Sweden’s MAX IV synchrotron radiation facility is among an elite cadre of advanced X-ray sources, shedding light on the structure and behaviour of matter at the atomic and molecular level across a range of fundamental and applied disciplines – from clean-energy technologies to pharma and healthcare, from structural biology and nanotech to food science and cultural heritage.

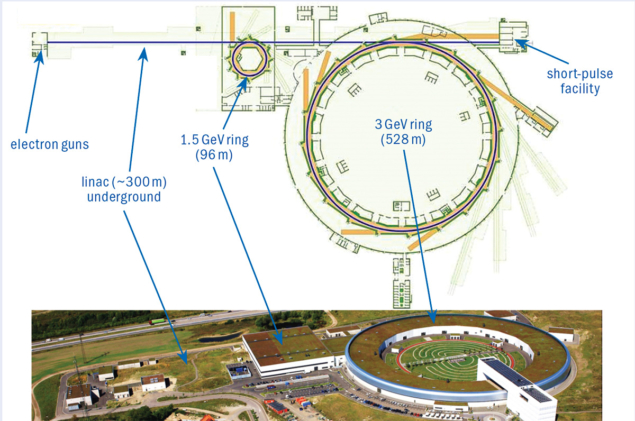

In terms of core building blocks, this fourth-generation light source – which was inaugurated in 2016 – consists of a linear electron accelerator plus 1.5 and 3 GeV electron storage rings (with the two rings optimised for the production of soft and hard X rays, respectively). As well as delivering beam to a short-pulse facility, the linac serves as a full-energy injector to the two storage rings which, in turn, provide photons that are extracted for user experiments across 14 specialist beamlines.

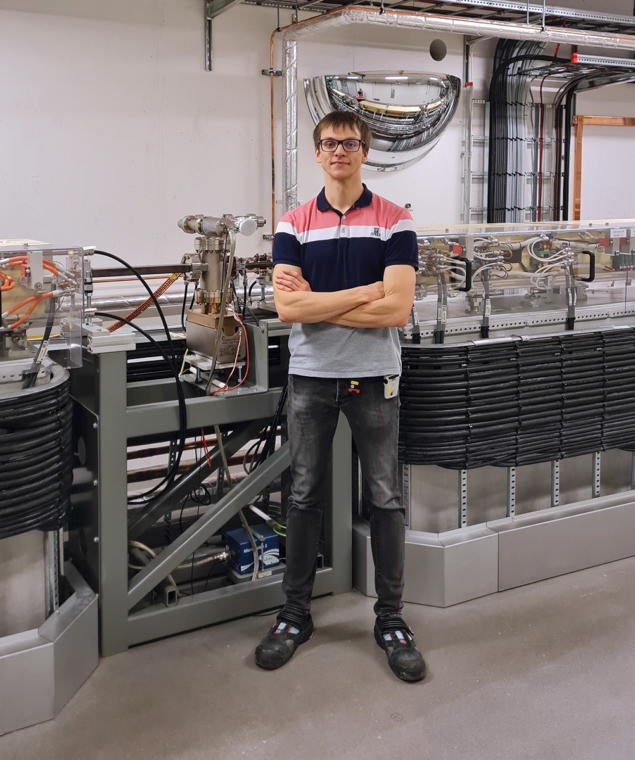

Underpinning all of this is a ground-breaking implementation of ultrahigh-vacuum (UHV) technologies within MAX IV’s 3 GeV electron storage ring – the first synchrotron storage ring in which the inner surface of almost all the vacuum chambers along its circumference are coated with non-evaporable-getter (NEG) thin film for distributed pumping and low dynamic outgassing. Here, Marek Grabski, MAX IV vacuum section leader, gives CERN Courier the insider take on a unique vacuum installation and its subsequent operational validation.

What are the main design challenges associated with the 3 GeV storage-ring vacuum system?

We were up against a number of technical constraints that necessitated an innovative approach to vacuum design. The vacuum chambers, for example, are encapsulated within the storage ring’s compact magnet blocks with bore apertures of 25 mm diameter (see “The MAX IV 3 GeV storage ring: unique technologies, unprecedented performance”). What’s more, there are requirements for long beam lifetime, space limitations imposed by the magnet design, the need for heat dissipation from incoming synchrotron radiation, as well as minimal beam-coupling impedance.

