Accelerator physicists at Brookhaven National Laboratory have developed a way to apply the technique of stochastic cooling to the beams in the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC). This is the first time that the technique for concentrating a particle beam has been used in a machine where the particles are bunched. The results of the tests in 2007, which offer a “fast track” to upgrading the luminosity at RHIC, were presented in February at the Quark Matter 2008 meeting in Jaipur.

RHIC circulates two beams of heavy ions moving in opposite directions in two separate rings, each beam being in bunches of more than 109 ions per bunch. With the high electrical charges of the heavy ions, the particles spread out (“heat up”) while the beams are stored during colliding-beam operations, and ultimately they become lost. This reduces the collider’s luminosity and, in consequence, the probability for collisions. It also necessitates beam “cleaning” to avoid particles diverging into the superconducting magnets and causing them to quench.

One way to overcome this effect is to direct the particles back on track, which is just what happens with stochastic cooling. Invented by Simon van der Meer at CERN, the technique was applied in the 1980s to accumulate and cool antiprotons prior to injection and acceleration in the SPS. This led to the Nobel Prize for Physics for van der Meer and Carlo Rubbia, when the W and Z particles were discovered in proton–antiproton collisions in the SPS. However, later tests at both the SPS and Fermilab’s Tevatron showed that there are complications when applying stochastic cooling to a machine where the particles are already in a bunched beam.

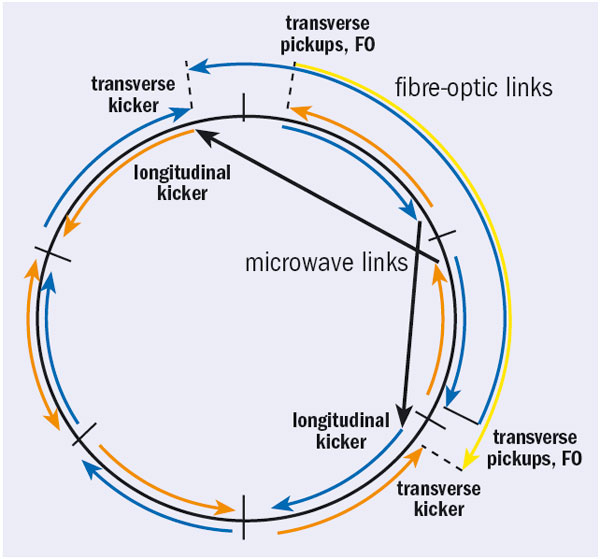

The technique relies on measuring the random fluctuations in the beam shape and size – hence the name “stochastic”, which is derived from statistics and means random. The measurements are made at one point on the accelerator by devices that generate signals proportional to how far the particles are straying from their ideal positions.

At RHIC these devices send the signals via fibre-optic or microwave links to a position ahead of the speeding beam, where electric fields are generated to kick the charged particles back towards their ideal positions. This results in more tightly squeezed (“cooler”) ion bunches. The signals stay ahead of the beam by taking one of two shortcuts: either travelling from one point to another across the circular accelerator or backtracking along the circle to meet the speeding beam roughly halfway round on its next pass.

So far, the team at RHIC has tested stochastic cooling in the longitudinal direction – along the direction of the beam – in one of RHIC’s two rings. Longitudinal cooling compensates for the ion bunches’ tendency to lengthen as they circulate. This improvement has already increased RHIC’s heavy-ion collision rate by 20%. The team has now installed equipment to implement the longitudinal cooling system in the second of RHIC’s rings.

The aim is also to install a system for transverse cooling in one of the beams before 2009. This would allow tests of significantly increased luminosity in gold–gold collisions in RHIC.

This successful demonstration of stochastic cooling provides an alternative way to increase collision rates that is less costly and quicker than other methods considered for RHIC II, electron cooling in particular, which would cost $95 m. Simulations suggest that stochastic cooling, together with other improvements, could increase the luminosity for gold–gold collisions to some 50 × 1026 cm–2s–1, or about 70% of the design goal for RHIC II. The team should be able to complete the system for stochastic cooling with an extra $7 m. According to Steven Vigdor, Brookhaven Associate Laboratory director for nuclear and particle physics, the laboratory hopes to implement the full stochastic cooling system by 2011.