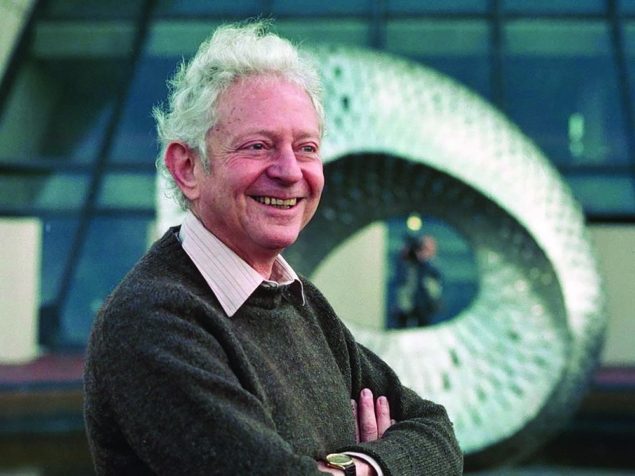

Leon Lederman, a pioneering US experimental particle physicist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery of the muon neutrino, passed away on 3 October at the age of 96. Lederman’s career spanned more than 60 years and had a major impact in putting the Standard Model of particle physics on empirical ground.

Lederman was born in New York City on 15 July 1922 to Russian–Jewish immigrant parents. He graduated from City College of New York with a degree in chemistry in 1943, but had already fallen under the influence of future physicists including Isaac Halpern and Martin Klein. After graduating he spent three years in the US Army, where he rose to the rank of 2nd lieutenant in the signal corps. In 1946 he entered the graduate school of physics at Columbia University, chaired by I I Rabi, and in 1951 he received his PhD in particle physics.

During the 1950s Lederman contributed to two major physics results: the discovery of the long-lived neutral K meson at Brookhaven National Laboratory’s 3 GeV Cosmotron in 1956; and, in 1957, the observation of parity violation in the pion–muon–electron decay chain at the Nevis 385 MeV synchrocyclotron at Columbia University. The latter experiment provided the first measurement of the muon magnetic moment, opening a path to the “g-2” experiment at CERN’s first accelerator, the synchrocyclotron. In 1958, shortly after he was promoted to professor, Lederman took his first sabbatical at CERN where he contributed to the organisation of the g-2 experiment. This programme lasted for almost two decades and involved many prominent CERN physicists, including Georges Charpak, Emilio Picasso, Francis Farley, Johannes Sens and Antonino Zichichi.

Lederman’s crowning achievement came in 1962 with the co-discovery of the muon neutrino at Brookhaven’s Alternating Gradient Synchrotron (AGS). For this work, he shared the 1988 Nobel Prize in Physics with Jack Steinberger and the late Melvin Schwartz “for the neutrino beam method and the demonstration of the doublet structure of the leptons through the discovery of the muon neutrino.” The experiment used a spark chamber to show that the neutrinos from beta decay and the neutrinos from muon decay were different, leading to the first direct observation of muon neutrinos and marking a key step in the understanding of weak interactions. Steinberger, who joined CERN six years after the muon-neutrino discovery and is now 97, has fond memories of his collaboration with Lederman. “What I remember about Leon is that we worked together at the same labs, at Nevis and at Brookhaven, and we got the Nobel Prize together, with Mel Schwartz. It was for a non-trivial experiment. He was a good friend. I’m very sad that he’s gone.”

At the end of the 1960s, in another experiment at the AGS, Lederman discovered the production of muon pairs with a continuous mass distribution in proton–nucleon collisions – an unexpected phenomenon that was soon interpreted as the result of quark–antiquark annihilation. As a follow-up to this experiment, in collaboration with physicists from CERN, Columbia and Rockefeller universities, Lederman proposed to study the production of electron–positron pairs at CERN’s Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR), which started operation in 1971. The experiment, known as R-103, discovered the production of neutral pions at high transverse momentum with a yield several orders of magnitude larger than expected. The result was again interpreted in terms of hard collisions between point-like proton constituents, demonstrating that these constituents also feel the strong interaction. “I had the privilege of working with Leon at Columbia in 1969–1970, when the R-103 experiment was proposed, and during the first years of ISR operation when he came to CERN,” says Luigi Di Lella of CERN. “I remember Leon as a physicist with enormous imagination, a boundless source of stimulating and often unconventional new ideas, which he always presented in a friendly and joyful atmosphere.”

As leader of the E70 and E288 experiments at Fermilab in the 1970s, Lederman also drove the effort that led to the discovery of the upsilon, the bound state of a bottom quark and antiquark, in 1977 (CERN Courier June 2017 p35). But his influence on the field of particle physics permeates far beyond his specific areas of research. In particular, he was a passionate advocate of education and worked with government and schools to create opportunities for students and better integrate physics into public education. He also had the rare quality to not take himself too seriously. Concerning the Higgs boson, he famously coined the term “God Particle” by using it in the title of his 1993 popular-science book The God Particle: If the Universe Is the Answer, What Is the Question? – though legend has it that he had originally wanted to call it the “God-dammed particle” because the Higgs boson was so difficult to find.

Lederman was director of the Nevis Laboratories at Columbia from 1961 to 1978. In 1979 he became director of Fermilab, where his vision and strategic planning led to the construction of the Tevatron (which operated from 1987 to 2011 and was the world’s highest-energy accelerator before the Large Hadron Collider came along). He stepped down as Fermilab director in 1989 and joined the faculty of the University of Chicago and, later, the Illinois Institute of Technology.

“Leon Lederman provided the scientific vision that allowed Fermilab to remain on the cutting edge of technology for more than 40 years,” says Nigel Lockyer, Fermilab’s current director. “Leon’s leadership helped to shape the field of particle physics, designing, building and operating the Tevatron and positioning the laboratory to become a world leader in accelerator and neutrino science. Leon had an immeasurable impact on the evolution of our laboratory and our commitment to future generations of scientists, and his legacy will live on in our daily work and our outreach efforts.”