The answer, it turned out, is a baseline design concept that exploits NEG thin-film coatings, a technology originally pioneered by CERN that combines distributed pumping of active residual gas species with low photon-stimulated desorption. The NEG coating was applied by magnetron sputtering to almost all the inner surfaces (98% lengthwise) of the vacuum chambers along the electron beam path. As a consequence, there are only three lumped ion pumps fitted on each standard “achromat” (20 achromats in all, with a single acromat measuring 26.4 m end-to-end). That’s far fewer than typically seen in other advanced synchrotron light sources.

The MAX IV 3 GeV storage ring: unique technologies, unprecedented performance

Among the must-have user requirements for the 3 GeV storage ring was the specified design goal of reaching ultralow electron-beam emittance (and ultrahigh brightness) within a relatively small circumference (528 m). As such, the bare lattice natural emittance for the 3 GeV ring is 328 pm rad – more than an order of magnitude lower than typically achieved by previous third-generation storage rings in the same energy range.

Even though the fundamental concepts for realising ultralow emittance had been laid out in the early 1990s, many in the synchrotron community remained sceptical that the innovative technical solutions proposed for MAX IV would work. Despite the naysayers, on 25 August 2015 the first electron beam circulated in the 3 GeV storage ring and, over time, all design parameters were realised: the fourth generation of storage-ring-based light sources was born.

Stringent beam parameters

The MAX IV 3 GeV storage ring represents the first deployment of a so-called multibend achromat magnet lattice in an accelerator of this type, with the large number of bending magnets central to ensuring ultralow horizontal beam emittance. In all, there are seven bending magnets per achromat (and 20 achromats making up the complete storage ring).

Not surprisingly, miniaturisation is a priority in order to accommodate the 140 magnet blocks – each consisting of a dipole magnet and other magnet types (quadrupoles, sextupoles, octupoles and correctors) – into the ring circumference. This was achieved by CNC machining the bending magnets from a single piece of solid steel (with high tolerances) and combining them with other magnet types into a single integrated block. All magnets within one block are mechanically referenced, with only the block as a whole aligned on a concrete girder.

Vacuum innovation

Meanwhile, the vacuum system design for the 3 GeV storage ring also required plenty of innovative thinking, key to which was the close collaboration between MAX IV and the vacuum team at the ALBA Synchrotron in Barcelona. For starters, the storage-ring vacuum vessels are made from extruded, oxygen-free, silver-bearing copper tubes (22 mm inner diameter, 1 mm wall thickness).

Copper’s superior electrical and thermal conductivities are crucial when it comes to heat dissipation and electron beam impedance. The majority of the chamber walls act as heat absorbers, directly intercepting synchrotron radiation coming from the bending magnets. The resulting heat is dissipated by cooling water flowing in channels welded on the outer side of the vacuum chambers. Copper also absorbs unwanted radiation better than aluminium, offering enhanced protection for key hardware and instrumentation in the tunnel.

The use of crotch absorbers for extraction of the photon beam is limited to one unit per achromat, while the section where synchrotron radiation is extracted to the beamlines is the only place where the vacuum vessels incorporate an antechamber. Herein the system design is particularly challenging, with the need for additional cooling blocks to be introduced on the vacuum chambers with the highest heat loads.

Other important components of the vacuum system are the beam position monitors (BPMs), which are needed to keep the synchrotron beam on an optimised orbit. There are 10 BPMs in each of the 20 achromats, all of them decoupled thermally and mechanically from the vacuum chambers through RF-shielded bellows that also allow longitudinal expansion and small transversal movement of the chambers.

Ultimately, the space constraints imposed by the closed magnet block design – as well as the aggregate number of blocks along the ring circumference – was a big factor in the decision to implement a NEG-based pumping solution for MAX IV’s 3 GeV storage ring. It’s simply not possible to incorporate sufficient lumped ion pumps to keep the pressure inside the accelerator at the required level (below 1 × 10–9 mbar) to achieve the desired beam lifetime while minimising residual gas–beam interactions.

