The HERA facility at DESY was unique: it was the only accelerator in the world to collide electrons (or positrons) with protons, at centre-of-mass energies of 240–320 GeV. In collisions such as these, the point-like electron “probes” the interior of the proton via the electroweak force, while acting as a neutral observer with regard to the strong force. This made HERA a precision machine for QCD – a “super electron microscope” designed to measure precisely the structure of the proton and the forces within it, particularly the strong interaction. HERA’s point-like probes also gave it an advantage over proton colliders such as the LHC: while protons can have a much higher energy, they are composite particles dominated by the strong force, which makes it much more difficult to use them to resolve the proton’s structure. The results from HERA, many of which are already part of textbook knowledge, promise to remain valid and unchallenged for quite some time.

Into the depths of the proton

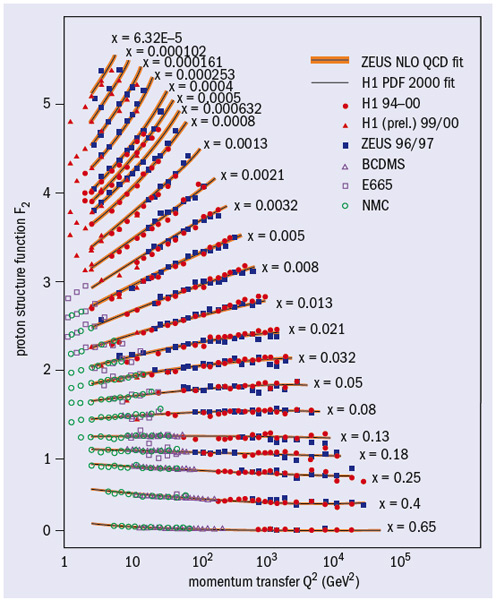

The proton’s structure can be described by using various structure functions, each of which covers different aspects of the electron–proton interaction. HERA was the world’s only accelerator where physicists could study the three structure functions of the proton in detail. During the first phase of operation (HERA I), the colliding-beam experiments H1 and ZEUS already provided surprising new insights into F2, which describes the distribution of the quarks and antiquarks as a function of the momentum transfer (Q2) and the momentum fraction (x) of the proton’s total momentum. When HERA started up in 1992, physicists already knew that the quarks in the proton emit gluons, which give rise to other gluons and to quark–antiquark pairs in the virtual “sea”. However, the general assumption was that, apart from the three valence quarks, there were only very few quark–antiquark pairs and gluons in the proton.

