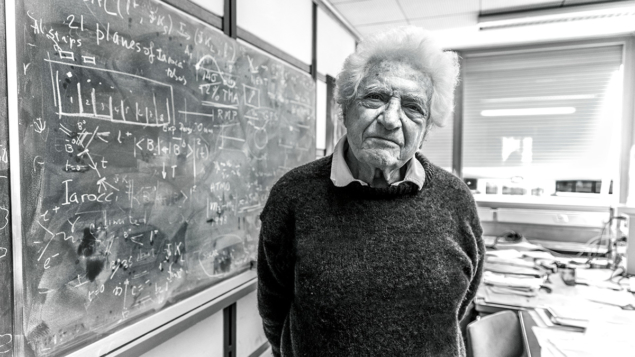

How did winning a Special Breakthrough Prize last year compare with the Nobel Prize?

It came as quite a surprise because as far as I know, none of the people who have been honoured with the Breakthrough Prize had already received the Nobel Prize. Of course nothing compares with the Nobel Prize in prestige, if only because of the long history of great scientists to whom it has been awarded in the past. But the Breakthrough Prize has its own special value to me because of the calibre of the young – well, I think of them as young – theoretical physicists who are really dominating the field and who make up the selection committee.

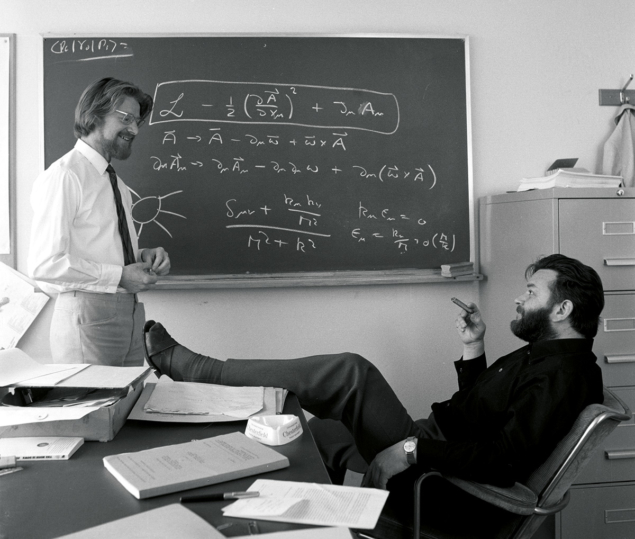

The prize committee stated that you would be a recognised leader in the field even if you hadn’t made your seminal 1967 contribution to the genesis of the Standard Model. What do you view as Weinberg’s greatest hits?

There’s no way I can answer that and maintain modesty! That work on the electroweak theory leading to the mass of the W and Z, and the existence and properties of the Higgs, was certainly the biggest splash. But it was rather untypical of me. My style is usually not to propose specific models that will lead to specific experimental predictions, but rather to interpret in a broad way what is going on and make very general remarks, like with the development of the point of view associated with effective field theory. Doing this I hope to try and change the way my fellow physicists look at things, without usually proposing anything specific. I have occasionally made predictions, some which actually worked, like calculating the pion–nucleon and pion–pion scattering lengths in the mid-1960s using the broken symmetry that had been proposed by Nambu. There were other things, like raising the whole issue of the cosmological constant before the discovery of the accelerated expansion of the universe. I worried about that – I gave a series of lectures at Harvard in which I finally concluded that the only way I can understand why there isn’t an enormous vacuum energy is because of some kind of anthropic selection. Together with two guys here at Austin, Paul Shapiro and Hugo Martel, we worked out what was the most likely value that would be found in terms of order of magnitude, which was later found to be correct. So I was very pleased that the Breakthrough Prize acknowledged some of those things that didn’t lead to specific predictions but changed a general framework.

I wish I could claim that I had predicted the neutrino mass

You coined the term effective field theory (EFT) and recently inaugurated the online lecture series All Things EFT. What is the importance of EFT today?

My thinking about EFTs has always been in part conditioned by thinking about how we can deal with a quantum theory of gravitation. You can’t represent gravity by a simple renormalisable theory like the Standard Model, so what do you do? In fact, you treat general relativity the same way you treat low-energy pions, which are described by a low-energy non-renormalisable theory. (You could say it’s a low-energy limit of QCD but its ingredients are totally different – instead of quarks and gluons you have pions). I showed how you can generate a power series for any given scattering amplitude in powers of energy rather than some small coupling constant. The whole idea of EFT is that any possible interaction is there: if it’s not forbidden it’s compulsory. But the higher, more complicated terms are suppressed by negative powers of some very large mass because the dimensionality of the coupling constants is such that they have negative powers of mass, like the gravitational constant. That’s why they’re so weak.

