On a recent visit to CERN, I had the chance to see how the high-energy physics (HEP) community was struggling with many of the same sorts of computing problems that we have to deal with at Google. So here are some thoughts on where commodity computing may be going, and how organizations like CERN and Google could influence things in the right direction.

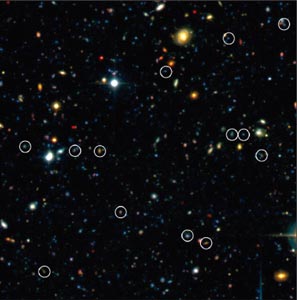

First a few words about what we do at Google. The Web consists of more than 10 billion pages of information. With an average of 10 kB of textual information per page, this adds up to around 100 TB. This is our data-set at Google. It is big, but tractable – it is apparently just a few days’ worth of data production from the Large Hadron Collider. So just like particle physicists have already found out, we need a lot of computers, disks, networking and software. And we need them to be cheap.

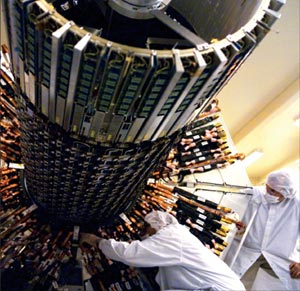

The switch to commodity computing began many years ago. The rationale is that single machine performance is not that interesting any more, since price goes up non-linearly with performance. As long as your problem can be easily partitioned – which is the case for processing Web pages or particle events – then you might as well use cheaper, simpler machines.

But even with cheap commodity computers, keeping costs down is a challenge. And increasingly, the challenge is not just hardware costs, but also reducing energy consumption. In the early days at Google – just five years ago – you would have been amazed to see cheap household fans around our data centre, being used just to keep things cool. Saving power is still the name of the game in our data centres today, even to the extent that we shut off the lights in them when no-one is there.

Let’s look more closely at the hidden electrical power costs of a data centre. Although chip performance keeps going up, and performance per dollar, too, performance per watt is stagnant. In other words, the total power consumed in data centres is rising. Worse, the operational costs of commercial data centres are almost directly proportional to how much power is consumed by the PCs. And unfortunately, a lot of that is wasted.

For example, while the system power of a dual-processor PC is around 265 W, cooling overhead adds another 135 W. Over four years, the power costs of running a PC can add up to half of the hardware cost. Yet this is a gross underestimate of real energy costs. It ignores issues such as inefficiencies of power distribution within the data centre. Globally, even ignoring cooling costs, you lose a factor of two in power from the point where electricity is fed into a data centre to the motherboard in the server.

Since I’m from a dotcom, an obvious business model has occurred to me: an electricity company could give PCs away – provided users agreed to run the PCs continuously for several years on the power from that company. Such companies could make a handsome profit!

A major inefficiency in the data centre is DC power supplies, which are typically about 70% efficient. At Google ours are 90% efficient, and the extra cost of this higher efficiency is easily compensated for by the reduced power consumption over the lifetime of the power supply.

Part of Google’s strategy has been to work with our component vendors to get more energy-efficient equipment to market earlier. For example, most motherboards have three DC voltage inputs, for historical reasons. Since the processor actually works at a voltage different from all three of these, this is very inefficient. Reducing this to one DC voltage produces savings, even if there are initial costs involved in getting the vendor to make the necessary changes to their production. The HEP community ought to be in a similar position to squeeze extra mileage out of equipment from established vendors.

Tackling power-distribution losses and cooling inefficiencies in conventional data centres also means improving the physical design of the centre. We employ mechanical engineers at Google to help with this, and yes, the improvements they make in reducing energy costs amply justify their wages.

While I’ve focused on some negative trends in power consumption, there are also positive ones. The recent switch to multicore processors was a successful attempt to reduce processors’ runaway energy consumption. But Moore’s law keeps gnawing away at any ingenious improvement of this kind. Ultimately, power consumption is likely to become the most critical cost factor for data-centre budgets, as energy prices continue to rise worldwide and concerns about global warming put increasing pressure on organizations to use electrical power more efficiently.

Of course, there are other areas where the cost of running data centres can be greatly optimized. For example, networking equipment lacks commodity solutions, at least at the data-centre scale. And better software to turn unreliable PCs into efficient computing platforms can surely be devised.

In general, Google’s needs and those of the HEP community are similar. So I hope we can continue to exchange experiences and learn from each other.