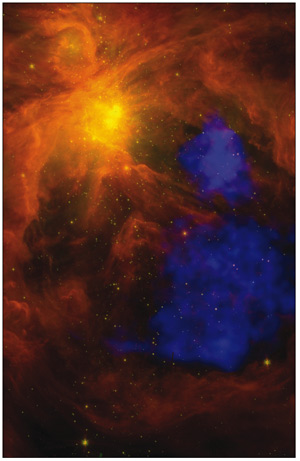

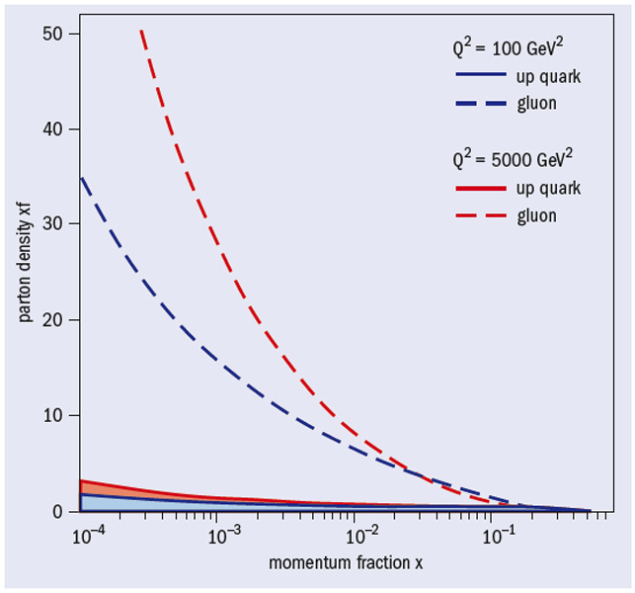

Thanks to HERA’s high centre-of-mass energy, H1 and ZEUS pushed forward to increasingly shorter distances and smaller momentum fractions, and measured F2 over a range that spans four orders of magnitude of x and Q2 – two to three orders of magnitude more than were accessible with earlier experiments (figure 1). What the two experiments discovered came as a great surprise: the smaller the momentum fraction, the greater the number of quark–antiquark pairs and gluons that appear in the proton (figure 2). The interior of the proton therefore looks much like a thick, bubbling soup in which gluons and quark–antiquark pairs are continuously emitted and annihilated. This high density of gluons and sea quarks, which increases at small x, represented a completely new state of the strong interaction – which had never been investigated until then.

The proton sea, however, comprises not only up, down and strange quarks. Thanks to the high luminosity achieved during HERA’s second operating phase (HERA II), the experiments for the first time revealed charm and bottom quarks in the proton, with charm quarks accounting for 20–30% of F2 in some areas, and bottom quarks accounting for 0.3–1.5%. It appears that all quark flavours are produced democratically at extremely high momentum-transfers, where even the mass of the heavy quarks becomes irrelevant. The analysis of the remaining data will further enhance the precision and lead to a better understanding of the generation of heavy quarks, which is particularly important for physics at the LHC.

During HERA II, H1 and ZEUS also used longitudinally polarized electrons and positrons. This boosted the experiments’ sensitivity for the structure function xF3, which describes the interference effects between the electromagnetic and weak interactions within the proton. These effects are normally difficult to measure, but their intensity increases with the polarization of the particles, making them clearly visible.

Shortly before HERA’s time came to an end, the accelerator ran at a reduced proton energy for several months (460 and 575 GeV, instead of 920 GeV). Measurements at different energies, but under otherwise identical kinematic conditions, filter out the third structure function FL, which provides information on the behaviour of the gluons at small x. These measurements are without parallel and are particularly important for the understanding of QCD.

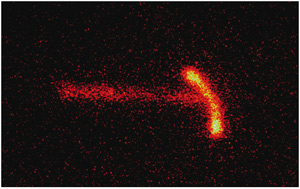

HERA provided another surprise soon after it went into operation. In events at the highest Q2, a quark is violently knocked out of the proton. In 10–15% of such cases, instead of breaking up into many new particles, the proton remains completely intact. This is about as surprising as if 15% of all head-on car crashes left no scratch on the cars. Such phenomena were familiar at low energies, and were generally described using the concepts of diffractive physics, which involve the pomeron, a hypothetical neutral particle with the quantum numbers of the vacuum. However, early HERA measurements showed that this concept did not hold up, failing completely in the hard diffraction range.

To conform with QCD, at least two gluons must be involved in a diffractive interaction to make it colour-neutral. Could hard diffraction therefore be related to the high gluon density at small x? The H1 and ZEUS results were clear: the colour-neutral exchange is indeed dominated by gluons. These observations at HERA led to the development of an entire industry devoted to describing hard diffraction, and the analyses and attempts at interpretation continue unabated. There have been some successes, but the results are not yet completely understood. It is therefore important to analyse the HERA data from all conceivable points of view to assess all theoretical interpretations appropriately.

