A noble gas, a missing scientist and an underground laboratory. It could be the starting point for a classic detective story. But a love story? It seems unlikely. However, add in a back-story set in Spain during General Franco’s rule, plus a “eureka” moment in California, and the ingredients are there for a real romance – all of it rooted firmly in physics.

Image credit: Jorge Quiñoa & Jot Down.

When Spanish particle-physicist Juan José Gómez Cadenas arrived at CERN as a summer student, the passion that he already had for physics turned into an infatuation. Thirty years later and back in his home country, Gómez Cadenas is pursuing one of nature’s most elusive particles, the neutrino, by looking where it is expected not to appear at all – in neutrinoless double-beta decay. Moreover, fiction has become entwined with fact, as he was recently invited to write a novel set at CERN. The result, Materia Extraña (Strange matter), is a scientific thriller that has already been translated into Italian.

Critical point

“Particle physicists were a rare commodity in Spain when the country first joined CERN in 1961,” Cecilia Jarlskog noted 10 years ago after a visit to “a young and rapidly expanding community” of Spanish particle physicists. Indeed, the country left CERN in 1969, when Juan was only nine years old and Spain was still under the Franco regime. Young Juan – or “JJ” as he later became known – initially wanted to become a naval officer, like his father, but in 1975 he was introduced to the wonders of physics by his cousin; Bernardo Llanas had just completed his studies with the Junta de Energía Nuclear (the forerunner of CIEMAT, the Spanish research centre for energy, the environment and technology) at the same time as Juan Antonio Rubio, who was to do so much to re-establish particle physics in Spain. The young JJ set his sights on the subject – “Suddenly the world became magic,” he recalls, “I was lost to physics” – and so began the love affair that was to take him to CERN and, in a strange twist, to write his first novel.

The critical point came in 1983. JJ was one of the first Spanish students to gain a place in CERN’s summer student programme when his country rejoined the organization. It was an amazing time to be at the laboratory: the W and Z bosons had just been discovered and the place was buzzing. “I couldn’t believe this place, it was the beginning of an absolute infatuation,” he says. That summer he met two people who were to influence his career: “My supervisor, Peter Sonderegger, with whom I learnt the ropes as an experimental physicist, and Luis Álvarez-Gaume, a rising star who took pity on the poor, hungry fellow-Spaniard hanging around at night in the CERN canteen.” After graduating from Valencia University, JJ’s PhD studies took him to the DELPHI experiment at CERN’s Large Electron–Positron collider. With the aid of a Fulbright scholarship, he then set off for America to work on the Mark II experiment at SLAC. From there it was back to CERN and DELPHI again, but in 1994 he left once more for the US, this time following his wife, Pilar Hernandez, to Harvard. An accomplished particle-physics theorist, she converted her husband to her speciality, neutrino physics, thus setting him on the trail that would lead him through the NOMAD, HARP and K2K experiments to the challenge of neutrinoless double-beta decay.

The neutrinoless challenge

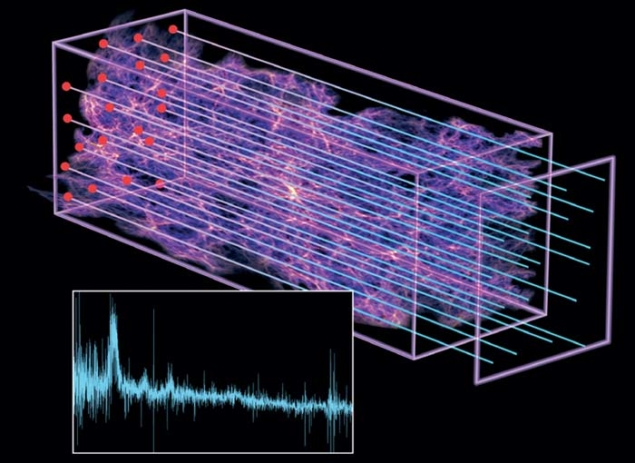

Established for 15 years as professor of physics at the Institute of Nuclear and Particle Physics (IFIC), a joint venture between the University of Valencia and the Spanish research council (CSIC), he is currently leading NEXT – the Neutrino Experiment with a Xenon TPC. The aim is to search for neutrinoless double-beta decay using a high-pressure xenon time-projection chamber (TPC) in the Canfranc Underground Laboratory in the Spanish Pyrenees. JJ believes that the experiment has several advantages in the hunt for this decay mode, which would demonstrate that the neutrino must be its own antiparticle, as first proposed by Ettore Majorana (whose own life ended shrouded in mystery). The experiment uses xenon, which is relatively cheap and also cheap to enrich because it is a nobel gas. Moreover, NEXT uses gaseous xenon, which gives 10 times better energy resolution for the decay electrons than the liquid form. By using a TPC, it also provides a topological signature for the double-beta decay.