Operationally, it’s worth noting that a purified neon venting scheme (originally developed at CERN) has emerged as the best-practice solution for vacuum interventions and replacement or upgrade of vacuum chambers and components. As evidenced on two occasions so far (in 2018 and 2020), the benefits include significantly reduced downtime and risk management when splitting magnets and reactivating the NEG coating.

How important was collaboration with CERN’s vacuum group on the NEG coatings?

Put simply, the large-scale deployment of NEG coatings as the core vacuum technology for the 3 GeV storage ring would not have been possible without the collaboration and support of CERN’s vacuum, surfaces and coatings (VSC) group. Working together, our main objective was to ensure that all the substrates used for chamber manufacturing, as well as the compact geometry of the 3 GeV storage-ring vacuum vessels, were compatible with the NEG coating process (in terms of coating adhesion, thickness, composition and activation behaviour). Key to success was the deep domain knowledge and proactive technical support of the VSC group, as well as access to CERN’s specialist facilities, including the mechanical workshop, vacuum laboratory and surface treatment plant.

What did the manufacturing model look like for this vacuum system?

Because of the technology and knowledge transfer from CERN to industry, it was possible for the majority of the vacuum chambers to be manufactured, cleaned, NEG-coated and tested by a single commercial supplier – in this case, FMB Feinwerk- und Messtechnik in Berlin, Germany. Lengthwise, 70% of the chambers were NEG-coated by the same vendor. Naturally, the manufacturing of all chambers had to be compatible with the NEG coating, which meant careful selection and verification of materials, joining methods (brazing) and handling. Equally important, the raw materials needed to undergo surface treatment compatible with the coating, with the final surface cleaning certified by CERN to ensure good film adhesion under all operating conditions – a potential bottleneck that was navigated thanks to excellent collaboration between the three parties involved.

To spread the load, and to relieve the pressure on our commercial supplier ahead of system installation (which commenced in late 2014), it’s worth noting that most geometrically complicated chambers (including vacuum vessels with a 5 mm vertical aperture antechamber) were NEG-coated at CERN. Further NEG coating support was provided through a parallel collaboration with the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble.

How did you handle the installation phase?

This was a busy – and at times stressful – phase of the project, not least because all the vacuum chambers were being delivered “just-in-time” for final assembly in situ. This approach was possible thanks to exhaustive testing and qualification of all vacuum components prior to shipping from the commercial vendor, while extensive dialogue with the MAX IV team helped to resolve any issues arising before the vacuum components left the factory.

Owing to the tight schedule for installation – just eight months – we initiated a collaboration with the Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics (BINP) in Russia to provide additional support. For the duration of the installation phase, we had two teams of specialists from BINP working alongside (and coordinated by) the MAX IV vacuum team. All vacuum-related processes – including assembly, testing, baking and NEG activation of each achromat (at 180 °C) – took place inside the accelerator tunnel directly above the opened lower magnet blocks of MAX IV’s multibend achromat (MBA) lattice. Our installation approach, though unconventional, yielded many advantages – not least, a reduction in the risks related to transportation of assembled vacuum sectors as well as reduced alignment issues.

Presumably not everything went to plan through installation and acceptance?

One of the issues we encountered during the initial installation phase was a localised peeling of the NEG coating on the RF-shielded bellows assembly of several vacuum vessels. This was addressed as a matter of priority – NEG film fragments falling into the beam path is a show-stopper – and all the effected modules were replaced by the vendor in double-quick time. More broadly, the experience of the BINP staff meant difficulties with the geometry of a few chambers could also be resolved on the spot, while the just-in-time delivery of all the main vacuum components worked well, such that the installation was completed successfully and on time. After completion of several achromats, we installed straight sections in between while the RF cavities were integrated and conditioned in situ.

How has the vacuum system performed from the commissioning phase and into regular operation?

Bear in mind that MAX IV was the first synchrotron light source to apply NEG technology on such a scale. We were breaking new ground at the time, so there were credible concerns regarding the conditioning and long-term reliability of the NEG vacuum system – and, of course, possible effects on machine operation and performance. From commissioning into regular operations, however, it’s clear that the NEG pumping system is reliable, robust and efficient in delivering low dynamic pressure in the UHV regime.

