Image credit: Luca Nagel/CAST.

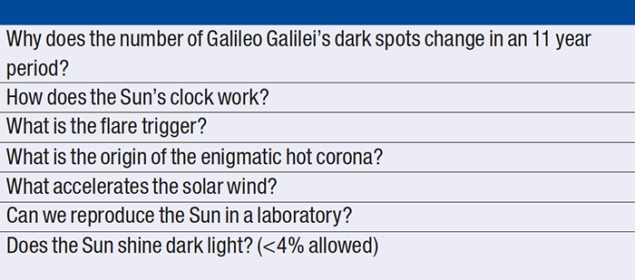

Our star has been the target of human investigation since the beginning of science. However, a plethora of observations are not yet understood. A good example is the unnaturally hot solar corona, the temperature of which spans 1–10 MK. This anomaly has been studied since 1939 but, in spite of a tremendous number of observations, no real progress in understanding its origin has been made. We also know that a significant fraction of the Sun’s total luminosity, about 4%, can escape as some form of radiation that we do not yet know, without being in conflict with the constraints imposed by the evolution of the Sun. In this framework, physicists have hypothesised the existence of exotic particles, including axions and chameleons. Other particles, such as the celebrated WIMPs, also point to the Sun as a target for relevant investigations. Indeed, over cosmic time periods, WIMPs can be gravitationally trapped inside the solar core. There, they condense, allowing their mutual annihilation into known particles, including escaping high-energy neutrinos.

A breakthrough discovery in the so-called “dark sector” could pop up at any time. The question is when this will happen and where: in an Earth-bound laboratory or in a space-bound one. It is worth stressing that it is not at all obvious whether the extreme conditions in the Sun can be completely duplicated on Earth.

Benchmark for axion searches

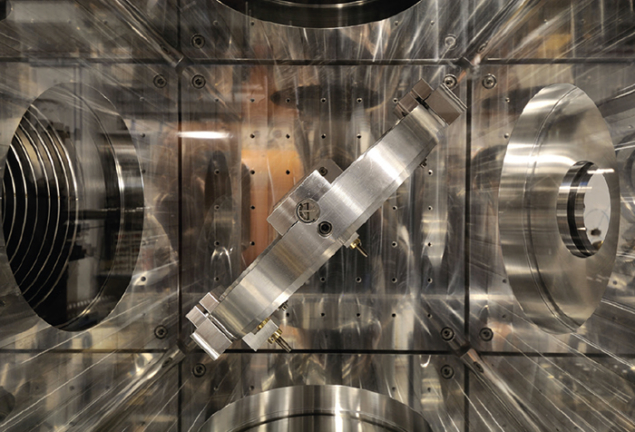

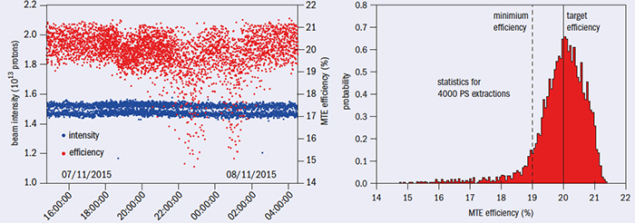

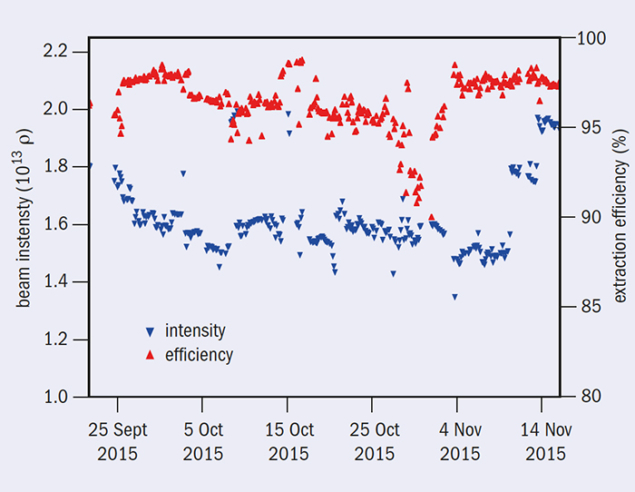

For many days in recent years, CAST – the CERN Axion Solar Telescope (CERN Courier April 2010 p22) – has pointed its antenna towards the Sun for about 100 minutes during sunrise and sunset. Its aim was to detect solar axions through the Primakoff effect (1950), a classic detection scheme from particle physics. This solar-axion search was completed in November 2015 (CERN Bulletin, https://cds.cern.ch/journal/CERNBulletin/2015/39/News%20Articles/2053133?ln=en), and even though CAST has not observed an axion signature, it provides world-best limits on the axion interaction strength with normal matter in the form of the magnetic field present inside the CAST magnet bores.