The fundamental forces of nature

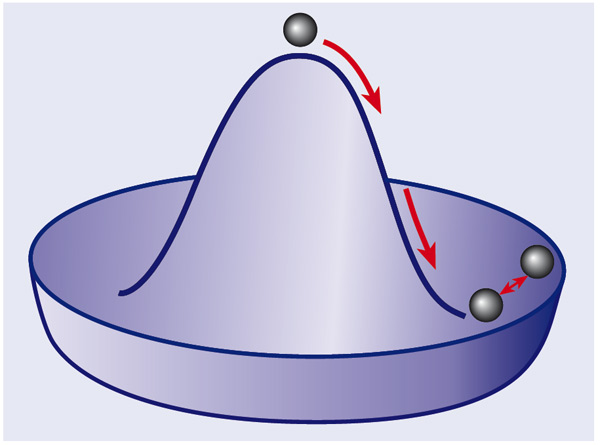

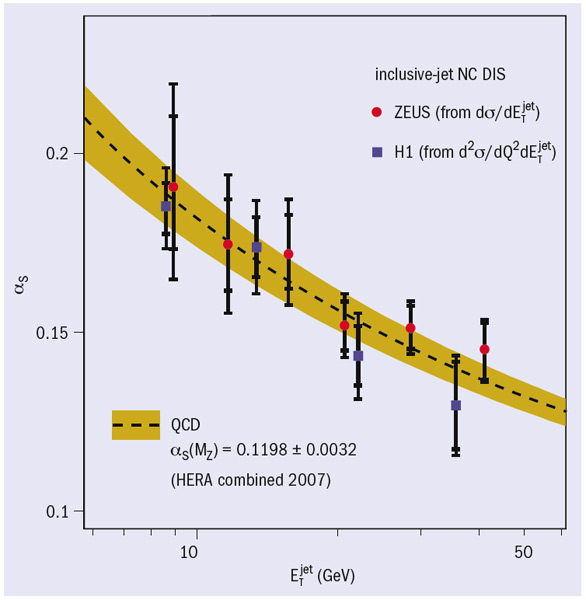

A special characteristic of the strong interaction is its unusual behaviour with respect to distance. While the electromagnetic interaction becomes weaker with increasing distance, the opposite is true for the strong force. It is only when the quarks are close together that the force between them is weak (asymptotic freedom); the force becomes stronger at greater distances, thus more or less confining the quarks within the proton. While other experiments have also determined the strong coupling constant αs as a function of energy, H1 and ZEUS for the first time demonstrated the characteristic running of αs over a broad range of energies in a single experiment (figure 3). Thus, the HERA results impressively confirmed the special behaviour of the strong force that David Gross, David Politzer and Frank Wilczek predicted 20 years ago – a prediction for which they won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2004.

Although the collaborations used HERA mostly for QCD studies, the aim of studying the electroweak interaction was part of the proposal for the machine. For instance, H1 and ZEUS measured the cross-sections of neutral and charged-current reactions as a function of Q2. At low-momentum transfers, i.e. large distances, the electromagnetic processes occur significantly more often than the weak ones because the electromagnetic force acts much more strongly than the weak force. At higher Q2, and thus smaller distances, both reactions occur at about the same rate, i.e. both forces are equally strong. H1 and ZEUS thus directly observed the effects of electroweak unification, which is the first step towards the grand unification of the forces of nature.

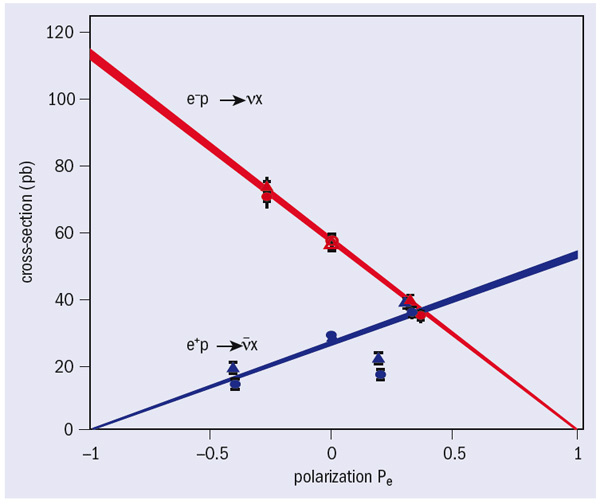

The longitudinal polarization of the electrons in HERA II also opened up new possibilities for studying the electroweak force. For example, theory predicts that because only left-handed neutrinos exist in nature, the transformation of a right-handed electron into a right-handed neutrino via the weak interaction should be impossible. H1 and ZEUS measured the charged currents as a function of the various polarization states, and proved that there are indeed no right-handed currents in nature, even at the high energies of HERA (figure 4).

Particle collisions at the highest Q2 are comparatively rare. Yet it is here, at the known limits of the Standard Model, that any new effects should appear. Thanks to the higher luminosity of HERA II, the collaborations can study this realm with enhanced precision. They have to date not observed any significant deviations from the Standard Model. The results from HERA substantially broaden the Standard Model’s range of validity and restrict the possible phase space for new phenomena, so refining the insights of the Standard Model all the way up to the highest momentum transfers.

