By Laurence Plévert

World Scientific

Paperback: £32

E-book: £41

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes obtient le prix Nobel de physique en 1991 « pour avoir découvert que les méthodes développées dans l’étude des phénomènes d’ordre s’appliquant aux systèmes simples peuvent se généraliser à des formes plus complexes, cristaux liquides et polymères ». Ni invention ni découverte, c’est un curieux intitulé. Le comité semble honorer un homme plus qu’une contribution identifiée. De fait, la vie de de Gennes se lit comme une épopée. Il naît en 1932 d’une famille alliant la banque et l’aristocratie. Ses parents se séparent, il est doublement choyé. La guerre éclate, c’est l’occasion de vacances alpestres. Cette enfance hors du commun lui apprend discipline et curiosité et lui donne une grande confiance en lui.

Attiré par les sciences à 15 ans, il surmonte les années difficiles de la classe préparatoire en jouant dans un orchestre de jazz. Reçu premier à l’Ecole normale supérieure, il commence la vie libre de normalien, se mariant et devenant papa avant l’agrégation. Il se passionne pour la mécanique quantique et la théorie des groupes, qu’il décortique dans les livres. Feynman est son modèle. L’intuition doit rester souveraine, et il l’applique aussi en politique où il rejette les modes de l’époque. Il vit une révélation avec l’école d’été des Houches, où il rencontre Pauli, Peierls… Les deux mois les plus importants de sa vie, dit-il. Sa vocation pour la physique s’y confirmera, mais quelle voie suivre ? La physique nucléaire ? « J’ai l’impression que personne ne sait décrire une interaction sinon en ajoutant des paramètres de manière ad hoc ».

Sorti de l’ENS, il intègre la division théorique de Saclay. Après son service militaire, il devient professeur à Orsay à l’âge de 29 ans. On lui laisse carte blanche, il s’attaque à la supraconductivité, montant un laboratoire à partir de rien. Se laissant guider par l’imagination, il mélange expérience et théorie. Aux plus jeunes, il insuffle l’enthousiasme, son charisme opère sur tous.

Il quitte Orsay en 1971, appelé au prestigieux Collège de France, pour y créer son propre laboratoire. Il y développe la science de « la matière molle », comprenant les bulles et les sables, les gels, les polymères… Théoricien du pratique, il prône une forte collaboration avec l’industrie. Pluridisciplinaire avant la lettre, il exploite les analogies suggérées par sa grande culture scientifique.

Dans son parcours sans faute, une hésitation apparaît. « Au milieu du chemin de sa vie », il sent le défi de l’âge. Il le relève allègrement fondant une seconde famille, en maintenant un bon rapport avec la première où vivent trois grands enfants. Sa femme ne s’insurge pas. Sa vie privée est aussi fertile que sa carrière, et trois nouveaux enfants naîtront.

Arrive l’heure des distinctions. Il est élu à l’Académie des Sciences, il reçoit la médaille d’or du CNRS, la Légion d’honneur, on lui propose un ministère. Tout en demeurant au Collège de France, il est appelé à la direction de l’ESPCI, qu’il remodèle à son goût, il s’y fait une réputation de despote. C’est un grand patron qui assume sa fonction. De fait, son autorité naturelle suscite chez ses collaborateurs une crainte sacrée. L’apothéose que représente le prix Nobel lui permet d’appliquer ses idées avec encore moins de retenue. Grand communicateur, il popularise ses idées à la télévision.

Un cancer se déclare, il s’accroche à ses activités. Retraité du Collège de France, il poursuit sa vie de recherche à l’Institut Curie dans le domaine des neurosciences. Il meurt en 2007 après une dure bataille.

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes fut un homme de convictions. Parfois décrié pour ses prises de position, il ne craint pas de secouer les habitudes en s’attaquant aux structures sclérosées : « L’université a besoin d’une révolution. » Autre cheval de bataille : la « Big Science » ; il s’oppose au laboratoire de rayonnement synchrotron Soleil et au projet ITER. Humaniste, il publie un délicieux tableau de caractères à la manière de la Bruyère, et il avoue : « J’ai tendance à croire que notre esprit a des besoins autant rationnels qu’irrationnels. »

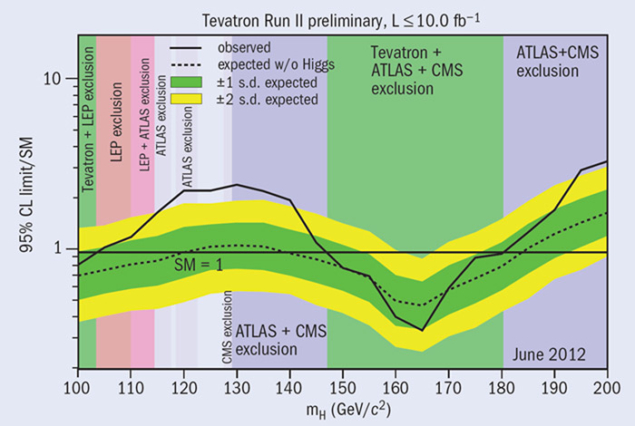

Bouillonnant d’idées, auteur de 550 publications, homme d’influence qui s’exprime de manière franche, il ose dire : « Il faut accélérer la mort lente de champs épuisés comme la physique nucléaire », et il remarque : « Quand j’ouvrais PRL en 1960, je trouvais chaque fois une idée révolutionnaire, aujourd’hui j’arrive à 2 ou 3 idées par an, dans un journal devenu 5 fois plus épais. » Il est vrai que les idées neuves se font rares. Nous vivons sur l’acquis d’anciennes avancées théoriques, et le Higgs découvert récemment a été postulé il y a 50 ans. D’où le le sentiment dérangeant que le progrès avance plus laborieusement.

Pierre-Gilles de Gennes fut un esprit fertile et passionné, mais il vécut aussi dans une période favorable, offrant des domaines vierges permettant de multiplier les recherches. Une carrière comme la sienne semble impossible aujourd’hui, les spécialités poussées à l’extrême étouffant les initiatives individuelles.

La biographie, très bien écrite par la journaliste Laurence Plévert, est truffée d’anecdotes, elle se lit comme un roman qui emplit le lecteur d’un optimisme renouvelé sur les potentialités de l’aventure humaine et de la recherche fondamentale.

« Renaissance man », dit la quatrième de couverture ; j’oserai comparer Pierre-Gilles de Gennes à un monarque éclairé façon condottiere, ce qui ne contredit pas l’aphorisme d’un journaliste résumant l’attrait de l’homme : « Il est quelqu’un qu’on aimerait avoir comme ami, pour partager le privilège de se sentir un instant plus intelligent. »

This book is a translation of the original French edition Pierre-Gilles de Gennes. Gentleman physicien (Belin, 2009).