From 29 January to 1 February, the Chamonix Workshop 2024 upheld its long tradition of fostering open and collaborative discussions within CERN’s accelerator and physics communities. This year marked a significant shift with more explicit inclusion of the injector complex, acknowledging its crucial role in shaping future research endeavours. Chamonix discussions focused on three main areas: maximising the remaining years of Run 3; the High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC), preparations for Long Shutdown 3 and operations in Run 4; and a look to the further future and the proposed Future Circular Collider (FCC).

Immense effort

Analysing the performance of CERN’s accelerator complex, speakers noted the impressive progress to date, examined limitations in the LHC and injectors and discussed improvements for optimal performance in upcoming runs. It’s difficult to do justice to the immense technical effort made by all systems, operations and technical infrastructure teams that underpins the exploitation of the complex. Machine availability emerged as a crucial theme, recognised as critical for both maximising the potential of existing facilities and ensuring the success of the HL-LHC. Fault tracking, dedicated maintenance efforts and targeted infrastructure improvements across the complex were highlighted as key contributors to achieving and maintaining optimal uptime.

As the HL-LHC project moves into full series production, the technical challenges associated with magnets, cold powering and crab cavities are being addressed (CERN Courier January/February 2024 p37). Looking beyond Long Shutdown 3 (LS3), potential limitations are already being targeted now, with, for example, electron-cloud mitigation measures planned to be deployed in LS3. The transition to the high-luminosity era will involve a huge programme of work that requires meticulous preparation and a well-coordinated effort across the complex during LS3, which will see the deployment of the HL-LHC, a widespread consolidation effort, and other upgrades such as that planned for the ECN3 cavern at CERN’s North Area.

The vision for the next decades of these facilities is diverse, imaginative and well-motivated from a physics perspective

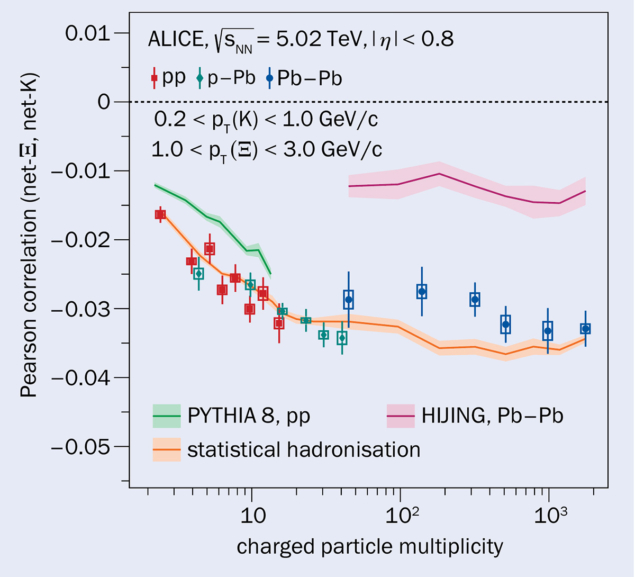

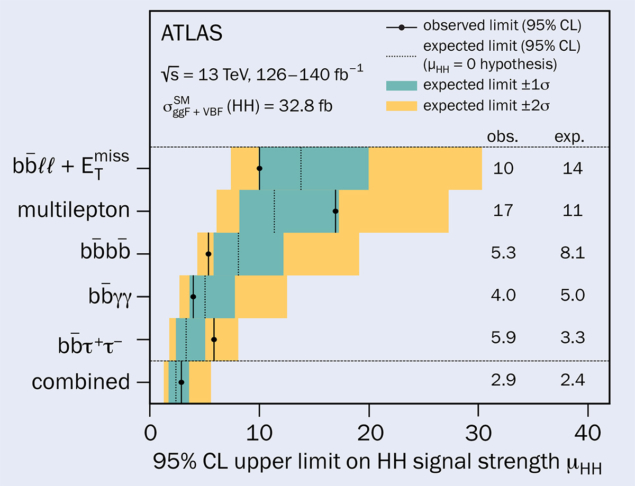

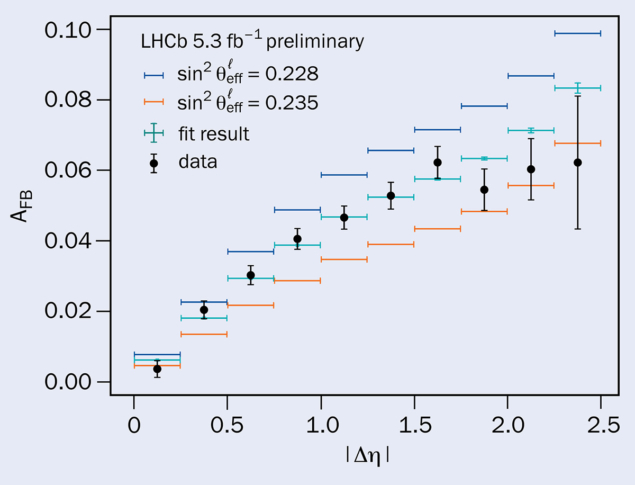

The breadth and depth of the physics being performed at CERN facilities is quite remarkable, and the Chamonix workshop reconfirmed the high demand from experimentalists across the board. The unique capabilities of ISOLDE, n_TOF, AD-ELENA, and the East and North Areas were recognised. The North Area, for example, provides protons, hadrons, electrons and ion beams for detector R&D, experiments, the CERN neutrino platform, irradiation facilities and counts more than 2000 users. The vision for the next decades of these facilities is diverse, imaginative and well-motivated from a physics perspective. The potential for long-term exploitation and leveraging fully the capabilities of the LHC and other facilities is considerable, demanding continued support and development.

In the longer term, CERN is exploring the potential construction of the FCC via a dedicated feasibility study that has just delivered a mid-term report – a summary of which was presented at Chamonix. The initiative is accompanied by R&D on key accelerator technologies. The physics case for FCC-ee was well made for an audience of mostly non-particle physicists, concluding that the FCC is the only proposed collider that covers each key area in the field – electroweak, QCD, flavour, Higgs and searches for phenomena beyond the Standard Model – in paradigm-shifting depth.

Environmental consciousness

Sustainability was another focus of the Chamonix workshop. Building and operating future facilities with environmental consciousness is a top priority, and full life-cycle analyses will be performed for any options to help ensure a low-carbon future.

Interesting times, lots to do. To quote former CERN Director-General Herwig Schopper from 1983: “It is therefore clear that, for some time to come, there will be interesting work to do and I doubt whether accelerator experts will find themselves without a job.”