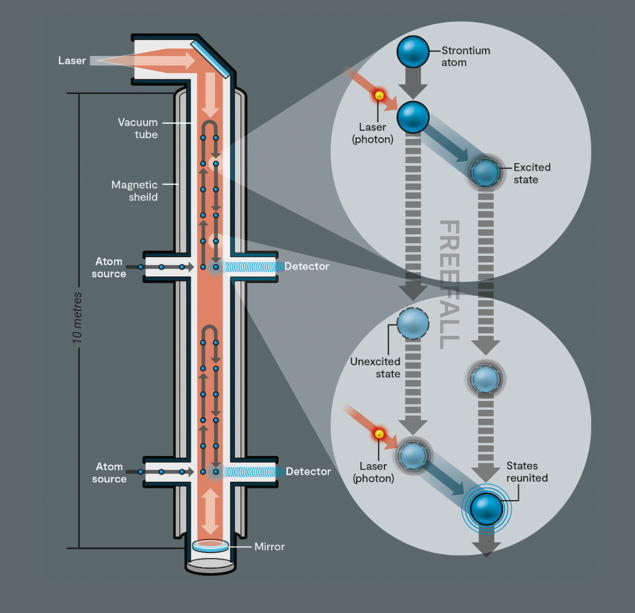

If you recognise that the Standard Model is probably a low-energy limit of some more general theory, then you can consider terms that make the theory non-renormalisable and generate corrections to it. In particular, the Standard Model has this beautiful feature that in its simplest renormalisable version there are symmetries that are automatic: at least to all orders of perturbation theory, it can’t violate the conservation of baryon or lepton number. But if the Standard Model just generates the first term in a power series in energy and you allow for more complicated non-renormalisable terms in the Lagrangian, then you find it’s very natural that there would be baryon and lepton non-conservation. In fact, the leading term of this sort is a term that violates lepton number and gives neutrinos the masses we observe. I wish I could claim that I had predicted the neutrino mass, but there already was evidence from the solar neutrino deficit and also it’s not certain that this is the explanation of neutrino masses. We could have Dirac neutrinos in which you have left and right neutrinos and antineutrinos coupling to the Higgs, and in that way get masses without any violation of lepton-number conservation. But I find that thoroughly repulsive because there’s no reason in that case why the neutrino masses should be so small, whereas in the EFT case we have Majorana neutrinos whose small masses are much more natural.

On this point, doesn’t the small value of the cosmological constant and Higgs mass undermine the EFT view by pointing to extreme fine-tuning?

Yes, they are a warning about things we don’t understand. The Higgs mass less so, after all it’s only about a hundred times larger than the proton mass and we know why the proton mass is so small compared to the GUT or Planck scale; it is because the proton gets it mass not from the quark masses, which have to do with the Higgs, but from the QCD forces, and we know that those become strong very slowly as you come down from high energy. We don’t understand this for the Higgs mass, which, after all, is a term in the Lagrangian, not like the proton mass. But it may be similar – that’s the old technicolour idea, that there is another coupling alongside QCD that becomes strong at some energy where it leads to a potential for the Higgs field, which then breaks electroweak symmetry. Now, I don’t have such a theory, and if I did I wouldn’t know how to test it. But there’s at least a hope for that. Whereas regards to the cosmological constant, I can’t think of anything along that line that would explain it. I think it was Nima Arkani-Hamed who said to me, “If the anthropic effect works for the cosmological constant, maybe that’s the answer with the Higgs mass – maybe it’s got to be small for anthropic reasons.” That’s very disturbing if it’s true, as we’re going to be left waving our hands. But I don’t know.

Maybe we have 2500 years ahead of us before we get to the next big step

Early last year you posted a preprint “Models of lepton and quark masses” in which you returned to the problem of the fermion mass hierarchy. How was it received?

Even in the abstract I advertise how this isn’t a realistic theory. It’s a problem that I first worked on almost 50 years ago. Just looking at the table of elementary particle masses I thought that the electron and the muon were crying out for an explanation. The electron mass looks like a radiative correction to the muon mass, so I spent the summer of 1972 on the back deck of our house in Cambridge, where I said, “This summer I am going to solve the problem of calculating the electron mass as an order-alpha correction to the muon mass.” I was able to prove that if in a theory it was natural in the technical sense that the electron would be massless in the tree approximation as a result of an accidental symmetry, then at higher order the mass would be finite. I wrote a paper, but then I just gave it up after no progress, until now when I went back to it, no longer young, and again I found models in which you do have an accidental symmetry. Now the idea is not just the muon and the electron, but the third generation feeding down to give masses to the second, which would then feed down to give masses to the first. Others have proposed what might be a more promising idea, that the only mass that isn’t zero in the tree approximation is the top mass, which is so much bigger than the others, and everything else feeds down from that. I just wanted to show the kinds of cancellations in infinites that can occur, and I worked out the calculations. I was hoping that when this paper came out some bright young physicist would come up with more realistic models, and use these calculational techniques – that hasn’t happened so far but it’s still pretty early.

