What do collider phenomenologists do?

I tend to prefer the term particle phenomenology because the collider is just the tool that we use. However, compared to other experiments, such as those searching for dark matter or axions, colliders provide a controlled laboratory where you decide how many collisions and what energy these collisions should have. This is quite unique. Today, accelerators and detectors have reached an immense level of sophistication, and this allows us to perform a vast amount of fundamental measurements. So, the field spans precision measurements of fundamental properties of particles, in particular of the Higgs boson, consistency tests of the Standard Model (SM), direct and indirect searches for new physics, measurements of rare decays, and much more. For essentially all these topics we have had new results in recent years, so it’s a very active and continuously evolving field. But of course we do not just measure things for the sake of it. We have big, fundamental questions and we are looking for hints from LHC data as to how to address them.

What’s hot in the field today?

One topic that I think is very cool is that we can benefit from the LHC, in its current setup, also as lepton collider. In fact, at the LHC we are looking at elementary collisions between the proton’s constituents, quarks and gluons. But since the proton is charged, it also emits photons, and one can talk about the photon parton-distribution function (PDF), i.e. the photonic content of protons. These photons can split into lepton pairs, so when one collides protons one is also colliding leptons. The fascinating thing is that the “content” of leptons in protons is rather democratic, so one can look at collisions between, say, a muon and a tau lepton – something that can’t be done even at future proposed lepton colliders. Furthermore, by picking up a lepton from one proton and a quark from the other proton, one can place new constraints on leptoquarks, and plenty of other things. This idea was already proposed in the 1990s, but was essentially forgotten because the lepton PDF was not known. Now we know this very precisely, bringing new possibilities. But let me stress that this is just one idea – there are many other new ideas out there. For instance, one major branch of phenomenology is to use machine learning or deep learning to recognise the SM and extract from data what is not SM-like.

I’m the first female director, which of course is a great responsibility

How does the Max Planck Institute differ from your previous positions, for example at CERN and Oxford?

A long time ago, somebody told me that the best thing that can happen to you in Germany is the Max Planck Society. It’s true. You are given independence and the means to fully focus on research and ideas, largely free of teaching duties or the need to apply for grants. Also, there are very valuable interactions with universities, be it in research or via the International Max Planck Research Schools for PhD students. Our institute in Munich is a very unique place. One can feel it immediately. As a guest in the theory department, for example, you get to sit in the Heisenberg office, which feels like going back in time. Our institute was founded in Berlin in 1917 with Albert Einstein as a first director. In 1958 the institute moved to Munich with Werner Heisenberg as director. After more than 100 years I’m the first female director, which of course is a great responsibility. But I also really loved both CERN and Oxford. At CERN I felt like I was at the centre of the world. It is such a vibrant environment, and I loved the proximity to the experiments and the chats in the cafeteria about calculations or measurements. In Oxford I loved the multidisciplinary aspect, the dinners in college sitting next to other academics working in completely different fields. I guess I’m lucky that I’ve been in so many and such different places.

What is the biggest challenge to reach higher precision in quantum-field-theory calculations of key SM processes?

The biggest challenge is that often there is no single biggest challenge. For instance, for inclusive Higgs-boson production we have a number of theoretical uncertainties, but they are all quite comparable in size. This means that to reduce the overall uncertainty considerably, one needs to reduce all uncertainties, and they all have very different physics origins and difficulties – from a better understanding of the incoming parton densities and a better knowledge of the strong coupling constant, to higher order QCD or electroweak effects and effects related to heavy particles in virtual loops, etc. Computing power can be a liming factor for certain calculations, so making things numerically more efficient is also important. One of the main goals of the coming year will be the calculation of two to three scattering processes at the LHC at next-to-next-to-leading order (NNLO) in QCD. For instance, a milestone will be the calculation of top-pair production in association with a Higgs boson at that level of accuracy. This is the process where we can measure most directly the top-Yukawa coupling. The importance of this measurement can’t be overstressed. While the big discovery at the LHC is so far the Higgs boson, one should also remember that the Yukawa interaction is a new type of fundamental interaction, which is proportional to the mass of the particle, just like gravity, but yet so different from gravity. For some calculations, NNLO is already enough in terms of perturbative precision; going to N3LO doesn’t really add much yet. But there are a few cases where it helps already, such as super-clean Drell–Yan processes.

Is there a level of precision of LHC measurements beyond which indirect searches for new physics are no longer fruitful?

