Image credit: Photographie Benjamin Couprie, Institut International de Physique Solvay, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives.

Our story begins in 1911, with the first International Women’s Day celebrated in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland. That same year, Marie Skłodowska-Curie won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of two new elements: radium and polonium. This was the second time that she had been called to Stockholm – eight years earlier, she received the Nobel Prize in Physics, which she and her husband Pierre Curie shared with Henri Becquerel for their research on radioactivity. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry has only been awarded to three other women: Curie’s daughter Irène Joliot-Curie in 1935, Dorothy Crowfoot-Hodgkin in 1964 and Ada Yonath in 2009. The only other woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Physics is Maria Goeppert Mayer for her work on the structure of atomic nuclei (1963).

Marie Curie achieved several “firsts”. She was the first woman to receive the Nobel Prize (in 1903), the first person to receive it twice, the first female professor at the University of Paris and, as the photograph on this page shows, the only female among the 24 participants at the first international physics conference – the Solvay Conference – held in Brussels in 1911. A century later, the situation has changed. At the recent -International Conference on High-Energy Physics, ICHEP2010, 15.4% of the participants were women.

Nuclear physics pioneers

The 1940s and 1950s were exciting years in physics. The first accelerators were being built, and with them physicists took the first steps towards the current understanding of particle physics. At this challenging time after the Second World War, many women joined physics groups around the world and helped to open doors for the future generations of women in science.

Marietta Blau (1894–1970) pioneered work in photographic methods to study particle tracks and was the first to use nuclear emulsions to detect neutrons by observing recoil protons. Her request for a better position at Vienna University was rejected because she was a woman and a Jew. Blau left Austria and was appointed professor in Mexico City after the war. She was nominated for the Nobel Prize several times.

Nella Mortara (1893–1988), one of the most beloved assistant professors of physics at the University of Rome in the late 1930s, faced a similar ordeal and was expelled for being Jewish. She escaped to Brazil but returned secretly during the war to be reunited with her family in Rome, living in great danger. After the war Mortara was reappointed as a professor, to the great joy of her students, many of whom were women.

Lise Meitner (1878–1968) also suffered from this double discrimination. She became the second woman to obtain a PhD from Vienna in 1903. She moved to Berlin where she was “allowed” by Max Planck to attend his lectures – the first woman to be granted this privilege – and then later became his assistant. Many believe that Meitner should have been co-awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Otto Hahn in 1944 for the discovery of nuclear fission. She had the courage to refuse to work on the Manhattan Project, saying: “I will have nothing to do with a bomb!”

Maria Goeppert Mayer (1906–1972) lectured at prestigious universities, published numerous papers on quantum mechanics and chemical physics, and collaborated with her husband on an important textbook. Despite her accomplishments, antinepotism rules forbade Mayer from receiving an official post and for many years she taught physics at universities as an unpaid volunteer. Finally, in 1959, four years before receiving the Nobel Prize, the University of California at San Diego offered her a full-time position.

Leona Marshall Libby (1919–1986) was an innovative developer of nuclear technology. She built the tools that led to the discovery of cold neutrons and she also investigated isotope ratios. Libby was the first woman to be part of Enrico Fermi’s team for the Manhattan Project and eventually became professor of physics at that institution, leaving a legacy of exploration and innovation.

Closer to particle physics, Hildred Blewett (1911–2004) was an accelerator physicist from Brookhaven. In the early 1950s she contributed to the design of CERN’s first high-energy accelerator, the Proton Synchrotron, while also working on a similar machine proposed for Brookhaven.

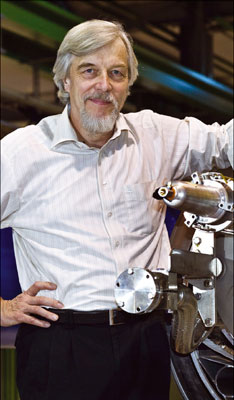

Maria Fidecaro has spent her life dedicated to her research at CERN, where she still works. She arrived at CERN in 1956 after working in Rome on cosmic-ray experiments and, for a year, at the synchrocyclotron in Liverpool. Maria remembers fondly what it was like to be a physics student just after the war, the challenges of balancing a career with family and collaborating with other pioneers of modern physics from all over the world, including many women. “I remained dedicated to research throughout the changing circumstances,” she says, “and always to the best of my ability.”

These are just a few of the women physicists who were around during the mid-20th century; courageous women dedicated to their science, they served as role models for later generations.

Women and the growth of CERN

CERN was founded in 1954 during the post-war period of renewal. The CERN Convention was very modern because it mentioned all of the professional categories needed to form a large international organization such as that which exists today. Women were initially recruited in supportive administrative positions, but this changed as they began to enter all areas of university training, physics and technical professions. CERN was willing to provide and encourage working opportunities for women, which they needed to be able to flourish in these new areas.

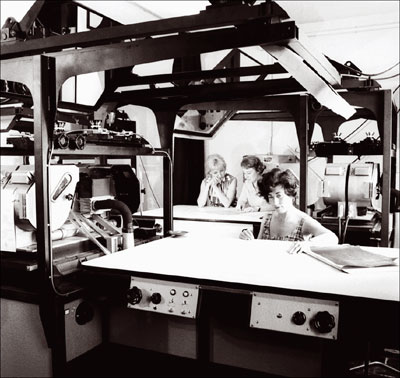

Between the 1960s and the mid-1980s, dozens of women worked at CERN and elsewhere as scanners. Their job consisted of finding interesting events among the many tracks left by particles in bubble chambers and captured on photographs. Madeleine Znoy recalls how tedious it was: “Initially, the work was done manually, using a pencil and a sheet of paper to note down the co-ordinates where the interactions had taken place. Scanning took place round the clock, because the quantity of films to be scanned was enormous. From 7.00 am to 10.00 p.m., female scanners studied the films, and from 10.00 p.m. until 7.00 a.m., men (often students) took over,” she explains. Each shift lasted only four hours due to the work being so strenuous, working in complete darkness with three projectors illuminating the film. Znoy once beat a record, scanning more than 750 photographs in one day. “At first, some physicists thought that this was impossible, that surely I had missed interesting events. But all was fine and they were very surprised!”

