Materials exposed to the high-energy beams in a particle accelerator must fulfil a demanding checklist of mechanical, electrical and vacuum requirements. While the structural function comes from the bulk materials, many other properties are ascribed to a thin surface layer, sometimes just a few tens of nanometres thick. This is typically the case for the desorption caused by electron, photon and ion collisions; Joule-effect heating induced by the electromagnetic field associated with the particle beams; and electron multipacting phenomena (see “Collaboration yields vacuum innovation”). To deliver the required performance, dedicated chemical and electrochemical treatments are needed – and more often than not mandatory – to re-engineer the physical and chemical properties of vacuum component/subsystem surfaces.

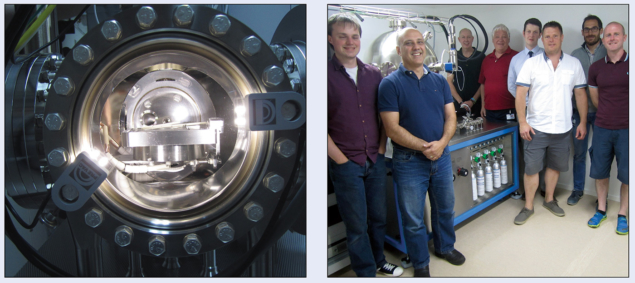

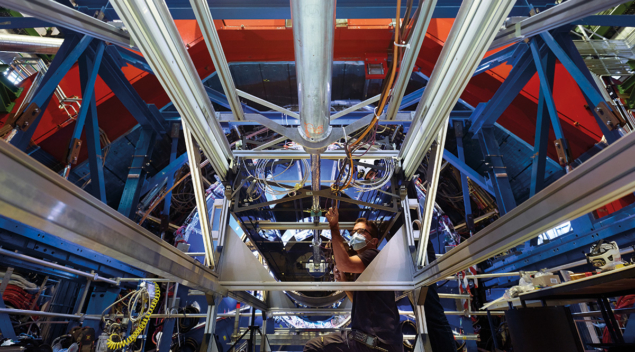

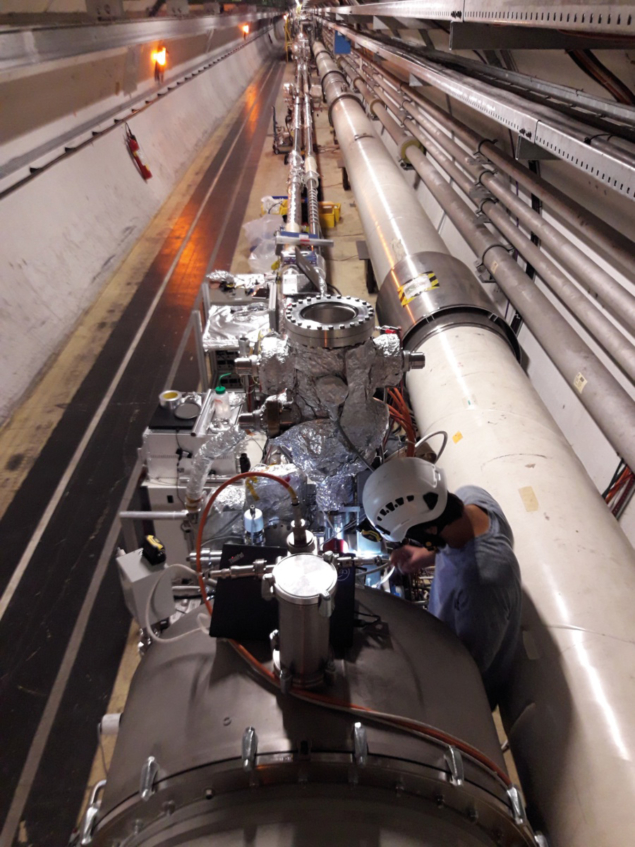

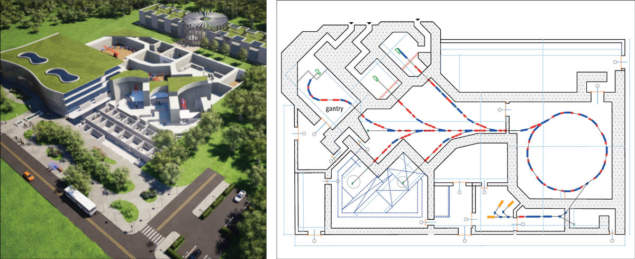

The bigger drivers here are the construction and operation of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and the High-Luminosity LHC upgrade – projects that, in turn, have driven impressive developments in CERN’s capabilities and infrastructure for surface chemistry and surface modification. The most visible example of this synergy is the new Building 107, a state-of-the-art facility that combines a diverse portfolio of chemical and electrochemical surface treatments with a bulletproof approach to risk management for personnel and the environment. Operationally, that ability to characterise, re-engineer and fine-tune surface properties has scaled dramatically over the last decade, spurred by the recruitment of a world-class team of scientists and engineers, the purchase of advanced chemical processing systems, and the consolidation of our R&D collaborations with specialist research institutes across Europe.

