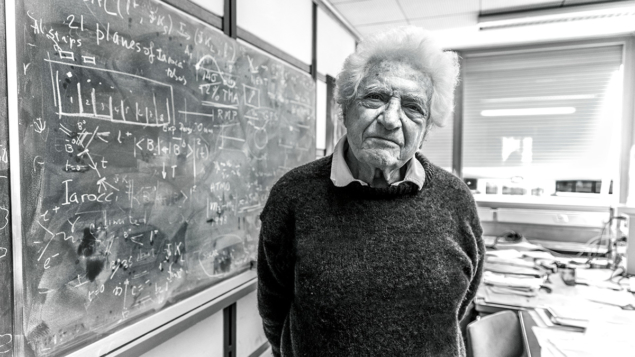

Jack Steinberger, a giant of the field who witnessed and shaped the evolution of particle physics from its beginnings to the confirmation of the Standard Model, passed away on 12 December aged 99. Born in the Bavarian town of Bad Kissingen in 1921, his father was a cantor and religious teacher to the small Jewish community, and his mother gave English and French lessons to supplement the family income. In 1934, after new Nazi laws had excluded Jewish children from higher education, Jack’s parents applied for him and his brother to take part in a charitable scheme that saw 300 German refugee children transferred to the US. Jack found his home as a foster child, and was reunited with his parents and younger brother in 1938.

Jack studied chemistry at the University of Chicago until 1942, when he joined the army and was sent to the MIT radiation laboratory to work on radar bomb sights. He was assigned to the antenna group where his attention was brought to physics. After the war he returned to Chicago to embark on a career in theoretical physics. Under the guidance of Enrico Fermi, however, he switched to the experimental side of the field, conducting mountaintop investigations into cosmic rays. He was awarded a PhD in 1948. Fermi, who was probably Jack’s most influential physics teacher, described him as “direct, confident, without complication, he concentrated on physics, and that was enough”.

In 1949 Steinberger went to the Radiation Lab at the University of California at Berkeley, where he performed an experiment at the electron synchrotron that demonstrated the production of neutral pions and their decay to photon pairs. He stayed only one year in Berkeley, partly because he declined to sign the anti-communist loyalty oath, and moved on to Columbia University.

In the 1960s the construction of a high-energy, high-flux proton accelerator at Brookhaven opened the door to the study of weak interactions using neutrino-beam experiments. This marked the beginning of Jack’s interest in neutrino physics. Along with Mel Schwarz and Leon Lederman, he designed and built the experiment that established the difference between neutrinos associated with muons and those associated with electrons, for which they received the 1988 Nobel Prize in Physics.

He was a curious and imaginative physicist with an extraordinary rigour

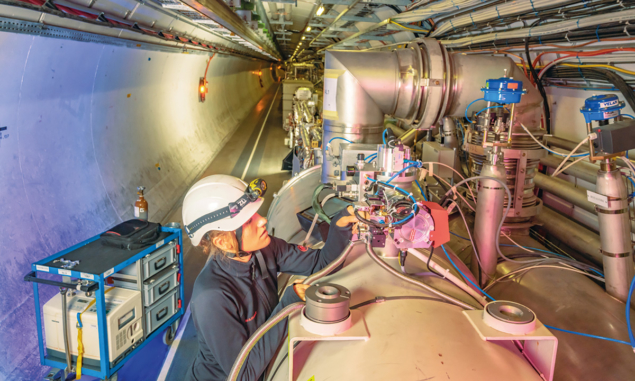

Jack joined CERN in 1968, working on experiments at the Proton Synchrotron exploring CP violation in neutral kaons. In the 1970s, with the advent of new neutrino beams at the Super Proton Synchrotron, Jack became a founding member of the CERN–Dortmund–Heidelberg–Saclay (CDHS) collaboration. Running from 1976 to 1984, CDHS produced a string of important results using neutrino beams to probe the structure of the nucleon and the Standard Model in general. In particular, the collaboration confirmed the predicted variation of the structure function of the valence quarks with Q2 (nicknamed “scaling violations”), a milestone in the establishment of QCD.

When the Large Electron–Positron (LEP) collider was first proposed, a core group from CDHS joined physicists from other institutions to develop a detector for CERN’s new flagship collider. This initiative grew into the ALEPH experiment, and Jack, a curious and imaginative physicist with an extraordinary rigour, was the natural choice to become its first spokesperson in 1980, a position he held until 1990. From the outset, he stipulated that standard solutions should be adopted across the whole detector as far as possible. This led to the end-caps reflecting the design of the central detector, for example. Jack was also insistent that all technologies considered for the detector first had to be completely understood. As the LEP era got underway, this level of discipline was reflected in ALEPH’s results.

Next to physics, music formed an important part of Jack’s life. He organised gatherings of amateur, and occasionally professional, musicians at his house. These were usually marathons of Bach, starting in the late afternoon and continuing until the late evening. In his autobiography, Jack summarised: “I play the flute, unfortunately not very well, and have enjoyed tennis, mountaineering and sailing, passionately.”

Jack retired from CERN in 1986 and went on to become a professor at the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. President Ronald Reagan awarded him the National Medal of Science in 1988. In 2001, on the occasion of his 80th birthday, the city of Bad Kissingen named its gymnasium in his honour. Jack continued his association with CERN throughout his 90s. He leaves his mark not just on particle physics but on all of us who had the opportunity to collaborate with him.