Initial concerns around potential saturation of the NEG coating in the early stages of commissioning (when pressures are high) proved to be unfounded, while the same is true for the risk associated with peeling of the coating (and potential impacts on beam lifetime). We did address a few issues with hot-spots on the vacuum chambers during system conditioning, though again the overall impacts on machine performance were minimal.

To sum up: the design current of 500 mA was successfully injected and stored in November 2018, proving that the vacuum system can handle the intense synchrotron radiation. After more than six years of operation, and 5000 Ah of accumulated beam dose, it is clear the vacuum system is reliable and provides sustained UHV conditions for the circulating beam – a performance, moreover, that matches or even exceeds that of conventional vacuum systems used in other storage rings.

What are the main lessons your team learned along the way through design, installation, commissioning and operation of the 3 GeV storage-ring vacuum system?

The unique parameters of the 3 GeV storage ring were delivered according to specification and per our anticipated timeline at the end of 2015. Successful project delivery was only possible by building on the collective experience and know-how of staff at MAX-lab (MAX IV’s predecessor) constructing and operating accelerators since the 1970s – and especially the lab’s “explorer mindset” for the early-adoption of new ideas and enabling technologies. Equally important, the commitment and team spirit of our technical staff, reinforced by our collaborations with colleagues at ALBA, CERN, ESRF and BINP, were fundamental to the realisation of a relatively simple, efficient and compact vacuum solution.

Operationally, it’s worth adding that there are many dependencies between the chosen enabling technologies in a project as complex as the MAX IV 3 GeV storage ring. As such, it was essential for us to take a holistic view of the vacuum system from the start, with the choice of a NEG pumping solution enforcing constraints across many aspects of the design – for example, chamber geometry, substrate type, surface treatment and the need for bellows. The earlier such knowledge is gathered within the laboratory, the more it pays off during construction and operation. Suffice to say, the design and technology solutions employed by MAX IV have opened the door for other advanced light sources to navigate and build on our experience.

