Enrico Fermi was born on 29 September 1901 in Rome to a family with no scientific traditions. His passion for natural sciences, and in particular for physics, was stimulated and guided in his school years by an engineer and family friend, Adolph Amidei, who recognized Fermi’s exceptional intellectual abilities and suggested admission to Pisa’s Scuola Normale Superiore.

After finishing high-school studies in Rome, in 1918 Fermi progressed to the prestigious Pisa Institute, after producing for the admission exam an essay on the characteristics of the propagation of sound, the authenticity of which the commissioners initially refused to believe.

Studies at Pisa did not pose any particular difficulties for the young Fermi, despite his having to be largely self-taught using material in foreign languages because nothing existed at the time in Italian on the new physics emerging around relativity and quantum theory. In those years in Italy, these new theories were absent from university teaching, and only mathematicians like Tullio Levi-Civita had the knowledge and insight to see their implications.

Working alone, between 1919 and 1922, Fermi built up a solid competence in relativity, statistical mechanics and the applications of quantum theory to such a degree that by 1920 the institute director, Luigi Puccianti, invited him to establish a series of seminars on quantum physics.

First published work

Even before taking any formal examinations, Fermi published his first important scientific work – a contribution to the theory of general relativity in which he introduced a particular system of coordinates that went on to become standard as Fermi coordinates – the beginning of a long series of scientific contributions and concepts associated with his name.

At Pisa, Fermi strengthened a friendship with Franco Rasetti and maintained scientific contact with his former high-school companion, Enrico Persico. In parallel with his outstanding ability in theoretical physics, Fermi developed a genuine feeling for experimental investigation, acquiring with Rasetti in the institute’s laboratory, which was put at their disposition by Puccianti, an excellent acquaintance with the techniques of X-ray diffraction. It was on this subject that Fermi carried out work for his bachelor dissertation, which he eventually presented in July 1922.

After his bachelor’s work, Fermi returned to Rome where he came in contact with Physics Institute director Orso Mario Corbino. Corbino succeeded in obtaining a scholarship for Fermi, which Fermi then used to finance a six-month stay in 1923 at Max Born’s school in Göttingen. Although this school probably had at the time the most progressive ideas towards the final formulation of quantum mechanics, Fermi did not find his stay particularly comfortable. The school’s excessive formal theoretical hypotheses, devoid of physical meaning, around which Born, Heisenberg, Jordan and Pauli were working, were not to his taste, and he preferred to work alone on some problems of analytical mechanics and statistical mechanics.

More intellectually stimulating, and fertile for scientific results, was Fermi’s second foreign visit one year later, thanks to a Rockefeller Foundation scholarship. From September to December 1924, Fermi worked at Leiden, at the institute directed by Paul Ehrenfest, where he found a much more congenial scientific atmosphere.

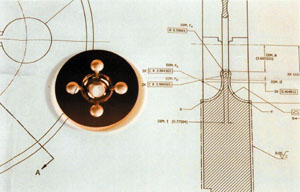

Between 1923 and 1925, Fermi published important contributions to quantum theory that culminated at the beginning of 1926 in the formulation of the antisymmetric statistics that are now universally known under the name Fermi-Dirac. In this fundamental work, Fermi took to their conclusion ideas that he had began to develop in Leiden on the statistical mechanics of an identical particle system, introducing the selection rule (Exclusion Principle) introduced by Pauli at the beginning of 1925, so as to construct a satisfactory theory of the behaviour of particles henceforth called fermions.

The far-sighted initiatives of Orso Mario Corbino for developing Italian physics bore their first fruits. In 1926 Corbino established a competitive chair of theoretical physics in Rome (the first of its kind in Italy), as a result of which Fermi gained a professorship at the institute in the via Panisperna at the age of 25.

The following September a major international physics convention took place in Como for a Volta commemoration.

It was during this convention that a demonstration, which was carried out by Sommerfeld and others, of the effectiveness of the new quantum statistics for the understanding of hitherto insoluble problems, ensured Fermi’s international reputation.

At the institute on the via Panisperna, a new collaboration began to take shape around Fermi and Rasetti at the beginning of 1927, as Corbino selected a group of promising young people. These included Edoardo Amaldi and Emilio Segrè.

By the end of the 1920s the “via Panisperna boys” switched from studying atomic and molecular spectroscopy to investigating the properties of the atomic nucleus – described by Corbino in a celebrated 1929 speech as the new frontier of physics.

This new line of research reflected Fermi’s growing scientific stature. In 1929 he was the only physicist designated to join the new Royal Academy of Italy. With this, and being secretary of the national physics research committee, he was able to steer funding and resources towards the new fields of research.

Nuclear summer

An important turning point was the first International Conference on Nuclear Physics, which was held in Rome in September 1931, and of which Fermi was both major organizer and scientific inspiration. Here, the main ongoing problems of nuclear physics were examined, which soon went on to be solved, notably in the “anno mirabile” of 1932 with the discovery of the neutron.

In the autumn of 1933, Fermi then added what is possibly his biggest contribution to physics – namely his milestone formulation of the theory of beta decay. In this formulation he took over the hypothesis of the neutrino, which had been postulated several years earlier by Pauli to maintain the validity of energy conservation in beta decay, and he used the idea that the proton and neutron are two different states of the same “fundamental object”, adding the radically new hypothesis that the electron does not pre-exist in the expelled nucleus but is liberated, with the neutrino, in the decay process, in an analogous way to the emission of a quantum of light resulting from an atomic quantum jump.

The theory also fitted in with the new formalism developed by Dirac in his quantum theory of radiation. It is interesting to note that Fermi’s work, which was initially sent to the Nature and was turned down because it was “too abstract and far from the physical reality”, was published elsewhere.

