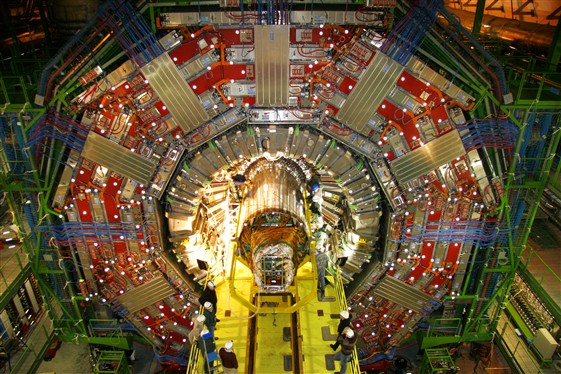

In December 1999 the CMS collaboration made the daring decision to change its tracking detector from a design that included gaseous detectors to one constructed entirely from silicon sensors, using both microstrip and pixel technology. On 15 December 2007, teams working in the cavern at Point 5 on the LHC installed the microstrip tracking system into the experiment. The pixel detector will soon follow, completing the CMS Tracker and marking the culmination of eight years of careful work to design, prototype, construct and commission the largest silicon detector ever built.

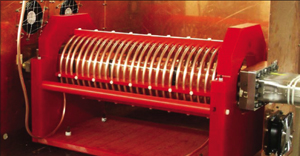

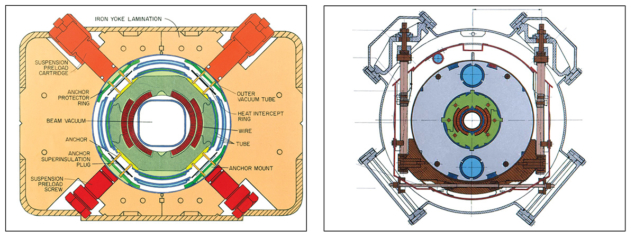

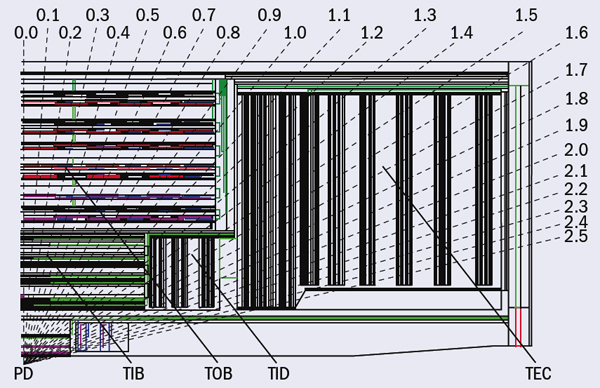

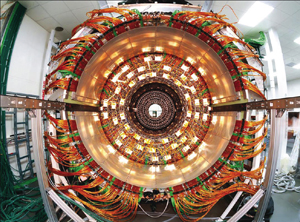

The collaboration envisaged a tracking system 40 times larger than any existing silicon detector system, with a performance comparable to the vertex detectors used at LEP. The detector would house about 205 m2 of silicon sensors (approximately the area of a tennis court) comprising 9.3 million microstrips and 66 million pixels. The aim was to achieve a precision of about 10 μm in spatial and vertex reconstruction resolutions – enough for excellent identification of heavy flavour hadrons – and excellent momentum measurement over a wide momentum range at the LHC. The readout would require 73,000 radiation-hard, low-noise microelectronics chips, almost 40,000 analogue optical links, 1000 power supply units and 500 off-detector readout and control modules. The complete system would be constructed in two halves from nine separate subdetector units: two each of microstrip inner barrels, outer barrels and endcaps, three pixel units in the form of a barrel system and two identical forward units.

In June 2000, the LHC Committee approved the Technical Design Report for the new design and the project formally got underway. A collaboration of more than 500 physicists and engineers from 51 institutions based in Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, the UK and the US, as well as from CERN, took joint responsibility for the project. They agreed that the inner barrel would be constructed by an Italian consortium, the outer barrel system by CERN together with Finnish and US groups, and the two endcaps by European teams. Swiss groups would build the central barrel region of the pixel system and a US collaboration would provide the forward pixel units.