The nucleon-spin puzzle

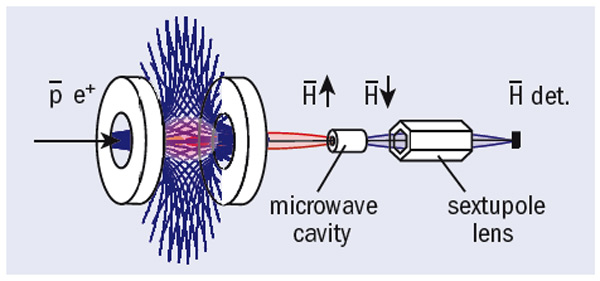

Another important contribution to our understanding of the proton is provided by another HERA experiment, HERMES, which was designed to study the origin of nucleon spin. In the mid-1980s, experiments at CERN and SLAC discovered that the three valence quarks account for only around a third of the total nucleon spin. Starting in 1995, the HERMES collaboration aimed to find out where the other two-thirds come from, by sending the longitudinally polarized electrons or positrons from HERA through a target cell filled with polarized gases.

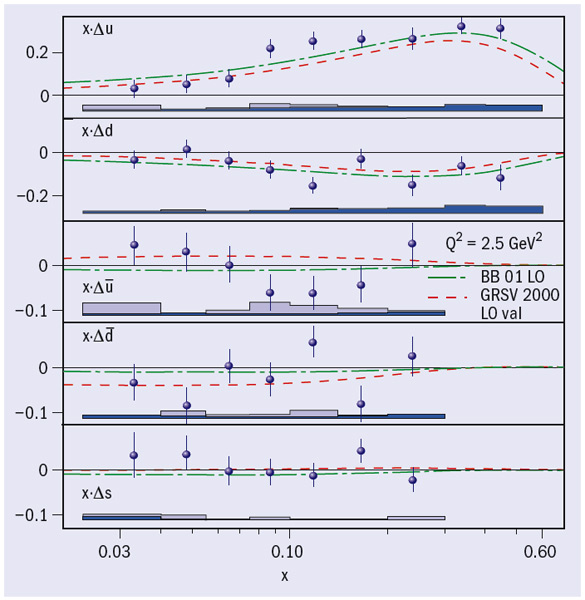

During HERA I, HERMES completed its first task, which was to determine the individual quark contributions to the nucleon spin. Using measurements on longitudinally polarized gases, the HERMES collaboration provided the world’s first model-independent determination of the separate contributions made to the nucleon spin by the up, down and strange quarks (figure 5). The results revealed that the largest contribution to the nucleon spin comes from the valence quarks, with the up quarks making a positive contribution, the down quarks a negative one. The polarizations of the sea quarks are all consistent with zero. The HERMES measurements therefore proved that the spin of the quarks generates less than half of the spin of the nucleon, and that the quark spins that do contribute come almost exclusively from the valence quarks – a decisive step toward the solution of the spin puzzle.

The HERMES team then turned its attention to gluon spin, making one of the first measurements to give a direct indication that the gluons make a small but positive contribution to the overall spin. The analysis of the latest data will yield more detailed information. Until recently, it was impossible to investigate the orbital angular momentum of the quarks experimentally. Now, using deeply virtual Compton scattering (DVCS) on a transversely polarized target, the HERMES team has made the first model-dependent extraction of the total orbital angular momentum of the up quarks. Analysis of the data taken with a new recoil detector in 2006–2007 will perfect the knowledge of DVCS and enable HERMES to make a key contribution to improving the models of generalized parton distributions, in the hope of soon identifying the total orbital angular momentum of the up quarks.

Parton distribution functions characterize the nucleon by describing how often the partons – quarks and gluons – will be found in a certain state. There are three fundamental quark distributions: the quark number density, which the H1 and ZEUS experiments have measured with high precision; the helicity distribution, which was the main result of measurements by HERMES with longitudinally polarized gases; and the transversity distribution, which describes the difference in the probabilities of finding quarks in a transversely polarized nucleon with their spin aligned to the nucleon spin, and quarks with their spin anti-aligned. Using data on transversely polarized hydrogen, the HERMES collaboration can now determine this transversity distribution for the first time. The measurements also provide access to the Sivers function, which describes the distribution of unpolarized quarks in a transversely polarized nucleon. As the Sivers function should vanish in the absence of quark orbital angular momentum, its measurement marks an additional important step in the study of orbital angular momentum in the nucleon. Analysis of the initial data shows that the Sivers function seems to be significantly positive, which indicates that the quarks in the nucleon do in fact possess a non-vanishing orbital angular momentum.

