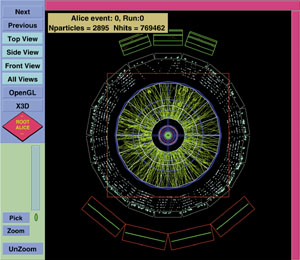

Imagine trying to record a symphony in a second. That is effectively what CERN’s ALICE collaboration will have to do when the laboratory’s forthcoming Large Hadron Collider (LHC) starts up in 2005. Furthermore, that rate will have to be sustained for a full month each year.

ALICE is the LHC’s dedicated heavy-ion experiment. Although heavy-ion running will occupy just one month per year, the huge number of particles produced in ion collisions means that ALICE will record as much data in that month as the ATLAS and CMS experiments plan to do during the whole of the LHC annual run. The target is to store one petabyte (1015 bytes) per year, recorded at the rate of more than 1 Gbyte/s. This is the ALICE data challenge, and it dwarfs existing data acquisition (DAQ) applications. At CERN’s current flagship accelerator LEP, for example, data rates are counted in fractions of 1 Mbyte/s. Even NASA’s Earth Observing System, which will monitor the Earth day and night, will take years to produce a petabyte of data.

Meeting the challenge is a long-term project, and work has already begun. People from the ALICE collaboration have been working with members of CERN’s Information Technology Division to develop the experiment’s data acquisition and recording systems. Matters are further complicated by the fact that the ALICE experiment will be situated several kilometres away from CERN’s computer centre, where the data will be recorded. This adds complexity and makes it even more important to start work now.

Standard components – such as CERN’s network backbone and farms of PCs running the Linux operating system – will be used to minimize capital outlay. They will, however, be reconfigured for the task in order to extract the maximum performance from the system. Data will be recorded by StorageTek tape robots installed as part of the laboratory’s tape-automation project to pave the way for handling the large number of tapes that will be required by LHC experiments.

The first goal for the ALICE data challenge was to run the full system at a data transfer rate of 100 Mbyte/s – 10% of the final number. This was scheduled for March and April 2000 so as not to interfere with CERN’s experimental programme, which will get up to speed in the summer.

Data sources for the test were simulated ALICE events from a variety of locations at CERN. After being handled by the ALICE DAQ system (DATE) they were formatted by the ROOT software, developed by the global high energy physics community. The data were then sent through the CERN network to the computer centre, where two mass storage systems were put through their paces for two weeks each. The first, HPSS, is the fruit of a collaboration between industry and several US laboratories. The second, CASTOR, has been developed at CERN.

Although each component of the system had been tested individually and shown to work with high data rates, this year’s tests have demonstrated the old adage that the whole is frequently greater than the sum of its parts: problems only arose when all of the component systems were integrated.

The tests initially achieved a data rate of 60 Mbyte/s with the whole chain running smoothly. However, then problems started to appear in the Linux operating system used in the DAQ system’s PC farms. Because Linux is not a commercial product, the standard way of getting bugs fixed is to post a message on the Linux newsgroups. However, no-one has previously pushed Linux so hard, so solutions were not readily forthcoming and the team had to work with the Linux community to find their own.

That done, the rate was cranked up and failures started to occur in one of the CERN network’s many data switches. These were soon overcome – thanks this time to an upgrade provided by the company that built the switches – and the rate was taken up again. Finally the storage systems had trouble absorbing all of the data. When these problems were ironed out, the target peak rate of 100 Mbyte/s was achieved for short periods.

At the end of April the ALICE data challenge team had to put their tests on hold, leaving the CERN network and StorageTek robots at the disposal of ongoing experiments and test beams. During the tests, more than 20 Tbyte of data – equivalent to some 2000 standard PC hard disks – had been stored. The next milestone, scheduled for 2001, is to run the system at 100 Mbyte/s in a sustained way before increasing the rate, step by step, towards the final goal of 1 Gbyte/s by 2005. The ALICE data challenge team may not yet have made a symphony, but the overture is already complete.