The assembly project

The detailed design of each of the subdetector units took several years, including extensive testing of prototype sensors, modules and the readout, cooling and power systems. Production of the microstrip detector modules began in November 2004 using the sensors, hybrids and electronic components developed during the earlier phase – all of which had been thoroughly studied and evaluated to ensure maximum reliability and performance. Production of these modules was complete by March 2006. Then, after further substantial testing and thermal cycling, they were ready for mounting onto low-mass carbon fibre substructures with pre-assembled cooling circuits.

The project also became a massive worldwide logistical activity. The microstrip sensors were manufactured in Japan, with contributions from Italian industry, and shipped to Europe and the US for evaluation. The sensors were then moved to other European and US destinations for construction into modules using customized automated assembly equipment that CMS engineers had devised; and they journeyed further still for assembly into sub-units such as rods for the outer barrel, shells and discs for the inner barrel, and petals for the endcaps. The pixel system involved a similar transporting of parts, starting with commercially manufactured sensors from Norway.

The electronic readout system relied on developments in radiation-hard electronics and innovations in optical links, technologies that evolved rapidly in the 1990s. The CMS system culminated with the APV25 – the first large readout chip for a particle-physics experiment to use 0.25 μm CMOS integrated circuit technology – and novel analogue fibre-optic links. Much of this development was the responsibility of groups in the UK and teams at CERN, who worked closely with other CMS groups to assemble the elements of the readout system. CERN designed a set of control and ancillary chips using 0.25 μm CMOS technology, extensively exploited both in the Tracker and throughout CMS.

The collaboration also subcontracted a great deal of the assembly work to industries in several countries, including Austria, France, Italy, Japan, Switzerland and the UK

The automated assembly pioneered for this enormous system was vital for constructing thousands of modules quickly, so that the 15,200 required could be delivered on time. It also generated a huge interconnection requirement. Each module was assembled from one or two microstrip sensors, which had to be connected to the APV25 readout chip. The module chips also had to be bonded to their low-mass carrier. The intensive use of automatic-wire bonders met this demand and maintained consistent throughput with few delays, despite occasional variations in bond quality and rejection of sub-optimal modules.

The collaboration also subcontracted a great deal of the assembly work to industries in several countries, including Austria, France, Italy, Japan, Switzerland and the UK. In partnership with CMS institutes, the companies manufactured components and produced electronics boards, mounting and aligning semiconductor lasers, optical fibres, photodiodes, and analogue and digital electronics, including field-programmable gate arrays that were then state of the art. All modules were thoroughly tested in industry – often using CMS-constructed test equipment – then re-tested for acceptance in CMS laboratories. It is impossible here to do justice to the efforts of the CMS institutes, all of which took on significant tasks in assembly, evaluation and procurement.

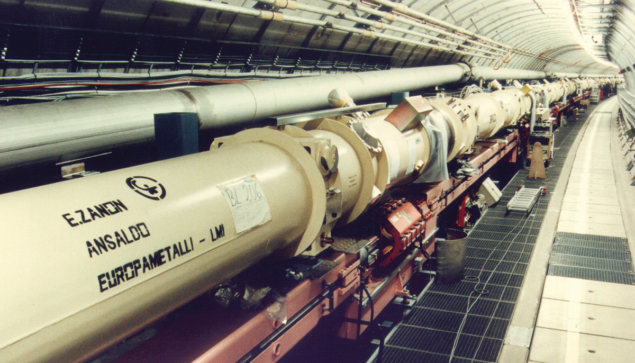

Collaboration members constructed new facilities in many institutions for assembling the subdetectors, as well as expanding and utilizing large laboratories such as at CERN, Fermilab and Pisa. Aachen assembled one of the Tracker endcaps, while Florence, Pisa and Torino jointly integrated the inner barrels and discs. There were intensive reviews at all system levels for each stage of production and integration to ensure that quality and performance were maintained.

On the main CERN site, CMS built a facility to assemble the final detector and to provide an environment where a substantial fraction of it could be fully commissioned before final installation into CMS at Point 5. The Tracker Integration Facility is a 350 m2 class 100,000 cleanroom, which was also used to integrate the entire outer-barrel system and the second endcap. Each subdetector underwent testing and thermal cycling before transportation to CERN. Further acceptance tests took place after arrival before final integration into the support structure.