Chemistry in action

Within CERN’s Building 107, an imposing structure located on the corner of Rue Salam and Rue Bloch, the simplest treatment to implement – as well as the most common – is chemical surface cleaning. After machining and handling, any accelerator component will be contaminated by a layer of dirt – mainly organic products, dust and salts. Successful cleaning requires the right choice of materials and production strategy. A typical error in the design of vacuum components, for example, is the presence of surfaces that are hidden (and so difficult to clean) or holes that cannot be rinsed or dried fully. Standard cleaning methods to tackle such issues are based on detergents that, in aqueous solution, will lower the surface tensions and so aid the rinsing of foreign materials like grease and dust.

Successful cleaning requires the right choice of materials and production strategy

The nature of the accelerator materials means there are also secondary effects of cleaning that must be considered at the design phase – e.g. removal of the oxide layer (pickling) for copper and etching for aluminium alloys. To improve the cleaning process, we apply mechanical agitation via circulation of cleaning fluids, oscillation of components and ultrasonic vibration. The last of these creates waves at a frequency higher than 25 kHz. In the expansion phase of the liquid waves, microbubbles of vapour are generated (cavitation), while in the compression phase the bubbles implode to generate pressures of around 1000 bar at the equipment surface – a pressure so high that the material can be eroded (though the higher the frequency, the smaller the gas bubbles and the less aggressive the surface interaction).

Chemical fine-tuning

An alternative cleaning method is based on non-aqueous solvents that act on contamination by dilution. Right now, modified alcohols are the most commonly used solvents at CERN – a result of their low selectivity and minimal toxicity – with the cleaning operation performed in a sealed machine to minimise the environmental impacts of the volatile chemicals. While the range of organic products on which solvents are effective is usually wider than that of detergents, they cannot efficiently remove polar contaminants like salt stains. Another drawback is the risk of contaminants recollecting on the component surface when the liquid does not flow adequately.

Ultimately, the choice of detergent versus solvent relies on the experience of the operator and on guidelines linked to the type of vacuum component and the nature of the contamination. In general, the coating of components destined for ultrahigh-vacuum (UHV) applications will require a preliminary cleaning phase with detergents. Meanwhile, solvents are the optimum choice when there are no stringent cleanliness requirements – e.g. degreasing of filters for cryoplants or during the component assembly phase – and for surfaces that are prone to react with or retain water – e.g. steel laminations for magnets, ceramics and welded bellows. (It is worth noting that trapped water is released in vacuum, compromising the achievement of the required pressure, while wet surfaces are seeds for corrosion in air.)

After rinsing and drying, the components are then ready for installation in the accelerator or for ongoing surface modification. In the case of the latter, the chemical treatments aim to generate a thinner, more compact oxide layer and/or a smoother surface – essential for subsequent plating processes. As such, the components can undergo etching, pickling and passivation (to reduce the chemical reactivity of the surface). Consider the copper components for the LHC’s current-lead support: before brazing (a joining process using a melted filler metal), these components are pickled in hydrochloric acid and passivated in chromic acid. Similarly, the aluminium contacts of busbars (for local high-current power distribution) must be pickled by caustic soda and/or a mixture of nitric and hydrofluoric acid before silver coating. Another instructive example is found in the LHCb’s Vertex Locator (VELO) detector, in which the aluminium RF-box window is thinned down to 150 microns by caustic soda.

Safety always comes first in Building 107

Safety-critical thinking is hard-wired into the operational DNA of CERN’s Building 107, underpinning the day-to-day storage, handling and large-scale use of chemical products for surface treatments. That safety-first mantra means the 5000 m2 facility is able to confine all hazards inside its walls, such that risks for the surrounding neighbourhood and environment are negligible. Among the key features of Building 107:

• There are retention basins that allow containment of the liquid from all surface-treatment tanks (plus, even in the unlikely case of a fire, there is enough retention capacity for the water pumped by the firefighting teams).

• The retention basins have leak detection sensors, pumping systems, buffer tanks and a special coating that’s able to withstand more than 100 types of chemical for several days in the event of a leak.

• Toxic and corrosive vapours are extracted continuously from the tanks and washed in dedicated scrubbers, while any escaped solvents are adsorbed on active carbon filters.

• A continuous spray of alkaline solution transfers toxic products (liquid phase) for decontamination at CERN’s wastewater treatment plant.

• In terms of fire prevention, all plastics used for the treatment tanks and extraction ducts are made of self-extinguishing polypropylene – removing the source of energy to sustain the flames.