What other inroads are there to the mass/flavour hierarchy problem?

The hope would be that experimentalists discover some correction to the Standard Model. The problem is that we don’t have a theory that goes beyond the Standard Model, so what we’re doing is floundering around looking for corrections in the model. So far, the only one discovered was the neutrino mass and that’s a very valuable piece of data which we so far have not figured out how to interpret. It definitely goes beyond the Standard Model – as I mentioned, I think it is a dimension-five operator in the effective field theory of which the Standard Model is the renormalisable part.

The big question is whether we can cut off some sub-problem that we can actually solve with what we already know. That’s what I was trying to do in my recent paper and did not succeed in getting anywhere realistically. If that is not possible, it may be that we can’t make progress without a much deeper theory where the constituents are much more massive, something like string theory or an asymptotically safe theory. I still think string theory is our best hope for the future, but this future seems to be much further away than we had hoped it would be. Then I keep being reminded of Democritus, who proposed the existence of atoms in around 400 BCE. Even as late as 1900 physicists like Mach doubted the existence of atoms. They didn’t become really nailed down until the first years of the 20th century. So maybe we have 2500 years ahead of us before we get to the next big step.

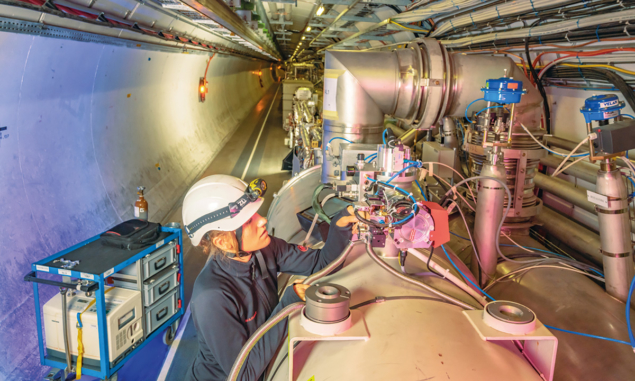

Recently the LHC produced the first evidence that the Higgs boson couples to a second-generation fermion, the muon. Is there reason to think the Higgs might not couple to all three generations?

Before the Higgs was discovered it seemed quite possible that the explanation of the hierarchy problem was that there was some new technicolour force that gradually became strong as you came from very high energy to lower energy, and that somewhere in the multi-TeV range it became strong enough to produce a breakdown of the electroweak symmetry. This was pushed by Lenny Susskind and myself, independently. The problem with that theory was then: how did the quarks and leptons get their masses? Because while it gave a very natural and attractive picture of how the W and Z get their masses, it left it really mysterious for the quarks and leptons. It’s still possible that something like technicolour is true. Then the Higgs coupling to the quarks and leptons gives them masses just as expected. But in the old days, when we took technicolour seriously as the mechanism for breaking electroweak symmetry, which, since the discovery of the Higgs we don’t take seriously anymore, even then there was the question of how, without a scalar field, can you give masses to the quarks and leptons. So, I would say today, it would be amazing if the quarks and leptons were not getting their masses from the expectation value of the Higgs field. It’s important now to see a very high precision test of all this, however, because small effects coming from new physics might show up as corrections. But these days any suggestion for future physics facilities gets involved in international politics, which I don’t include in my area of expertise.

It’s still possible that something like technicolour is true

Any more papers or books in the pipeline?

I have a book that’s in press at Cambridge University Press called Foundations of Modern Physics. It’s intended to be an advanced undergraduate textbook that takes you from the earliest work on atoms, through thermodynamics, transport theory, Brownian motion, to early quantum theory; then relativity and quantum mechanics, and I even have two chapters that probably go beyond what any undergraduate would want, on nuclear physics and quantum field theory. It unfortunately doesn’t fit into what would normally be the plan for an undergraduate course, so I don’t know if it will be widely

adopted as a textbook. It was the result of a lecture course I was asked to give called “thermodynamics and quantum physics” that has been taught at Austin for years. So, I said “alright”, and it gave me a chance to learn some thermodynamics and transport theory.