The two halves of the outer barrel were built inside the Tracker support tube, which is a low-mass carbon fibre cylinder 5.4 m long and 2.5 m in diameter. The outer-barrel subdetector was completed in November 2006. The inner-barrel halves arrived at CERN in April and September 2006 for final testing before insertion into the outer barrel. The first half section was placed in position in December 2006 and the second half inner barrel and the endcap followed rapidly, with integration of the second endcap completed on 22 March 2007.

As each subdetector was assembled, the teams re-tested it to ensure that it continued to achieve the required performance. The integration facility included rack-mounted electronics, cooling and air-conditioning, which allowed the Tracker to observe cosmic-ray events before installation underground. This incorporated a quarter of the complete safety, control, power, data-acquisition and computing systems for the Tracker – destined eventually for the CMS caverns – including electrical and optical cables, which were to be re-used to keep down costs.

From March until August 2007, all aspects of the Tracker underwent testing, including safety, control and monitoring systems.Several million cosmic-ray events were recorded at five operating temperatures ranging between –15 °C and +15 °C. The data were reconstructed using the CMS-distributed computing Grid and were analysed throughout the world. All systems operated reliably during this five-month period and the collaboration verified that the assembled detector met the performance specifications.

Analysis of the cosmic-ray data shows that the performance of the microstrip tracker is excellent. The number of inactive strips is below one part in 2000; noisy strips do not exceed 0.5%. The signal-to-noise ratio, which depends on sensor thickness, was about 28 for 300 μm sensors. Measurements showed the track cluster finding efficiency to be better than 99.8%. All of these results meet or exceed expectations, which bodes well for LHC physics.

Final installation

At the CMS experimental area at Point 5, preparation for installing the Tracker began before the solenoid magnet was even lowered into the cavern in February 2007. Installation and testing of the cooling plants, power systems and off-detector readout electronics, as well as control and data-acquisition systems took place throughout 2007.

The final performance of the subdetectors in LHC collisions is crucially dependent on the electrical quality of the underground environment, which will only become fully understood after the experiment is complete. The Tracker’s electronics are exquisitely sensitive to tiny signals and must be protected against unwanted noise. To achieve this, 32 interconnection units (patch panels) serving different sectors of the Tracker were installed at the edge of the CMS solenoid, through which all electrical power and cooling services – as well as optical fibres and monitoring wires – pass. The patch panels filter electronic noise and will permit in situ optimization of the detector’s grounding. They also provide termination for cooling, optical links and electrical cables so that all services could be tested as far as possible in CMS before the Tracker arrived.

By late September 2007, the installation teams had completed the massive task of installing cooling systems for 450 loops, 2300 power and 400 fibre-optic cables. The microstrip tracker was transported overnight to Point 5 on 12 December and installation into CMS was completed over the following two days. Connection of the services from the patch panels to the Tracker, and commissioning the Tracker with the rest of CMS, will be completed this spring.

The pixel system

Although a physically smaller device, the pixel system has about a factor of seven more channels. Being at the centre of the detector, concern about minimum material budget and higher radiation levels necessitates even greater attention. Interconnection technologies – especially fine-pitch bump bonding, which were not yet mature for applications in particle physics – had to be studied and, in some cases, developed in CMS labs to allow construction of the detector. The pixel assembly project followed a similar course to the microstrip tracker, with significant transport of parts around the world. Fermilab was at the centre of US activity, and was where the final assembly of the forward system was completed following plaquette construction at Purdue University. The team at the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) assembled the barrel subdetector with the collaboration of Swiss universities. PSI also designed the pixel readout chip, while other chips were developed in PSI and the US; the pixel detectors have also exploited components from the microstrip tracker.

The pixel system is scheduled for insertion into CMS following the installation and bake out of the LHC beam pipe in April. The complete forward subdetector was transported to CERN from Fermi-lab in December 2007 and is now undergoing extensive system tests at the Tracker Integration Facility. The barrel subdetector is also complete and currently being commissioned at PSI. It will be transported to CERN in April.