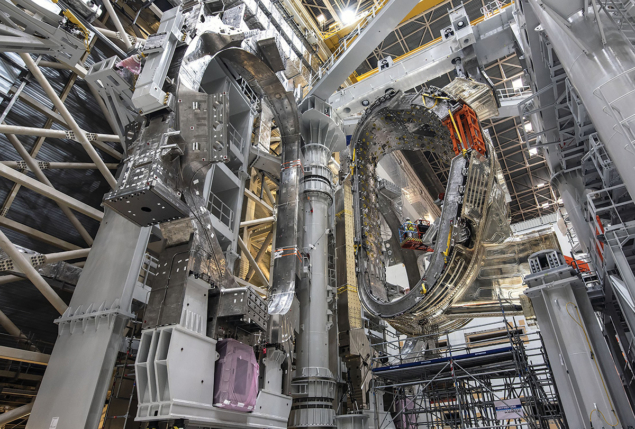

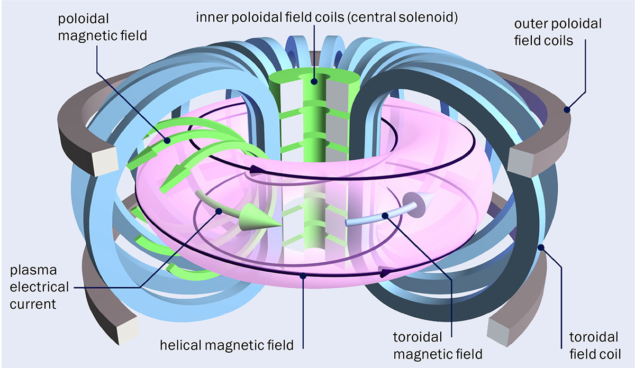

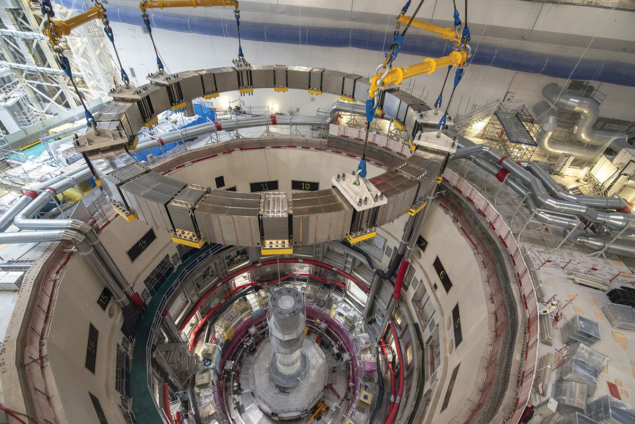

ITER has now reached the stage where about half of the large magnet components have arrived on site and many more are nearing completion at manufacturing locations distributed throughout the ITER partners. Although we still have several years of challenging on-site assembly ahead, the acceptance tests and first-of-a-kind assembly are teaching us a lot about the magnet quality and possible improvements for future tokamaks.

ITER has now reached the stage where about half of the large magnet components have arrived on site and many more are nearing completion at manufacturing locations distributed throughout the ITER partners. Although we still have several years of challenging on-site assembly ahead, the acceptance tests and first-of-a-kind assembly are teaching us a lot about the magnet quality and possible improvements for future tokamaks. After completing his PhD at Cambridge University on the fluid mechanics of turbomachinery, Neil Mitchell entered the nuclear fusion world in 1981 during the completion of the JET tokamak, and participated extensively in the early superconducting strand and conductor development programme of the EU in the 1980s, as well as in the design/manufacturing of several small copper-magnet-based magnetic fusion devices, including COMPASS at UKAEA. He was involved in the prototype manufacturing and testing of the superconductors that eventually became the main building blocks of the ITER magnets, and participated in the development and first tests of facilities such as Fenix at LLNL and Sultan at PSI. He has filled several positions within the ITER project after joining as one of the founder members in 1988, in particular, as the section leader for the ITER conductor in the 1990s with the highly successful construction and test of the CSMC in Japan and TFMC in Europe, and then after as division head responsible for the magnet procurement. He was responsible for finalising the magnet design, negotiating the magnet in-kind procurement agreements with the ITER Home Institutes and direct contracts, following and assisting the industrial production qualification and ramp up in multiple suppliers in EU, Japan, Korea, China, US and Russia. The ITER conductor production was completed in 2016 and now with the completion of the first-of-kind magnets, the delivery to the site of several coils and the placement of the first PF coil in the cryostat, he is working as an advisor to the ITER director. He is deeply involved in problem solving in the interfaces to the ITER on-site construction as the ITER magnets are delivered, contributing to the magnet control and commissioning plans, and advising the EU on the design of a next-generation fusion reactor.

After completing his PhD at Cambridge University on the fluid mechanics of turbomachinery, Neil Mitchell entered the nuclear fusion world in 1981 during the completion of the JET tokamak, and participated extensively in the early superconducting strand and conductor development programme of the EU in the 1980s, as well as in the design/manufacturing of several small copper-magnet-based magnetic fusion devices, including COMPASS at UKAEA. He was involved in the prototype manufacturing and testing of the superconductors that eventually became the main building blocks of the ITER magnets, and participated in the development and first tests of facilities such as Fenix at LLNL and Sultan at PSI. He has filled several positions within the ITER project after joining as one of the founder members in 1988, in particular, as the section leader for the ITER conductor in the 1990s with the highly successful construction and test of the CSMC in Japan and TFMC in Europe, and then after as division head responsible for the magnet procurement. He was responsible for finalising the magnet design, negotiating the magnet in-kind procurement agreements with the ITER Home Institutes and direct contracts, following and assisting the industrial production qualification and ramp up in multiple suppliers in EU, Japan, Korea, China, US and Russia. The ITER conductor production was completed in 2016 and now with the completion of the first-of-kind magnets, the delivery to the site of several coils and the placement of the first PF coil in the cryostat, he is working as an advisor to the ITER director. He is deeply involved in problem solving in the interfaces to the ITER on-site construction as the ITER magnets are delivered, contributing to the magnet control and commissioning plans, and advising the EU on the design of a next-generation fusion reactor.