• The safety of technicians is ensured by strict operating procedures (including regulated building access), enhanced air extraction and the storage of incompatible products in separate retention zones.

• State-of-the-art sensors provide permanent monitoring of critical airborne products and link to local and fire-brigade alarms.

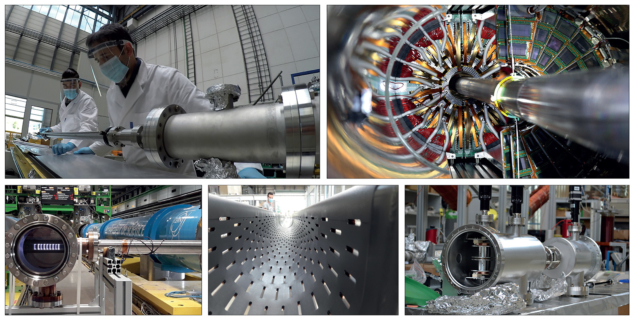

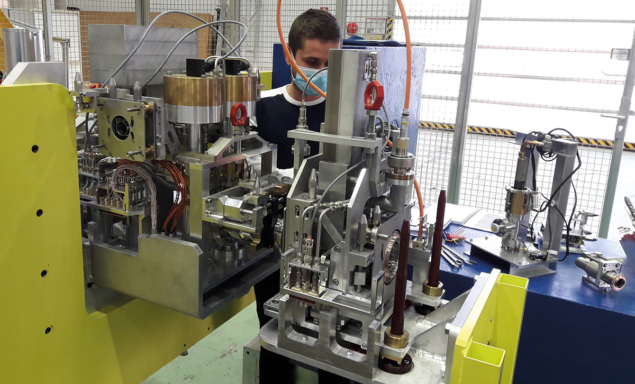

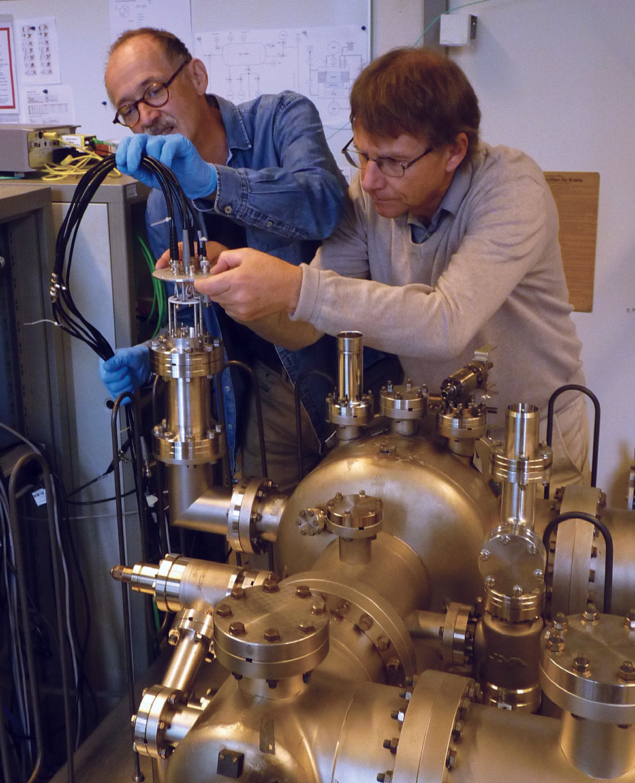

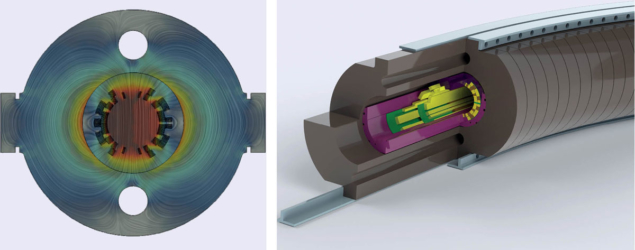

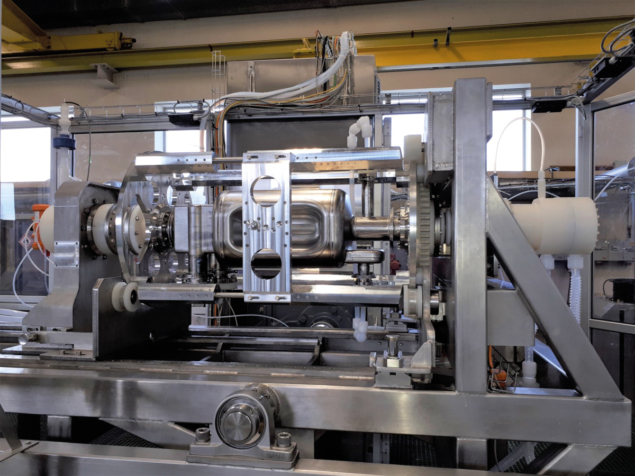

Frequently, chemical or electrochemical polishing are required in addition to cleaning. Polishing removes the damaged subsurface layer generated by lamination and machining – essentially a tangle of voids, excess dislocations and impurities. In this context, it is worth highlighting the surface treatments for RF acceleration cavities. Best practice dictates that materials for such applications – essentially niobium and copper – must undergo chemical and/or electrochemical polishing to remove a surface layer of 150 micron thickness. As such, the final state of the material’s topmost layer is flawless and without residual stress. (Note that while mechanical polishing can achieve lower roughness, it leaves behind underlayer defects and abrasive contaminations that are incompatible with the high-voltage operation of RF cavities.) A related example is the niobium RFD crab cavity for the HL-LHC project. This complex-shaped object is treated by a dedicated machine that can provide rotation while chemically polishing with a mixture of nitric, hydrofluoric and phosphoric acids. In this chemical triple-whammy, the first acid oxidises niobium; the second fluorinates and “solubilises” the oxide; and the last acts as a buffer controlling the reaction rate.

Another intriguing opportunity is the switch from wet to dry chemistry for certain niche applications

The final set of treatments involves plating the component with a functional material. In outline, this process works by immersing the accelerator component (negatively biased) into an electrolytic solution containing the functional metal ions. The electrolytic solution is strongly acid or basic to ensure high electrical conductivity, with deposition occurring via reduction of the metallic ions on the component surface – all of which occurs in dedicated tanks where the solution is heated, agitated and monitored throughout.

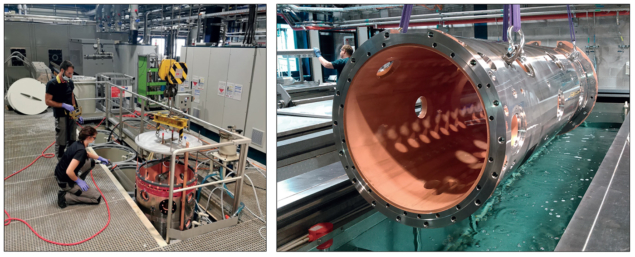

