In the world of communication, everyone has a role to play. During the past two decades, the ability of researchers to communicate their work to funding agencies, policymakers, entrepreneurs and the public at large has become an increasingly important part of their job. Scientists play a fundamental role in society, generally enjoying an authoritative status, and this makes us accountable.

Science communication is not just a way to share knowledge, it is also about educating new generations in the scientific approach and attracting young people to scientific careers. In addition, fundamental research drives the development of technology and innovation, playing an important role in providing solutions in challenging areas such as health care, the provision of food and safety. This obliges researchers to disseminate the results of their work.

Evolving attitudes

Although science communication is becoming increasingly unavoidable, the skills it requires are not yet universal and some scientists are not prepared to do it. Of course there are risks involved. Communication can distract individuals from research and objectives, or, if done badly, can undermine the very messages that the scientist needs to convey. The European Researchers’ Night is a highly successful annual event that was initiated in 2005 as a European Commission Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action, and offers an opportunity for scientists to get more involved in science communication. It falls every final Friday of September, and illustrates how quickly attitudes are evolving.

In 2006, with a small group of researchers from the Italian National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN) located close to Frascati, we took part in one of the first Researchers’ Night events. Frascati is surrounded by important scientific institutions and universities, and from the start the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development, the European Space Agency and the National Institute for Astrophysics joined the collaboration with INFN, along with the Municipality of Frascati and the Cultural and Research Department of the Lazio region, which co-funded the initiative.

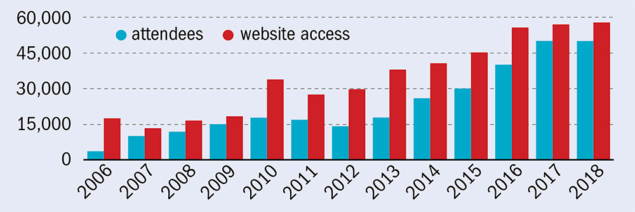

Since then, thousands of researchers, citizens, public and private institutions have worked together to change the public perception of science and of the infrastructure in the Frascati and Lazio regions, supported by the programme. Today, after 13 editions, it involves more than 60 scientific partners spread from the north to the south of Italy in 30 cities, and attracts more than 50,000 attendees, with significant media impact (figure 1). Moreover, it has now evolved to become a week-long event, is linked to many related events throughout the year, and has triggered many institutions to develop their own science-communication projects.

Analysing the successive Frascati Researchers’ Night projects allows a better understanding of the evolution of science-communication methodology. Back in 2006, scientists started to open their laboratories and research infrastructures to present their jobs in the most comprehensible way, with a view to increasing the scientific literacy of the public and to fill their “deficit” of knowledge. They then tried to create a direct dialogue by meeting people in public spaces such as squares and bars, discussing the more practical aspects of science, such as how public money is spent, and how much researchers are responsible for their work. Those were the years in which the socio-economic crisis started to unfold. It was also the beginning of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 programme, when economic growth and terms such as “innovation” started to substitute scientific progress and discovery. It was therefore becoming more important than ever to engage with the public and keep the science flag flying.

In recent years, this approach has changed. Two biannual projects that are also part of a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Action – Made in Science and BEES (BE a citizEn Scientist) underline a different vision of science and of the methodology of communication. Made in Science (which was live between 2016 and 2017) was supposed to represent the “trademark” of research, aiming to communicate to society the importance of the science production chain in terms of quality, identity, creativity, know-how and responsibility. In this chain, which starts from fundamental research and ends with social benefits, no one is excluded and must take part in the decision process and, where possible, in the research itself. Its successor, BEES (2018–2019), on the other hand, aims to bring citizens up close to the discovery process, showing how long it takes and how it can be tough and frustrating. Both projects follow the most recent trends in science communication based on a participative or “public engagement” model, rather than the traditional “deficit” model. Here, researchers are not the main actors but facilitators of the learning process with a specific role: the expert one.

Nerd or not a nerd?

Nevertheless, this evolution of science communication isn’t all positive. There are many examples of problems in science communication: the explosion of concerns about science (vaccines, autism, GMO, homeopathy, etc); the avoidance of science and technology in preference to returning to a more “natural” life; the exploitation of science results (positive or negative) to support conspiracy theories or influence democracies; and overplaying the benefits for knowledge and technology transfer, to list a few examples. Last but not least, some strong bias still remains among both scientists and audiences, limiting the effectiveness of communication.

The first, and probably the hardest, is the stereotype bias: are you a “nerd”, or do you feel like a nerd? Often scientists refer to themselves as a category that can’t be understood by society, consequently limiting their capacity to interact with the public. On the other hand, scientists are sometimes real nerds, and seen by the public as nerds. This is true for all job categories, but in the case of scientists this strongly conditions their ability to communicate.

Age, gender and technological bias also still play a fundamental role, especially in the most developed European countries. Young people may understand science and technology more easily, while women still do not seem to have full access to scientific careers and to the exploitation of technology. Although the transition from a deficit to a participative model is already common in education and democratic societies, it is not yet completed in science, which is likely because of the strong bias that still seems to exist among researchers and audiences. The Marie Skłodowska-Curie European Researchers’ Night is a powerful way in which scientists can address such issues.