Quarks contribute less than 1% to the mass of protons and neutrons. This provokes an astonishing question: where does the other 99% of the mass of the visible universe come from? The answer lies in the gluon, and how it interacts with itself to bind quarks together inside hadrons.

Much remains to be understood about gluon dynamics. At present, the chief experimental challenge is to observe the onset of gluon saturation – a dynamic equilibrium between gluon splitting and recombination predicted by QCD. The experimental key looks likely to be a rare but intriguing type of LHC interaction known as an ultraperipheral collision (UPC), and the breakthrough may come as soon as the next experimental run.

Gluon saturation is expected to end the rapid growth in gluon density measured at the HERA electron–proton collider at DESY in the 1990s and 2000s. HERA observed this growth as the energy of interactions increased and as the fraction of the proton’s momentum borne by the gluons (Bjorken x) decreased.

So gluons become more numerous in hadrons as their energy decreases – but to what end?

Gluonic hotspots are now being probed with unprecedented precision at the LHC and are central to understanding the high-energy regime of QCD

Nonlinear effects are expected to arise due to processes like gluon recombination, wherein two gluons combine to become one. When gluon recombination becomes a significant factor in QCD dynamics, gluon saturation sets in – an emergent phenomenon whose energy scale is a critical parameter to determine experimentally. At this scale, gluons begin to act like classical fields and gluon density plateaus. A dilute partonic picture transitions to a dense, saturated state. For recombination to take precedence over splitting, gluon momenta must be very small, corresponding to low values of Bjorken x. The saturation scale should also be directly proportional to the colour-charge density, making heavy nuclei like lead ideal for studying nonlinear QCD phenomena.

But despite strong theoretical reasoning and tantalising experimental hints, direct evidence for gluon saturation remains elusive.

Since the conclusion of the HERA programme, the quest to explore gluon saturation has shifted focus to the LHC. But with no point-like electron to probe the hadronic target, LHC physicists had to find a new point-like probe: light itself. UPCs at the LHC exploit the flux of quasi-real high-energy photons generated by ultra-relativistic particles. For heavy ions like lead, this flux of photons is enhanced by the square of the nuclear charge, enabling studies of photon-proton (γp) and photon-nucleus interactions at centre-of-mass energies reaching the TeV scale.

Keeping it clean

What really sets UPCs apart is their clean environment. UPCs occur at large impact parameters well outside the range of the strong nuclear force, allowing the nuclei to remain intact. Unlike hadronic collisions, which can produce thousands of particles, UPCs often involve only a few final-state particles, for example a single J/ψ, providing an ideal laboratory for gluon saturation. J/ψ are produced when a cc pair created by two or more gluons from one nucleus is brought on-shell by interacting with a quasi-real photon from the other nucleus (see “Sensitivity to saturation” figure).

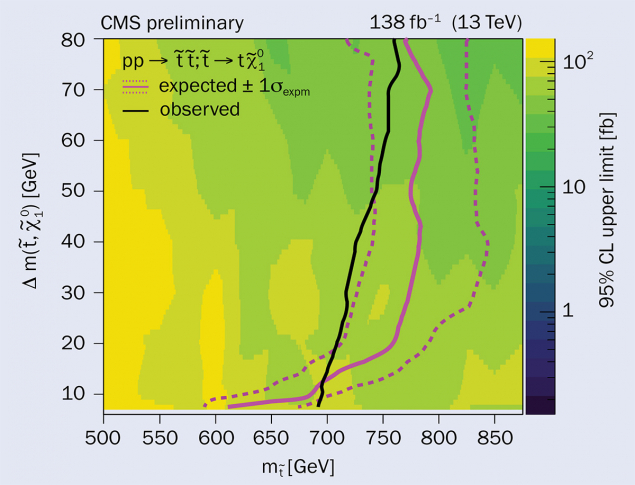

Gluon saturation models predict deviations in the γp → J/ψp cross section from the power-law behaviour observed at HERA. The LHC experiments are placing a significant focus on investigating the energy dependence of this process to identify potential signatures of saturation, with ALICE and LHCb extending studies to higher γp centre-of-mass energies (Wγp) and lower Bjorken x than HERA. The results so far reveal that the cross-section continues to increase with energy, consistent with the power-law trend (see “Approaching the plateau?” figure).

The symmetric nature of pp collisions introduces significant challenges. In pp collisions, either proton can act as the photon source, leading to an intrinsic ambiguity in identifying the photon emitter. In proton–lead (pPb) collisions, the lead nucleus overwhelmingly dominates photon emission, eliminating this ambiguity. This makes pPb collisions an ideal environment for precise studies of the photoproduction of J/ψ by protons.

During LHC Run 1, the ALICE experiment probed Wγp up to 706 GeV in pPb collisions, more than doubling HERA’s maximum reach of 300 GeV. This translates to probing Bjorken-x values as low as 10–5, significantly beyond the regime explored at HERA. LHCb took a different approach. The collaboration inferred the behaviour of pp collisions at high energies (“W+ solutions”) by assuming knowledge of their energy dependence at low energies (“W- solutions”), allowing LHCb to probe gluon energies as small as 10–6 in Bjorken x and Wγp up to 2 TeV.

