Since the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, the ATLAS and CMS collaborations have made significant progress in scrutinising its properties and interactions. So far, measurements are compatible with an elementary Higgs boson, originating from the minimal scalar sector required by the Standard Model. However, current experimental precision leaves ample room for this picture to change. In particular, the full potential of the LHC and its high-luminosity upgrade to search for a richer scalar sector beyond the Standard Model (BSM) is only beginning to be tapped.

The first Workshop on the Impact of Higgs Studies on New Theories of Fundamental Interactions, which took place on the Island of Capri, Italy, from 6 to 10 October 2025, gathered around 40 experimentalists and theorists to explore the pivotal role of the Higgs boson in exploring BSM physics. Participants discussed the implications of extended scalar sectors and the latest ATLAS and CMS searches, including current potential anomalies in LHC data.

“The Higgs boson has moved from the realm of being just a new particle to becoming a tool for searches for BSM particles,” said Greg Landsberg (Brown University) in an opening talk.

An extended scalar sector can address several mysteries in the SM. For example, it could serve as a mediator to a hidden sector that includes dark-matter particles, or play a role in generating the observed matter–antimatter asymmetry during an electroweak phase transition. Modified or extended Higgs sectors also arise in supersymmetric and other BSM models that address why the 125 GeV Higgs boson is so light compared to the Planck mass – despite quantum corrections that should drive it to much higher scales – and might shed light on the perplexing pattern of fermion masses and flavours.

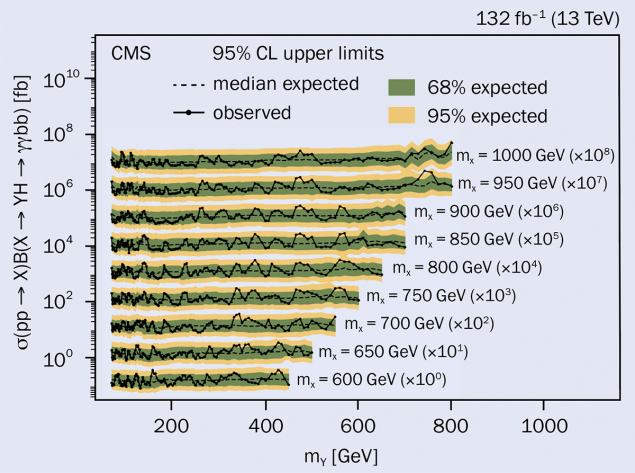

One way to look for new physics in the scalar sector is modifications in the decay rates, coupling strengths and CP-properties of the Higgs boson. Another is to look for signs of additional neutral or charged scalar bosons, such as those predicted in longstanding two-Higgs-doublet or Higgs-triplet models. The workshop saw ATLAS and CMS researchers present their latest limits on extended Higgs sectors, which are based on an increasing number of model-independent or signature-based searches. While the data so far are consistent with the SM, a few mild excesses have attracted the attention of some theorists.

In diphoton final states, a slight excess of events persists in CMS data at a mass of 95 GeV. Hints of a small excess at a mass of 152 GeV are also present in ATLAS data, while a previously reported excess at 650 GeV has faded after full examination of Run 2 data. Workshop participants also heard suggestions that the Brout–Englert–Higgs potential could allow for a second resonance at 690 GeV.

The High-Luminosity LHC will enable us to explore the scalar sector in detail

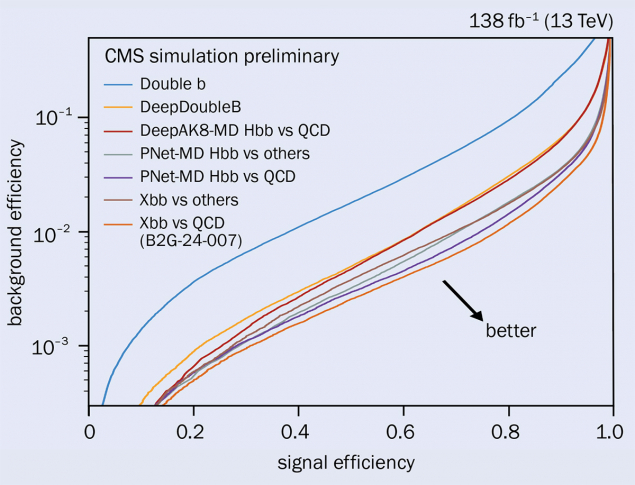

“We haven’t seen concrete evidence for extended Higgs sectors, but intriguing features appear in various mass scales,” said CMS collaborator Sezen Sekmen (Kyungpook National University). “Run 3 ATLAS and CMS searches are in full swing, with improved triggering, object reconstruction and analysis techniques.”

Di-Higgs production, the rate of which depends on the strength of the Higgs boson’s self-coupling, offers a direct probe of the shape of the Brout–Englert–Higgs potential and is a key target of the LHC Higgs programme. Multiple SM extensions predict measurable effects on the di-Higgs production rate. In addition to non-resonant searches in di-Higgs production, ATLAS and CMS are pursuing a number of searches for BSM resonances decaying into a pair of Higgs bosons, which were shown during the workshop.

Rich exchanges between experimentalists and theorists in an informal setting gave rise to several new lines of attack for physicists to explore further. Moreover, the critical role of the High-Luminosity LHC to probe the scalar sector of the SM at the TeV scale was made clear.

“Much discussed during this workshop was the concern that people in the field are becoming demotivated by the lack of discoveries at the LHC since the Higgs, and that we have to wait for a future collider to make the next advance,” says organiser Andreas Crivellin (University of Zurich). “Nothing could be further from the truth: the scalar sector is not only the least explored of the SM and the one with the greatest potential to conceal new phenomena, but one that the High-Luminosity LHC will enable us to explore in detail.”