Image credit: CAPP, Korea.

The results of the CAST scientific programme were also achieved thanks to the X-ray telescope (XRT) recovered from the ABRIXAS German space mission and installed downstream on one of the magnet bores. The telescope works as a lens focusing the photon flux onto the detector. Any increase in the signal-to-noise ratio would be a signature of axions. This unique technique, borrowed from astrophysics, allowed the collaboration to simultaneously measure signal and background. Given its success, a second X-ray telescope was added in 2014.

Very accurate tracking of the Sun is crucial to the experiment’s data analysis. To provide this, CERN surveyors pinpoint exactly where the telescope lies and where it is pointing to, relative to a reference in time and space. However, to be absolutely certain, twice a year, when the Sun is visible through a window in the CAST experimental hall, the magnet tracks the Sun with a camera mounted and aligned to point exactly along its axis. This process of “Sun filming” has confirmed that CAST is pointing at the centre of the Sun with sufficient precision.

Up to now, CAST has been looking for exotica that the Sun might have produced some 10 minutes earlier. However, thanks to a continuous upgrade programme for the detectors and the development of new ideas, the collaboration is now extending its horizons, back in time closer to the Big Bang and into the dark sector. In its 119th meeting, the CERN SPS and PS experiments Committee (SPSC) recommended the new CAST physics programme for approval, which includes searches for relic axions and chameleons.

Axions from the Big Bang

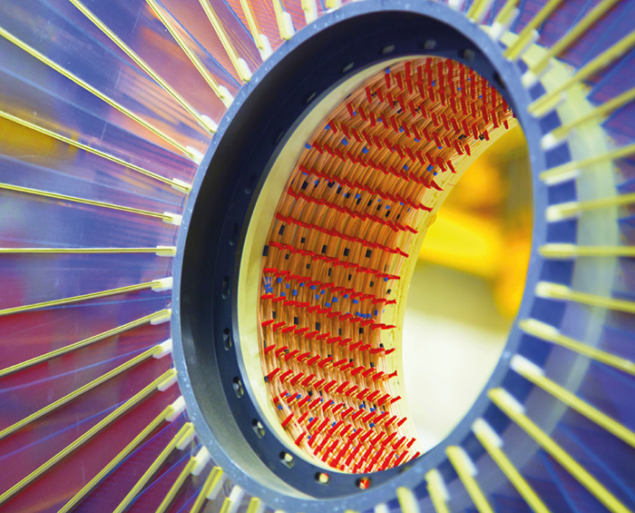

Due to their extremely long lifetime (longer than the age of the universe), axions produced during the Big Bang could still be detected today. These relic particles have been searched for with instruments using a resonant cavity immersed in a strong magnetic field where axions are expected to convert into photons (with a probability that depends quadratically on the magnetic-field intensity). The signal is further enhanced when the cavity is at resonance with the photon frequency. In particular, the signal strength depends on the cavity “quality factor”, defined as the ratio between the cavity fundamental frequency and the resonance line width.

However, the inherent problem of axion searches is the unknown rest mass, although the cosmologically preferred mass range for the so-called cold dark-matter axions lies between μeV/c2 and meV/c2, with a favoured region around 0.1 meV. The photon energy is equal to the axion rest mass, because its kinetic energy is negligibly small. To scan the regions of interest, the cavity resonant frequency is varied over a certain axion-mass range, basically determined by cavity size and shape.

Image credit: Giovanni Cantatore.

Dipole magnets, such as the CAST magnet, can be transformed into relic axion antennas by means of new resonant microwave cavities. These cavities, designed and built by the Korean Centre for Axion and Precision Physics (CAPP) in collaboration with CERN, will be inserted inside the dipole magnetic field within the 1.7 K cold bores to search for microwave photons converted from cosmological axions, which would be direct messengers from the Big Bang era. In addition, a second microwave sensor will be inserted in the other bore. With its new set-up currently under construction, CAST should have access to an axion-mass range up to 100 μeV/c2. At these relatively high mass values, detection becomes much harder, but the hope is that this region, which is critical for the dark-matter conundrum, will also be explored.

Chameleons come on stage

As may be imagined, detecting chameleons – new scalar particles that are possible candidates for the unknown dark energy – is not a trivial matter. The CAST collaboration plans to do it by exploiting two different couplings: Primakoff coupling to photons and direct coupling to matter.