There is not yet any theoretical consensus on whether LHC data align with gluon-saturation predictions, and the measurements remain statistically limited, leaving room for further exploration. Theoretical challenges include incomplete next-to-leading-order calculations and the reliance of some models on fits to HERA data. Progress will depend on robust and model-independent calculations and high-quality UPC data from pPb collisions in LHC Run 3 and Run 4.

Some models predict a slowing increase in the γp → J/ψp cross section with energy at small Bjorken x. If these models are correct, gluon saturation will likely be discovered in LHC Run 4, where we expect to see a clear observation of whether pPb data deviate from the power law observed so far.

Gluonic hotspots

If a UPC photon interacts with the collective colour field of a nucleus – coherent scattering – it probes its overall distribution of gluons. If a UPC photon interacts with individual nucleons or smaller sub-nucleonic structures – incoherent scattering – it can probe smaller-scale gluon fluctuations.

These fluctuations, known as gluonic hotspots, are theorised to become more numerous and overlap in the regime of gluon saturation (see “Onset of saturation” figure). Now being probed with unprecedented precision at the LHC, they are central to understanding the high-energy regime of QCD.

Gluonic hotspots are used to model the internal transverse structure of colliding protons or nuclei (see “Hotspot snapshots” figure). The saturation scale is inherently impact-parameter dependent, with the densest colour charge densities concentrated at the core of the proton or nucleus, and diminishing toward the periphery, though subject to fluctuations. Researchers are increasingly interested in exploring how these fluctuations depend on the impact parameter of collisions to better characterise the spatial dynamics of colour charge. Future analyses will pinpoint contributions from localised hotspots where saturation effects are most likely to be observed.

The energy dependence of incoherent or dissociative photoproduction promises a clear signature for gluon saturation, independent of the coherent power-law method described above. As saturation sets in, all gluon configurations in the target converge to similar densities, causing the variance of the gluon field to decrease, and with it the dissociative cross section. Detecting a peak and a decline in the incoherent cross-section as a function of energy would represent a clear signature of gluon saturation.

The ALICE collaboration has taken significant steps in exploring this quantum terrain, demonstrating the possibility of studying different geometrical configurations of quantum fluctuations in processes where protons or lead nucleons dissociate. The results highlight a striking correlation between momentum transfer, which is inversely proportional to the impact parameter, and the size of the target structure. The observation that sub-nucleonic structures impart the greatest momentum transfer is compelling evidence for gluonic quantum fluctuations at the sub-nucleon level.

Into the shadows

In 1982 the European Muon Collaboration observed an intriguing phenomenon: nuclei appeared to contain fewer gluons than expected based on the contributions from their individual protons and neutrons. This effect, known as nuclear shadowing, was observed in experiments conducted at CERN at moderate values of Bjorken x. It is now known to occur because the interaction of a probe with one gluon reduces the likelihood of the probe interacting with other gluons within the nucleus – the gluons hiding behind them, in their shadow, so to speak. At smaller values of Bjorken x, saturation further suppresses the number of gluons contributing to the interaction.

The relationship between gluon saturation and nuclear shadowing is poorly understood, and separating their effects remains an open challenge. The situation is further complicated by an experimental reliance on lead–lead (PbPb) collisions, which, like pp collisions, suffer from ambiguity in identifying the interacting nucleus, unless the interaction is accompanied by an ejected neutron.

The ALICE, CMS and LHCb experiments have extensively studied nuclear shadowing via the exclusive production of vector mesons such as J/ψ in ultraperipheral PbPb

collisions. Results span photon–nucleus collision energies from 10 to 1000 GeV. The onset of nuclear shadowing, or another nonlinear QCD phenomenon like saturation, is clearly visible as a function of energy and Bjorken x (see “Nuclear shadowing” figure).

Multidimensional maps

While both saturation-based and gluon shadowing models describe the data reasonably well at high energies, neither framework captures the observed trends across the entire kinematic range. Future efforts must go beyond energy dependence by being differential in momentum transfer and studying a range of vector mesons with complementary sensitivities to the saturation scale.

Soon to be constructed at Brookhaven National Laboratory, the Electron-Ion Collider (EIC) promises to transform our understanding of gluonic matter. Designed specifically for QCD research, the EIC will probe gluon saturation and shadowing in unprecedented detail, using a broad array of reactions, collision species and energy levels. By providing a multidimensional map of gluonic behaviour, the EIC will address fundamental questions such as the origin of mass and nuclear spin.

Before then, a tenfold increase in PbPb statistics in LHC Runs 3 and 4 will allow a transformative leap in low Bjorken-x physics. Though not originally designed for low Bjorken-x physics, the LHC’s unparalleled energy reach and diverse range of colliding systems offers unique opportunities to explore gluon dynamics at the highest energies.

Enhanced capabilities

Surpassing the gains from increased luminosity alone, ALICE’s new triggerless detector readout mode will offer a vast improvement over previous runs, which were constrained by dedicated triggers and bandwidth limitations. Subdetector upgrades will also play an important role. The muon forward tracker has already enhanced ALICE’s capabilities, and the high-granularity forward calorimeter set to be installed in time for Run 4 is specifically designed to improve sensitivity to small Bjorken-x physics (see “Saturation specific” figure).

Ultraperipheral-collision physics at the LHC is far more than a technical exploration of QCD. Gluons govern the structure of all visible matter. Saturation, hotspots and shadowing shed light on the origin of 99% of the mass of the visible universe.