Although HERMES focuses on nucleon spin, the physics programme for the experiment extends much further, including, for example, studies of quark propagation in nuclear matter and quark fragmentation, tests of factorization and searches for pentaquark exotic baryon states. Analysis of the data collected up until the shutdown in June 2007 will provide unique insights here as well.

The LHC and beyond

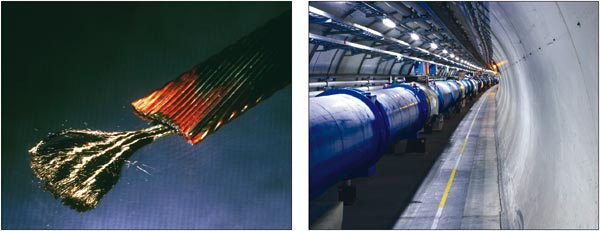

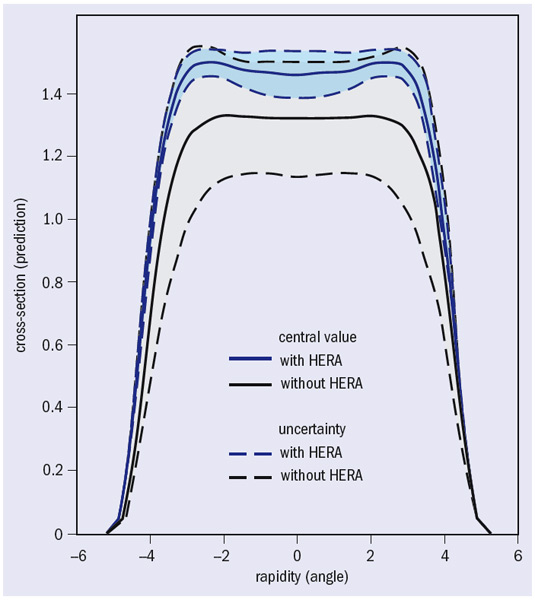

In 2008, the LHC will start colliding protons at centre-of-mass energies about 50 times higher than those at HERA. The results provided by HERA are essential for the interpretation of the LHC data: the proton–proton collisions at the LHC are difficult to describe, involving composite particles rather than point-like ones. It is therefore crucial to have the most exact understanding possible of the collisions’ initial state. This comes from HERA, for example, in the form of precise parton distribution functions of the up, down and strange quarks, and also the charm and bottom quarks (figure 6). An accurate knowledge of these distributions is vitally important, particularly for predictions of Higgs particle production at the LHC.

Many of these LHC-relevant measurements could only be carried out at HERA. To support the transfer of knowledge and create a long-term connection that takes account of the overlapping physics interest at HERA and the LHC, DESY and CERN have intensified their co-operation in this area. Many researchers from HERA, along with many students and PhD candidates, are already participating in the LHC experiments.

Over the past 15 years, HERA has enabled us to uncover a wealth of different – and partly unexpected – aspects of the proton and the fundamental forces. The analysis of the data recorded up until HERA’s closure in June 2007 is expected to last well into the next decade. The HERA collaborations will be melding these aspects into a vast and cohesive whole – a comprehensive description of strongly interacting matter at small distance scales and short time scales. Given HERA’s unique nature, this picture will endure for a long time and define for years, and possibly decades, our understanding of the dynamics of the strong interaction.

With their results, the HERA teams are now handing the baton over to the LHC collaborations, and also to the theorists. From the outset, the results from HERA have stimulated a large amount of theoretical work, particularly in the field of QCD, where an intensive and fruitful collaboration between theory and experiments has arisen. Thus, the knowledge of the proton and the fundamental forces gained from HERA forms the basis, not only for future experiments, but also for many current developments in theoretical particle physics – a rich legacy indeed.