In October 2007, neutrino physicists broke ground 55 km north-east of Hong Kong to build the Daya Bay Reactor Neutrino Experiment. Comprising eight 20-tonne liquid-scintillator detectors sited within 2 km of the Daya Bay nuclear plant, its aim was to look for the disappearance of electron antineutrinos as a function of distance to the reactor. This would constitute evidence for mixing between the electron and the third neutrino mass eigenstate, as described by the parameter θ13. Back then, θ13 was the least well known angle in the Pontecorvo–Maki–Nakagawa–Sakata matrix, which quantifies lepton mixing, with only an upper limit available. Today, it is the best known angle by some margin, and the knowledge that it is nonzero has opened the door to measuring leptonic CP violation at long-baseline accelerator-neutrino experiments.

Daya Bay was one of a trio of experiments located in close proximity to nuclear reactors, along with RENO in South Korea and Double Chooz in France, which were responsible for this seminal measurement. Double Chooz published the first hint that θ13 was nonzero in 2011, before Daya Bay and RENO established this conclusively the following spring. The experiments also failed to dispel the reactor–antineutrino anomaly, whereby observed neutrino fluxes are a few percent lower than calculations predict. This has triggered a slew of new experiments located mere metres from nuclear-reactor cores, in search of evidence for oscillations involving additional, sterile light neutrinos. As the Daya Bay experiment’s detectors are dismantled, after almost a decade of data taking, the three collaborations can reflect on the rare privilege of having pencilled the value of a previously unknown parameter into the Standard- Model Lagrangian.

Particle physics is fundamental and influential, and deserves to be supported

Yi-Fang Wang

Founding Daya Bay co-spokesperson Yi-Fang Wang says the experiment has had a transformative effect on Chinese particle physics, emboldening the country to explore major projects such as a circular electron–positron collider. “One important lesson we learnt from Daya Bay is that we should just go ahead and do it if it is a good project, rather than waiting until everything is ready. We convinced our government that we could do a great job, that world-class jobs need to be international, and that particle physics is fundamental and influential, and deserves to be supported.”

JUNO

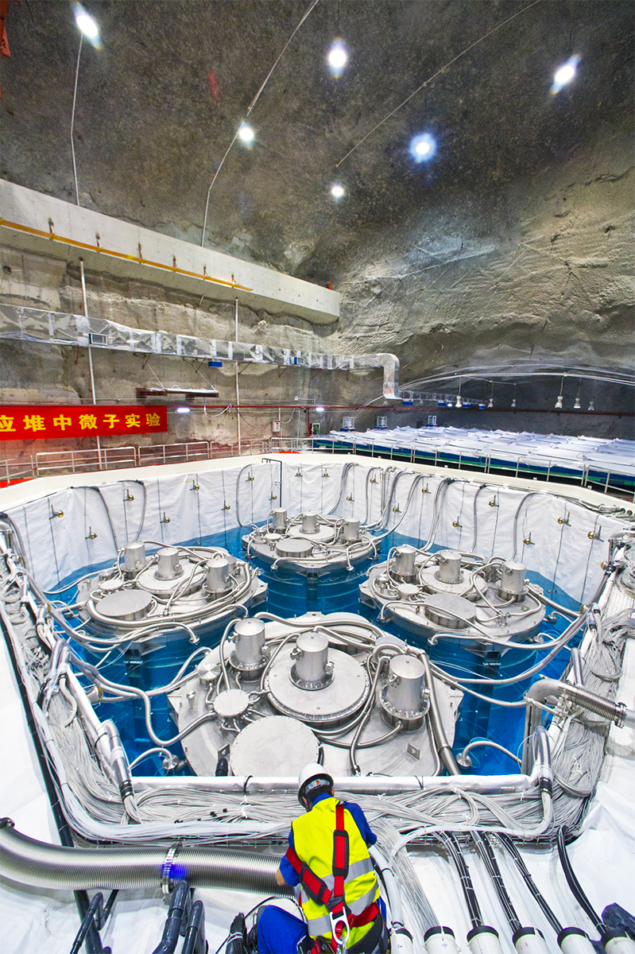

The experiment has also paved the way for China to build a successor, the Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory (JUNO), for which Wang is now spokesperson. JUNO will tackle the neutrino mass hierarchy – the question of whether the third neutrino mass eigenstate is the most or least massive of the three. An evolution of Daya Bay, the new experiment will also measure a deficit of electron antineutrinos, but at a distance of 53 km, seeking to resolve fast and shallow oscillations that are expected to differ depending on the neutrino mass hierarchy. Excavation of a cavern for the 20 kilotonne liquid-scintillator detector 700 m beneath the Dashi hill in Guangdong was completed at the end of 2020. The construction of a concrete water pool is the next step.

The next steps in reactor-neutrino physics will involve an extraordinary miniaturisation

Thierry Lasserre

The detector concept that the three experiments used to uncover θ13 was designed by the Double Chooz collaboration. Thierry Lasserre, one of the experiment’s two founders, recalls that it was difficult, 20 years ago, to convince the community that the measurement was possible at reactors. “It should not be forgotten that significant experimental efforts were also undertaken in Angra dos Reis, Braidwood, Diablo Canyon, Krasnoyarsk and Kashiwazaki,” he says. “Reactor neutrino detectors can now be used safely, routinely and remotely, and some of them can even be deployed on the surface, which will be a great advantage for non-proliferation applications.” The next steps in reactor-neutrino physics, he explains, will now involve an extraordinary miniaturisation to cryogenic detectors as small as 10 grams, which take advantage of the much larger cross section of coherent neutrino scattering.