On 21-24 September, in co-operation with several other scientific institutions, the Masaryk University in Brno is organizing

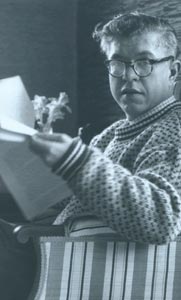

a memorial symposium in honour of the Czech physicist George Placzek, who was born on 26 September 1905 and died on 9 October 1955, soon after his 50th birthday. Placzek was an outstanding scientist who made substantial contributions to the fields of molecular physics, scattering of light from liquids and gases, the theory of the atomic nucleus and the interaction of neutrons with condensed matter. He belongs among the important physicists of the 20th century, setting an example not only through his discoveries, but also by the stimulating style of his scientific work.

George Placzek was born in Brno, Moravia, in what is now the Czech Republic but which in 1905 was part of Austro-Hungary. The oldest son of Alfred and Marianne Placzek, he spent his childhood in Brno and in Alexovice, where the family owned a textile factory, Skene & Co. He had a brother, Friedrich, one year younger and a sister, Edith, 12 years younger. The family was well integrated into the mixed Czech-German language environment around Brno. George studied in the Deutsches Staatsgymnasium in Brno between 1918 and 1924 and then went to the University of Vienna, with three semesters away in Charles University, Prague. He graduated in 1928, having defended his doctoral thesis, which dealt with the determination of density and shape of submicroscopic test bodies, with distinction.

Travels in Europe

In 1928, Placzek set off on several years of travel through the main scientific centres of Europe. This was usual for post-docs at the time, although Placzek later markedly avoided countries in which Adolf Hitler was increasingly encroaching upon civil liberties and human rights. He spent three years with Hendrik Kramers in Utrecht, followed in 1930-31 by a short time with Peter Debye and Werner Heisenberg in Leipzig. He then joined a group of young physicists led by Enrico Fermi in Rome, where Edoardo Amaldi became his closest colleague. Then, in 1932, Placzek joined Niels Bohr in Copenhagen where he remained until 1938, with periods of research fellowships or visiting professorships at the universities of Kharkov, Jerusalem, Paris and elsewhere.

Placzek’s first scientific interest was in the scattering of light from molecules and the Raman effect. With Lev Landau, he investigated the fine structure of a monochromatic wave in liquids and gases, and together they derived the Landau-Placzek formula for the ratio of intensities of Brillouin and Rayleigh scattering of light. Then in the early 1930s, the scattering of slow neutrons in matter became topical and Placzek was attracted to this problem, first in Rome and later in Copenhagen, where at Bohr’s suggestion he and Otto Frisch studied the capture of slow neutrons.

Placzek’s work in Copenhagen made him a leading authority on neutron scattering and absorption in matter. In a series of experiments, Placzek and Frisch discovered that the absorption of neutrons depends strongly on the atomic mass of the material and the velocity of the neutrons, while for slow neutrons and light elements the neutron-capture cross-section is inversely proportional to the velocity. He also worked with Hans Bethe on a theory of neutron absorption resonances, deriving important laws and selection rules, and publishing a seminal paper on resonance reactions in 1937. Papers published later by Placzek with Bohr and Rudolf Peierls dealt with the general theory of nuclear reactions and rank among the classics. For example, the well-known optical theorem, connecting the imaginary part of a scattering amplitude with the total cross-section, bears the names of Bohr, Peierls and Placzek. Using the optical theorem and Bohr’s drop model of the nucleus, the trio developed a fundamental theory of neutron-induced nuclear reactions.

Hitler’s preparations for a systematic occupation of all countries bordering Germany endangered some members of Bohr’s international team, including Placzek. The Anschluss of Austria in the spring of 1938 and the seizing of a large region from Czechoslovakia through the Munich treaty in September of that year left no-one in the dark. Bohr decided to move part of his Copenhagen Institute to the other side of the Atlantic. Placzek left Copenhagen for the US in January 1939 and in Princeton, at the beginning of February, he met Bohr, who had been waiting for him impatiently.

Across the Atlantic

Placzek’s first encounter with Bohr on the other side of the Atlantic provides an interesting illustration of their personal relationship and scientific collaboration. While sources (e.g. Moore 1966, Wheeler and Ford 2000) do not agree exactly on what was discussed during breakfast on 3 February 1939, they do seem to have the same opinion on the following. Bohr found Placzek – “the institute’s always stimulating Bohemian” – sitting with Leon Rosenfeld. Their discussion focused on some exciting news from Europe. First, Frisch and Lise Meitner had recently suggested that most of the transuranic elements were produced by a new type of nuclear reaction – the capture of neutrons from uranium fission. Second, Placzek had suggested to Frisch in Copenhagen how he might confirm the existence of fission in a straightforward way, which Frisch promptly did on 13 January 1939.