In 1934, nuclear physics research at via Panisperna capitalized on Frederic Joliot and Irene Curie’s discovery of artificial radioactivity. Fermi’s group discovered the radioactivity that is induced by neutrons, instead of the alpha particles of the Paris experiments, and soon they revealed the special properties of slow neutrons.

Sudden departure

Meanwhile the political situation in Italy began to give worrying signs of deterioration. While the major foreign laboratories began to invest in the new accelerators – fundamental machines to produce sources of controlled and intense subnuclear “bullets” to bombard the nuclei – Fermi’s attempts to obtain the necessary resources for an appropriately equipped national laboratory were not successful.

For a number of years, Fermi resisted numerous offers of posts in US universities. Then, in 1938, the promulgation of new racial laws threatened the Fermi family directly (Fermi’s wife, Laura Capon, was Jewish), so he took the decision to leave the country.

The opportunity to emigrate came with Fermi being awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics for his work on artificial radioactivity and slow neutrons. In December 1938 he received the prize in Stockholm and from there embarked with his family for the US and Columbia University in New York. Officially, he went to the US to deliver a series of lectures, but his friends knew that he had no intention of returning.

Wartime involvement

The discovery of nuclear fission and the outbreak of war dramatically highlighted the possible use of nuclear energy for military purposes. With his experience in neutron physics, Fermi was the natural leader for a group to carry out the first phase of a plan that would eventually lead to the atomic bomb – the achievement of a sustained and controlled chain reaction.

The work, which was classified as a military secret, was carried out in the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory. In December 1942 the first controlled fission chain reaction was achieved in the reactor constructed under Fermi’s direction. This led in turn to the Manhattan Project, in which Fermi had prominent roles, such as general adviser on theoretical issues, and finally as a member of the small group of scientists (with J Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence and Arthur Compton) that was charged with expressing technical opinions on the use of the new nuclear weapon.

In August 1944, Fermi moved to the village-laboratory of Los Alamos for the final development of the bomb, and in July 1945 he was among those who witnessed the first nuclear explosion in the Alamogordo desert.

Return to the laboratory

At the end of the Second World War, Fermi returned to Chicago and resumed his research in fundamental physics, at a time when new subnuclear particles were being discovered and when the new quantum electrodynamics was soon to appear.

In those years he led an influential research group, and a good number of the students associated with the group later went on to win Nobel prizes. The group continues to provide scientific advice for the US government.

Fermi, as a member of the General Advisory Committee, was against development work for a thermonuclear device, but this line met considerable resistance from Edward Teller, who went on, with mathematician Stan Ulam, to carry out much of the necessary theoretical work.

In this new context, Fermi developed an interest in possibilities that were being opened up by electronic computers, and in the early 1950s, in collaboration with Ulam, he carried out fundamental and pioneering work in the computer simulation of nonlinear dynamics.

Fermi returned twice to Italy. In 1949 he participated in a conference on cosmic rays in Como, which was the continuation of a series held earlier in Rome and Milan. Five years later, at the 1954 summer school of the Italian Physical Society in Varenna, he gave a memorable course on pion and nucleon physics.

On return to Chicago from this trip, he underwent surgery for a malignant tumour of the stomach, but he survived only a few weeks, dying on 29 November 1954.

Honouring a name

On 16 November 1954, on hearing that Enrico Fermi’s health had deteriorated, President Eisenhower and the US Atomic Energy Commission gave him a special award for a lifetime of accomplishments in physics and, in particular, for his role in the development of atomic energy. Fermi died soon after, on 29 November.

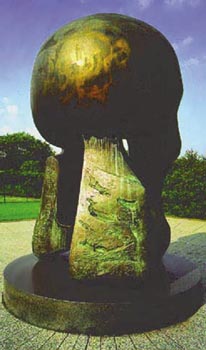

The Enrico Fermi US Presidential Award was subsequently established in 1956 to perpetuate the memory of Fermi’s brilliance as a scientist and to recognize others of his kind – inspiring others by his example.

Fermi’s memory is also perpetuated in the US through the Enrico Fermi Institute, as the department of the University of Chicago where he used to work is now known, and the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), which was named in his honour in 1974.

* This article was originally published in INFN Notizie, April 2001.

Centenary programme

In Italy the Fermi centenary is being marked by a series of meetings and events:

20 March – 28 April: exhibition on Fermi and Italian physics in Rome at the Ministry for the University and Research

2 July: Fermi, Master and Teacher, organized by the Italian Physical Society, for the opening of the 2001 courses of the Scuola Internazionale di Fisica “Enrico Fermi”, Varenna (Como)

29 September: opening of an exhibition, Enrico Fermi e l‚universo della Fisica, in Rome’s Teatro dei Dioscuri

29 September – 2 October: an international meeting, Enrico Fermi and the Universe of Physics, in Rome

3-6 October: an international meeting, Fermi and Astrophysics, at the International Center for Relativistic Astrophysics (ICRA), Pescara

18-20 October: an international meeting, Enrico Fermi and Modern Physics, organized by the Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, and Instituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Pisa

18-28 October: an exhibition, Enrico Fermi. Immagini e documenti inediti, organized by the Associazione per la diffusione della cultura scientifica “La Limonaia”, Pisa University’s Department of Physics, the town and local authorities, at the Limonaia di Palazzo Ruschi

22-23 October: a meeting, Enrico Fermi e l’energia nucleare, organized by Pisa University

In November: a meeting, Fermi e la meccanica statistica, organized by Pisa University’s Department of Physics.

In the US: 29 September: a Fermi centenary symposium at the University of Chicago.