At CERN, we have extensive experience in the electroplating of large components and can plate with copper, silver, nickel, gold and rhodium. Copper is by far the most common option and its thickness is frequently of the order of hundreds of microns (while gold and rhodium are rarely thicker than a few microns). Current capacity varies from 7 m-long pipes (around 10 cm diameter) to 3.5 m-long tanks (up to 0.8 m diameter). It is worth noting that these capabilities are also used to support other big-science facilities – including a recent implementation for the Drift Tube Linac tanks of the European Spallation Source (ESS) in Lund, Sweden.

Chemical innovation

Notwithstanding the day-to-day provision of a range of surface treatments, the Building 107 chemistry team is also tasked with driving process innovation. As safety is our priority, the main focus is on the replacement of toxic products with eco- and personnel-friendly chemicals. A key challenge in this regard is to substitute chromic acid and cyanate baths, and ideally limit the current extensive use of hydrofluoric acid – a development track inextricably linked to the commercialisation of new products and close cooperation with our partners in industry.

Elsewhere, the chemistry team has registered impressive progress on several fronts. There’s the electroforming of tiny vacuum chambers for electron accelerators and RF cavities with seamless enclosure of flanges at the extremities. This R&D project is supported by CERN’s knowledge transfer funds and has already been proposed for the prototyping of the vacuum chamber of the Swiss Light Source II. A parallel line of enquiry includes production of self-supported graphite films for electron strippers that increase the positive charge of ions in beams – with the films fabricated either by etching the metallic support or by electrochemical delamination (a technique already proposed for the production of graphene foils).

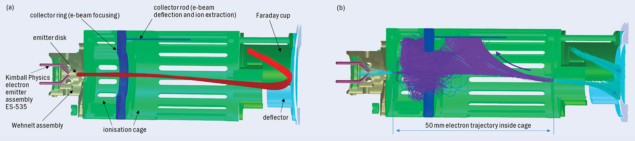

Another intriguing opportunity is the switch from wet to dry chemistry for certain niche applications. A case in point is the use of oxygen plasmas for surface cleaning – a technique hitherto largely confined to industry but with one notable exception in accelerator science. The beryllium central beam pipes of the four main LHC experiments, for example, were cleaned by oxygen plasma before non-evaporable-getter coating, removing carbon contamination without dislodging atoms of the hazardous metal. Following on from this successful use case, we are presently studying oxygen plasmas for in situ decontamination and cleaning of radioactive components, a priority task for the chemistry team as the HL-LHC era approaches.

The future of surface chemistry at CERN looks bright – and noticeably greener. The Building 107 team, for its part, remains focused on developing chemical surface treatments that are, first and foremost, safer and, in some cases, drier.