Bohr, listening attentively, looked up with a big smile: “For one good thing, we’re free of transuranic elements.” Placzek, the sceptic, 20 years younger than Bohr, commented: “Yes, but now you’re in a worse mess. How can you reconcile it with your view of nuclear reactions?”. How, he asked, was Bohr going to explain why slow rather than fast neutrons should cause uranium to fission? Why should slow neutrons induce a modest fissioning in uranium, but be captured in thorium?

Bohr suddenly went pale, took Rosenfeld and set off across the campus to his office. He went to the blackboard and worked rapidly, making some rough sketches. In about ten minutes he stopped; he had the answer to the problem posed by Placzek, related to the fissioning of the nuclei. The fission cross-section for slow neutrons must be due to the small amount of the isotope uranium-235, the cross-section increasing as the wavelength of the neutrons increases with decreasing energy.

From 1939 to 1942 Placzek was professor at Cornell University, Ithaca. Later he went to Montreal and Los Alamos, where he contributed to solving problems related to the moderation of neutrons in matter. He was apparently the only citizen of Czechoslovakia to take part in the Manhattan Project, being head of the Theory Group in Chalk River near Montreal, and then in Los Alamos from May 1945. Later he worked for some time in the General Electric Company in Schenectady and in 1948, he obtained a permanent position at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.

In the last years of his life, Placzek went into more depth with his analysis of the elastic and inelastic scattering of light particles in liquids and crystals, aimed at investigating the physical properties of these media. Albert Messiah and Léon Van Hove were among his collaborators and friends in this period (Van Hove 1956, Messiah 1991). During this time, he also visited Europe to lecture on the moderation and diffusion of neutrons and in 1954, the book Introduction to the Theory of Neutron Diffusion, by K M Case, F de Hoffmann and Placzek appeared, based on a lecture course Placzek gave in Santa Monica and Los Angeles in the summer of 1949. In autumn 1955, Placzek died in Zurich while he was planning a several-month lecture tour through Italy for the academic year 1955-56.

During his scientific career, Placzek provided a quantum formulation of Raman light scattering, developed the ideas of molecular symmetry and its application in physics, and in collaboration with Bethe, Bohr and Peierls, contributed to the general theory of nuclear reactions. He systematically studied the behaviour of neutrons in nuclear reactions, neutron resonances, scattering and diffusion in matter, and the moderation and absorption of neutrons in crystals and liquids. He was among the first to suggest, independently of several others, that graphite might be used to moderate neutrons. Yet his name is not well known.

The importance of publication

Those who knew Placzek personally agree that his discoveries and results in physics, rich and important as they were, were not sufficiently published; only a small portion of his results appeared in print. As Van Hove points out, Landau’s and Placzek’s classic results on the scattering of a monochromatic wave in liquids were published in an incomplete form, and were only later discussed in more detail by Jacov Frenkel in his Kinetic Theory of Liquids. The same holds for the results on the general theory of nuclear reactions obtained by Bohr, Peierls and Placzek. Amaldi wrote about Placzek in 1956: “The redaction of an article represented an immense effort for him; even important results of his, which he had formulated clearly and in definite form, often remained unpublished.”

He was noted for strict moral principles and a great sense of tolerance

Edoardo Amaldi

This trait of Placzek’s corresponded to his desire always to deepen his analyses of the phenomena he studied. Moreover, many of his original ideas are implicitly contained in other papers. As an unmerciful critic, Placzek often served as the scientific conscience for his colleagues, stimulating their invention, criticizing their work and forcing them to formulate their scientific ideas clearly. He had a number of characteristics that made him a welcome collaborator and team member: a highly developed critical sense, an ability to understand new problems quickly and to confront them with relevant facts, an unselfish willingness to offer advice and, last but not least, a generous disinterest in participating in the result.

These attributes, as Amaldi explains, reflected Placzek’s character. He excelled in general erudition and in a culture anchored in fundamental ideas. He easily learned foreign languages and felt great affection for small nations. He was noted for strict moral principles and a great sense of tolerance.

What little remains

Despite Placzek’s long collaboration with Bohr there are only a few photographs and letters in the Niels Bohr Archive in Copenhagen. One possible explanation is that, before moving to America, Bohr obliterated all traces that could help the Nazis pursue the families of those who had fled from occupied countries. In Placzek’s fatherland, by the end of 2004, only a few documents had been found: a note in the register of births (containing the names of his parents and grandparents, the godfathers, the rabbi and the midwife), the regular notes of his studies in the Staatsgymnasium high school, and the distasteful entries in the book of the right of domicile. Placzek’s parents and his sister died in concentration camps during the Second World War, while his brother died eight days after the Nazis’ invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939. Recently, however, in connection with the double anniversary of Placzek’s birth and death, many interesting documents have been found about his relatives and the history of the whole family in Moravia and North America (Gottvald 2005). These will be presented at the symposium.

<textbreak=Acknowledgements>

The author is greatly indebted to Ugo Amaldi, Giuseppe Cocconi, Torleif Ericson, Ales Gottvald, André Martin, Michelle Mazerand, Jack Steinberger, Valentin Telegdi and Jenny Van Hove for providing valuable information relating to George Placzek.