The LHC is a tremendously powerful tool built to explore physics at the tera-electron-volt scale. This year it is being operated with a centre-of-mass energy of 8 TeV, which is a little over half of the full design energy. This beats by a factor of four the previous world record held by Fermilab’s Tevatron, which shut down a year ago. For the study of ultrahigh-energy collisions, a second figure of merit of the machine – luminosity – is also of crucial importance. Here, the LHC is living up to its promise. In the first eight months of proton–proton operations in 2012, the ATLAS and CMS experiments have registered close to 10 fb–1 at 8 TeV, a data set similar to that collected during the entire 10-year Run II at the Tevatron.

In this uncharted territory at the energy frontier, known particles behave in unfamiliar ways. For the first time, the heaviest known particles – the W and Z bosons, the top quark and the recently discovered new boson – do not seem quite so heavy. Their rest masses (of the order 100 GeV) are small compared with the energy unleashed in the most energetic collisions, which can be up to several tera-electron-volts. Therefore, every so often these massive particles are produced with an enormous surplus of kinetic energy such that they fly through the laboratory at enormous speed.

A serious challenge

The velocity of these massive particles has implications for the way that they are observed in experiments. For particles produced with a large boost, the decay products (leptons or jets of hadrons) are emitted at small angles to the original direction of their parent. The full energy of the massive particle is deposited in a tiny area of the detector. Reconstructing and selecting these highly collimated topologies represents a serious challenge. For a sufficiently large boost, the two jets of particles that appear in hadronic two-body decays (W, Z, H → qq) cannot be resolved by standard reconstruction algorithms.

An approach pioneered by Michael Seymour, now at Manchester University, provides an interesting alternative by simply turning the problem round (Seymour 1994). Instead of trying to resolve two jets and adding up their momenta to reconstruct the parent particle, the technique is to reconstruct a single jet that contains the full energy of the decay. The fat jet containing the decay of a boosted object must then be distinguished from ordinary jets that are produced by the million at the LHC. This is achieved through an analysis of the jet’s internal structure. This alternative appears to be the most promising approach whenever the energy of the massive particle exceeds its rest mass by a factor of three or more. The boosted regime thus starts at an energy a little over 200 GeV for a W boson and at roughly 500 GeV for a top quark.

Dawn of the boosted era

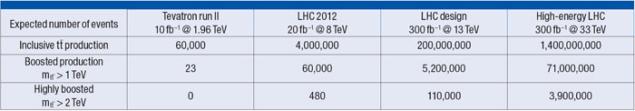

The LHC is the first machine where boosted objects are a crucial part of the physics programme. A more quantitative grasp of exactly how the LHC crosses the threshold of the boosted regime is obtained by comparing the expectation in the Standard Model for the production rate of top quarks – the heaviest known particle – at past, present and future colliders.

Since the discovery of the top quark in 1995, the Tevatron has produced tens of thousands of these particles. A large majority of these were produced approximately at rest; only two dozen or so top quark pairs had a mass exceeding 1 TeV. By contrast, the LHC is a real top factory. In 2012 alone, it has already produced more than 20 times as many top-quark pairs as the Tevatron had in its lifetime. At the LHC, most top-quark pairs are still produced close to threshold but production in the boosted regime increases by several orders of magnitude. Several tens of thousands of top-quark pairs will be produced this year with mtt > 1 TeV.

Impressive as these numbers may be, these first years mark just the start of a long programme. After a shutdown in 2013–2014, the LHC should emerge in its full glory, with protons colliding close to the design energy of 14 TeV and the experiments collecting tens of inverse femtobarns of data each year. Boosted top quarks will be produced by the millions in the next phase of the LHC and a sizeable sample of top quarks with tera-electron-volt energies is expected.

Over the past few years, much work has been done to address the experimental challenges inherent in the new approach for boosted objects. Using the substructure of jets requires a precise understanding of how they are formed. Sophisticated new algorithms to identify boosted objects – W-taggers, top-taggers, Higgs-taggers – have been put forward and developed further by the LHC experiments.

The potential of these new methods to improve the sensitivity of LHC analyses has been estimated by using Monte Carlo simulations. One obvious area where tools tailored to boosted topologies might make a difference is in searches for signals of physics beyond the Standard Model in the most energetic collisions. Several such cases have been studied in detail. A significant pay-off in physics return is expected in resonance searches in the tt mass spectrum and studies of diboson production at high energy. Boosted techniques may also be applied to the high-energy tails of continuum production in the Standard Model. In what has become a seminal paper, the seemingly hopeless Higgs search in the WH, H → bb channel was resurrected by requiring that the Higgs boson is produced with moderate boost (Butterworth et al. 2008).

BOOST2012

By bringing together key theorists and experimentalists every year, a series of workshops known as BOOST offers a forum for discussion of the progress in this fast-moving field. The first of these at SLAC (2009) and in Oxford (2010) focused on Monte Carlo studies that laid the foundations for what was to come. At Princeton in 2011, the first measurements on LHC data of jet substructure were shown, as well as candidate events for the world’s first boosted top quarks. The display of one of these was chosen as the logo for the latest workshop, BOOST2012, organized by the Instituto de Física Corpuscular (IFIC) in Valencia. Held near the Mediterranean in late July – soon after the historic announcement at CERN of the discovery of a Higgs-like boson – this latest workshop definitely held the promise of becoming the “hottest” BOOST event so far. The 80 or so participants definitely did not let the organizers down.

A lively debate arose in the session centred on attempts to predict the invariant mass of energetic jets

A lively debate arose in the session centred on attempts to predict the invariant mass of energetic jets, comparing them with the more sophisticated measurements that have become available this year. Experimentalists and theorists joined efforts to develop new techniques to deal with the impact of the 30 overlapping collisions that occur every time that the LHC bunches cross. The recent discovery at CERN fuelled the discussion on the potential of these techniques to help isolate a Higgs signal in the crucial bb decay channel. However, perhaps the most exciting results were presented in the session on applications of these new ideas to searches for new physics with top quarks at the LHC.

Speakers from the ATLAS and CMS collaborations reviewed their experiments’ searches for top-quark pair production through processes not present in the Standard Model. Some of these use the classical scheme to reconstruct top quarks, where the hadronic top-quark decay (t → Wb → b qq)) is reconstructed by looking for three jets and then combining their four-vectors. Other searches adopt the “boosted” approach and reconstruct highly boosted top quarks as a single jet. While all searches have yielded negative results – reconstructed tt mass spectra following the Standard Model template to a frustrating precision – an evaluation of their relative sensitivity yields an encouraging conclusion. In both experiments, searches employing novel techniques specifically designed for boosted top-quark decay topologies are found to be considerably more sensitive than their classical counterparts in the high-mass region. This was expected from Monte Carlo studies, but these analyses show that the systematic uncertainties in the description of jet substructure, as well as the impact of pile-up on the experiments’ performance, are under control. In that sense, seeing these excellent results so early in the LHC programme constitutes a real proof of principle for this new approach.

The LHC produces – for the first time in the laboratory – large numbers of highly boosted heavy Standard Model particles. Results presented at BOOST2012 show that the development of new tools is on track to extract the maximum knowledge from the most energetic collisions. After careful commissioning and with conservative estimates of the uncertainties that affect this new approach, the first analyses employing boosted techniques to search for tt resonances clearly outperform their classical counterparts. These results are a milestone for the people in the field. The boosted paradigm is clearly ready to take on a major role in the LHC physics programme.

• The author would like to thank Gavin Salam for his useful comments in the preparation of this document