We will never rule out precision measurements as a route to search for new physics. We can always extend the reach and enhance the sensitivity of indirect searches. By increasing precision, we are exploring deeper in the ultraviolet region, where we can start to become sensitive to states exchanged in the loops that are more and more heavy. There is a limit, but we are very far from it. It’s like looking with a better and better microscope: the better the resolution, the more one can explore. However, the experimental precision has to go hand in hand with theoretical precision, and this is where the real challenge for phenomenologists lies. Of course, if you have a super precise measurement but no theory prediction, or vice versa, then you can’t do much with it. With the Higgs boson I am confident that the theory calculations will not be the deal breaker. We will eventually hit the wall in terms of experimental precision, but you can’t put a figure on where this will happen. Until you see a deviation you are never really done.

How would you characterise the state of particle physics today?

When I entered the field as a student, there were high expectations that supersymmetry would be discovered quickly at the LHC. Now things have turned out to be different, but this is what makes it exciting and challenging – even more so, because the same mysteries are still there. We have big, fundamental questions. We have hints from theory, from experiments. We have a powerful, multi-purpose machine – the LHC – that is only just getting started and will provide much more data. Of course, expectations like the quick discovery of supersymmetry have not been fulfilled, but nature is how it is. I think that progress in physics is driven by experiments. We have beautiful exceptions where progress comes from theory, like general relativity, or the postulation of the mechanism for electroweak symmetry breaking. When I think about the Higgs mechanism, I am still astonished that such a simple and powerful idea postulated in 1964 turns out to be realised in nature. But these cases, where theory precedes experiments, are the exception not the rule. In most cases progress in physics comes from observations. After all, it is a natural science, it is not mathematics.

There are some questions that are really tough, and we may never really see an answer to. But with the LHC there are many other smaller questions we certainly can address, such as understanding the proton structure or studying the interaction potential between nucleons and strange baryons, which are relevant to understand the physics of neutron stars, and these are still advancing knowledge. The brightest minds are attracted to the biggest problems, and this will always draw young researchers into the field.

Is naturalness a good guiding force in fundamental research?

Yes. We have plenty of examples where naturalness, in the sense of a quadratic sensitivity to an unknown ultraviolet scale, leads to postulating a new particle: the energy of the electron field (leading to the positron), the charged and neutral pion mass difference (leading to the rho-meson) or the kaon transition rates and mixing, which led to the postulation of the existence of the charm quark in 1970, before its direct discovery in 1974 at SLAC and Brookhaven. In everyday life we constantly assume naturalness, so yes, it is puzzling that the Higgs mass appears to be fine-tuned. Certainly, there is a lot we still don’t understand here, but I would not give up on naturalness, at least not that easily. In the case of the electroweak naturalness problem, it is clear that any solution, such as supersymmetry or compositeness, will also leave an imprint in the Higgs couplings. So the LHC can, in principle, tell us about naturalness even if we do not discover new physics directly; we just have to measure very precisely if the Higgs boson couplings align on a straight line in the mass-versus-coupling plane.

The presence of dark matter is overwhelming in the universe and it is embarrassing that we know little to nothing about its nature

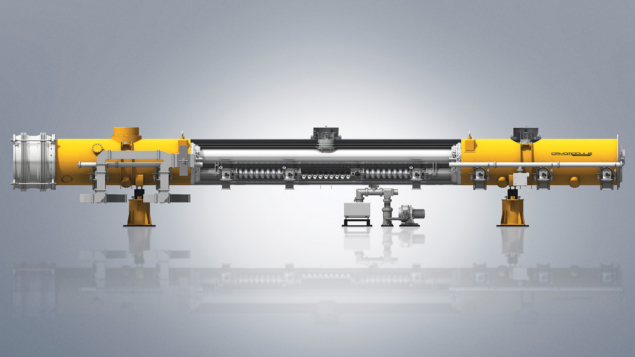

Which collider should follow the LHC?

That is the billion-dollar question – I mean, the 25 billion-dollar question! To me one should go for the machines that explore as much as possible the new energy frontier, namely a 100 TeV hadron collider. It is a compromise between what we might be able to achieve from a machine-building/accelerator/engineering point of view and really exploring a new frontier. For instance, at a 100 TeV machine one can measure the Higgs self-coupling, which is intimately connected with the Higgs potential and to the profound question of the stability of the vacuum.

Which open question would you most like to see answered during your career?

Probably the nature of dark matter. The presence of dark matter is overwhelming in the universe and it is embarrassing that we know little to nothing about its nature and properties. There are many exciting possibilities, ranging from the lightest neutral states in new-physics models to a non-particle-like interpretation, like black holes. Either way, an answer to this question would be an incredible breakthrough.