons could be virtual. Because the natural width of the putative Higgs boson is < 10 MeV, the width of any observed peak would be entirely dominated by instrumental mass-resolution. This meant that in designing the general-purpose detectors, considerable care was placed on the value of the magnetic-field strength, on the precision-tracking systems and on high-resolution electromagnetic calorimeters. The high-mass region and signatures from supersymmetry drove the need for good resolution for jets and missing transverse energy, as well as for almost full 4π calorimetry coverage.

The choice of the field configuration determined the overall design. It was well understood that to stand the best chance of making discoveries at the new “magic” energy scale of the LHC – and in the harsh conditions generated by about a billion pairs of protons interacting every second – would require the invention of new technologies while at the same time pushing existing ones to their limits. In fact, a prevalent saying was: “We think we know how to build a high-energy, high-luminosity hadron collider – but we don’t have the technology to build a detector for it.” That the general-purpose experiments have worked so marvellously well since the start-up of the LHC is a testament to the difficult technology choices made by the conceivers and the critical decisions made during the construction of these experiments. It is noteworthy that the very same elements mentioned above were crucial in the recent discovery of a Higgs boson.

At the Aachen meeting in 1990, much discussion took place on which detector technologies and field configurations to deploy. At the Evian meeting two years later, four experiment designs were presented: two using toroids and two using high-field solenoids. In the aftermath of this meeting, lively discussions took place in the community on how to continue and possibly join forces. The time remaining was short because the newly formed peer-review committee, the LHC Committee (LHCC), had set a deadline for the submission of the letters of intent (LoI) of 1 October 1992.

The designs based on the toroidal configurations merged to form the ATLAS experiment, deploying a superconducting air-core toroid for the measurement of muons, supplemented by a superconducting 2 T solenoid to provide the magnetic field for inner tracking and by a liquid-argon/lead electromagnetic calorimeter with a novel “accordion” geometry. The two solenoid-based concepts were eventually submitted separately. Although not spelt out explicitly, it was clear to everyone that resources would permit only two general-purpose experiments. It took seven rounds of intense encounters between the experiment teams and the LHCC referees before the committee decided at its 7th meeting on 8–9 June 1993 “to recommend provisionally that ATLAS and CMS should proceed to technical proposals”, with agreed milestones for further review in November 1993. The CMS design centred on a single large-bore, long, high-field superconducting solenoid, together with powerful microstrip-based inner tracking and an electromagnetic calorimeter of novel scintillating crystals.

So, the two general-purpose experiments were launched but the teams could not have foreseen the enormous technical, financial, industrial and human challenges that lay ahead. For the technical proposals, many difficult technology choices now had to be made “for real” for all of the detector components, whereas the LoI had just presented options for many items. This meant, for example, that several large R&D collaborations sometimes had to give up on excellent developments in instrumentation that had been carried out over many years and to find their new place working on the technologies that the experimental collaborations considered best able to deliver the physics. Costs and resources were a constant struggle: they were reviewed over a period of many years by an expert costs-review committee (called CORE) of the LHCC. It was not easy for many bright physicists to accept that the chosen technology also had to remain affordable.

The years just after the LoI were also the time when the two collaborations grew most rapidly in terms of people and institutes. Finding new collaborators was a high priority on the “to do” list of the spokespeople, who became real frequent-flyers, conducting global “grand tours”. These included many trips to far-flung, non-European countries to motivate and invite participation and contributions to the experiments, in parallel (and sometimes even in competition) with CERN’s effort to get non-member state contributions to enable the timely construction of the accelerator. It is during this period that the currently healthy mix of wealthy and less-wealthy countries was established in the two collaborations, clearly placing a value on not only material contributions but also intellectual ones. One important event was the integration of a strong US community after the discontinuation of the Superconducting Supercollider in 1993, which had a notable impact on both ATLAS and CMS in terms of the final capabilities of these experiments.

The submissions of the technical proposals followed in December 1994 and these were approved in 1996. The formal approval for construction was given on 1 July 1997 by the then director-general, Chris Llewellyn Smith, based on the recommendations of the Research Board and the LHCC (by then at meeting number 27) after the first of a long series of Technical Design Reports and the imposing of a material cost ceiling of SwFr475 million. These were also the years when the formal framework was set up by CERN and all of the funding agencies, first in interim and finally via a detailed Construction Memorandum of Understanding, agreed on in the new, biannual Resources Review Boards.

To explore all our coverage marking the 10th anniversary of the discovery of the Higgs boson ...