The expected energy spectrum of solar chameleons has a peak at about 600 eV, making it even harder to detect them through their Primakoff coupling than the axions. Therefore, sub-keV threshold, low-background photon detectors are required. To tackle this problem, the CAST collaboration decided to start with a Silicon Drift Detector (SDD), becoming, with recently published results, the first chameleon helioscope. The new InGRID detector, based on the MicroMegas concept and having on-board read-out electronics, replaced the CCD camera in the XRT focal plane in 2014, improving the overall expected performance of CAST for solar chameleons.

Chameleon particles are theorised to have amazing properties: they can freely traverse thick slabs of dense matter if they impinge on them normally (i.e. perpendicular to), or they can bounce off nanometre-thin membranes, not much denser than ordinary glass, when approaching them at a grazing incidence angle of just a few degrees. In doing so, they exert a minute force, much like grains of sand hitting the palm of a hand. If detected, this tiny force is the signature of the direct interaction of chameleons with matter.

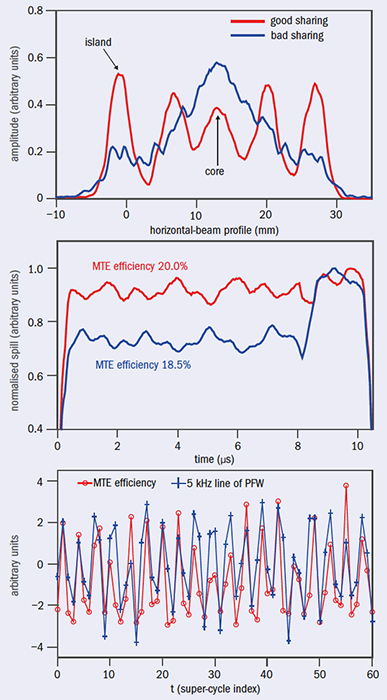

Forces are experienced in everyday life, so there may seem to be nothing special about detecting them. However, sensing exceedingly tiny forces requires advanced skills and techniques. The KWISP opto-mechanical force sensor is able to instantaneously feel forces of 10–14 N – that is, the weight of a single bacterium. It uses a Si3N4 membrane, just 100 nm thick, to intercept the flux of solar chameleons. Being as elastic as a drumhead, it flexes under their collective force (pressure) by an amount less than the size of an atomic nucleus. The membrane sits inside a Fabry–Pérot optical resonator, made of two high-reflectivity super mirrors facing each other, where a standing wave from an IR laser beam is trapped. As the membrane flexes, the characteristic frequency of this wave changes, generating the signal. The power of the KWISP sensor comes from the combined response of two high-Q resonators, the optical (Fabry–Perot) and the mechanical (membrane).

In addition to KWISP, a further ingredient is necessary in the search for chameleons: a time-dependent amplitude modulation on the chameleon flux in such a way as to beat the drum at its eigenfrequency for maximum effect. To solve this problem, the authors have invented the chameleon chopper, which is basically a rotating optically flat surface, applying the principle of chameleon optics: transmission at normal incidence, reflection at grazing incidence. Surprisingly, phase-locking techniques can also exploit this angular variation to obtain additional information on chameleon physics.

According to theory, the internal surfaces of the ABRIXAS telescope, designed to reflect X-rays impinging at grazing incidence, would also reflect and focus chameleons. This increases their flux by a factor larger than 100, which is further enhanced by the exposure time gained from Sun-tracking. This unplanned ability of the X-ray telescope is one of those lucky events by which nature sometimes smiles at scientists, allowing them to explore its secrets.

The KWISP prototype is currently taking data at INFN Trieste (Italy) and a clone is being commissioned at CERN to take advantage of the CAST infrastructure. As mentioned also by the SPSC referees, with the force-sensor KWISP, it should be possible to address more fundamental physics questions, such as quantum gravity or the validity of Newton’s 1/R2 law at short distances. We plan, with colleagues from the Technical University in Darmstadt (Germany), Freiburg University (Germany) and CAPP (Korea), to develop an advanced KWISP design, aKWISP, and we welcome the interest of additional collaborators.

While it remains one of the lowest-cost astroparticle physics experiments, CAST is preparing to leap further into the dark sector. As history teaches us (see table 1), the Sun may be the key to this, although as our understanding of the Sun deepens, we will most probably uncover more mysteries about the star that gives us life.

• For more information, see https://cds.cern.ch/record/2022893.