Anita Bjorkebo started as a scanner in 1965. After her scanning shift she compiled data and classified events, all by hand, and even made the histograms.

Later, as scanning became more automated, the scanners moved on to operating the computers connected to the measuring equipment. Some, including Bjorkebo and Znoy, would set them up for other scanners or streamline the operation for new experiments. Bjorkebo became so interested in her work that she signed up for two particle-physics classes, attending lectures and doing homework after work. “A Swedish physicist only had five students here so he invited the technical staff to join in,” she explains.

Even though these women did not get their names on publications, they felt appreciated. “We were part of the team, we had a role to play,” says Znoy proudly. “With the scanning, we could really see the particles. I really enjoyed working with the physicists and technicians, and collaborating with other laboratories. We were young and full of enthusiasm. It was a great period.”

Nevertheless, after more than 50 years, the situation for women at CERN could still be improved, especially in the intermediate administrative categories where they are most represented. Recruitment in this area is now often based on standardized job criteria that leave less room to appreciate the level of education and professional skills needed for a post. However, the administrative staff category is essential to the day-to-day life of CERN. To function properly CERN depends on good communication within the organization, the dedication of its staff and proper advancement prospects at all levels. Danièle Lajust, an administrative assistant who joined CERN in 1978, is quick to add: “We are proud of belonging to an organization that now welcomes a gender mix at all levels and of participating in our own way in its great and passionate adventure.”

Showing the way

CERN also has an important part to play in educating young scientists and hence providing role models. In 2000, Melissa Franklin, an alumna of the CERN Summer Student programme in 1977, returned as a lecturer on Classic Experiments. She then became the first tenured female professor of physics at Harvard University, and now works on the ATLAS experiment at CERN. Franklin’s is just one of the many amazing careers experienced by former CERN summer students.

Started in 1962 by the then director-general of CERN, Viki Weisskopf, the Summer Student programme began with just 70 students. Nowadays, walk through any of the buildings at CERN in mid-July and you can see evidence of about 140 students participating in the programme. Although half of the students today are women, there are still only a handful of female lecturers – in 2010, only three of the 31 lecturers were women. Providing the summer students with adequate role models is just as important as enhancing diversity in their ranks, because the teachers, authors and educators that we encounter have a great influence on our lives and careers.

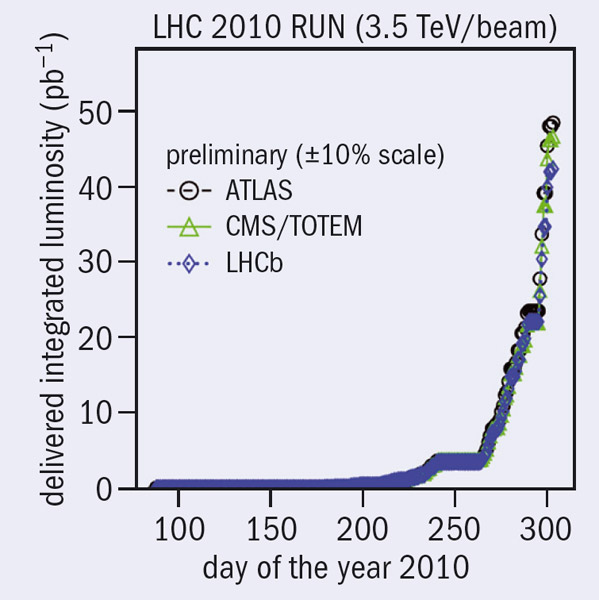

Today, women make up about 17% of the many thousand scientists, engineers and technicians who work on the LHC experiments, from graduate students to full professors. Nearly half of these women are students or post-docs, showing that more women are joining the field.

The day-to-day operation of the LHC is in the hands of eight “engineers in charge”, half of whom are women. One of them, Giulia Papotti, thanks the management for having an open mind: “They were looking for someone with radio-frequency expertise, which is my field. Other considerations such as nationality or gender were secondary.” It proved to be the greatest challenge of her career, training to be an LHC operator during the high-intensity period of the first days of operation. “I had to learn fast,” she recalls. The workload was additionally taxing because two people were still in training and two were on parental leave. “Our work is to think about how to improve things. We are meant to be critical. We are paid to think,” says Papotti.

Amalia Ballarino, a scientist working on superconductivity, designed and managed the production of the high-temperature superconducting components that power the LHC magnets. For this work she won the international Superconductor Industry Person of the Year award in 2006 (p37). “We had to work to a tight schedule,” she says of building a system that consists of 3000 components made across the world. “Working at CERN gives you the opportunity to contribute to innovative projects. Basic science is the primary driver of innovation.” Ballarino adds: “Working here is an opportunity to create something new.” Lene Norderhaug, a CERN fellow working on software development and looking towards the future says enthusiastically: “In five years I hope to have my PhD and my second job at CERN. We like it here!”

Women in science have been passionate about their chosen field, undertaking tasks with great responsibility and continuously striving to push science and technology beyond their limits. Looking back on 100 years of International Women’s Day, we have progressed from just one woman at a conference to females representing 17% of the field. What will the next 100 years bring?