The big challenge was to find a way to amplify the charge in the xenon gas without inducing sparks. The solution came when JJ talked to David Nygren, inventor of the TPC at Berkeley. “It was one of those eureka moments,” he recalls. “Nygren proposed using electroluminescence, where you detect light emitted by ionization in a strong field near the anode. You can get 1000 UV photons for each electron. He immediately realized that we could get the resolution that way.” JJ then came up with an innovative scheme to detect those electrons in the tracking plane using light-detecting pixels (the silicon photomultiplier) – and the idea for NEXT was born. “It is hard for me not to believe in the goddess of physics,” says JJ. “Every time that I need help, she sends me an angel. It was Abe Seiden in California, Gary Feldman in Boston, Luigi di Lella and Ormundur Runolfson at CERN, Juan Antonio Rubio in Spain … and then Dave. Without him, I doubt NEXT would have ever materialized.” The collaboration now involves not only Spain and the US but also Colombia, Portugal and Russia. The generous help of a special Spanish funding programme, called CONSOLIDER-INGENIO, provided the necessary funds to get it going. “More angels came to help here,” he explains, “all of them theorists: José Manuel Labastida, at the time at the ministry of science, Álvaro de Rújula, my close friend Concepción González-García … really, the goddess gave us a good hand there.”

Despite the financial problems in Spain, JJ says that “there is a lot of good will” in MINECO, the Ministry of Economy, which currently handles science in Spain. He points out that there has already been a big investment in the experiment and that there is full support from the Canfranc Laboratory. He is particularly grateful for the “huge support and experience” of Alessandro Bettini, the former director of the Gran Sasso National Laboratory in Italy, who is now in charge at Canfranc. JJ finds Bettini and Nygren – both in their mid-seventies – inspirational characters, calling them the “Bob Dylans” of particle physics. Indeed, he set up an interview with both of them for the online cultural magazine, Jotdown – where he regularly contributes with a blog called “Faster than light”.

In many ways, JJ’s trajectory through particle physics is similar to that of any talented, energetic particle physicist pursuing his passion. So what about the novel? When did an interest in writing begin? JJ says that it goes back to when his family eventually settled in the town of Sagunto, near Valencia, when he was 15. An ancient city where modern steel-making stands alongside Roman ruins, he found it “a crucible of ideas”, where writers and artists mingled with the steel-workers, who wanted a more intellectual lifestyle for their children – especially after the return of democracy with the new constitution in 1978, following Franco’s death. JJ started writing poetry while studying physics in Sagunto, and when physics took him to SLAC in 1986, as a member of Stanford University, he was allowed to sit in on the creative-writing workshop. “I was not only the only non-native American but also the only physicist,” he recalls. “I’m not sure that they knew what to make of me.” Years later, he continued his formal education as a writer at the prestigious Escuela de Letras in Madrid.

A novel look at CERN

Around 2003, CERN was starting to become bigger news, with the construction of the LHC, experiments on antimatter and an appearance in Dan Brown’s mystery-thriller Angels & Demons. Having already written a book of short stories, La agonía de las libélulas (Agony of the dragonflies), published in 2000, JJ was approached by the Spanish publisher Espasa to write a novel that would involve CERN. Of course, the story would require action but it would also be a personal story, imbued with JJ’s love for the place. Materia Extraña, published in 2008, “deals with how someone from outside tries to come to grips with CERN,” he explains, “and also with the way that you do science.” It gives little away to say that at one and the same time it is CERN – but not CERN. For example, the director-general is a woman, with an amalgam of the characteristics that he observes to be necessary for women to succeed in physics. “The novel was presented in Madrid by Rubio,” says JJ. “At the time, we couldn’t guess he had not much time left.” (Rubio was to pass away in 2010.)

When asked by Espasa to write another book, JJ turned from fiction to fact and the issue of energy. Here he encountered “a kind of Taliban of environmentalism” and became determined to argue a more rational case. The result was El ecologista nuclear (The Nuclear Environmentalist, now published in English) in which he sets down the issues surrounding the various sources of energy. Comparing renewables, fossil fuels and nuclear power, he puts forward the case for an approach based on diversity and a mixture of sources. “The book created a lot of interest in intellectual circles in Spain,” he says. “For example, Carlos Martínez, who was president of CSIC and then secretary of state (second to the minister) liked it quite a bit. Cayetano López, now director of CIEMAT, and an authority in the field, was kind enough to present it in Madrid. It has made some impact in trying to put nuclear energy into perspective.”

So how does JJ manage to do all of this while also developing and promoting the NEXT experiment? “The trick is to find time,” he reveals. ‘We have no TV and I take no lunch, although I go for a swim.” He is also one of those lucky people who can manage with little sleep. “I write generally between 11 p.m. and 2 a.m.,” he explains, “but it is not like a mill. I’m very explosive and sometimes I go at it for 12 hours, non-stop.”

He is now considering writing about nuclear energy, along the lines of the widely acclaimed Sustainable Energy – without the hot air by Cambridge University physicist David MacKay, who is currently the chief scientific adviser at the UK’s Department of Energy and Climate Change. “The idea would be to give the facts without the polemic,” says JJ, “to really step back.” He has also been asked to write another novel, this time aimed at young adults, a group where publisher Espasa is finding new readers. While his son is only eight years old, his daughter is 12 and approaching this age group. This means that he is in touch with young-adult literature, although he finds that at present “there are too many vampires” and admits that he will be “trying to do better”. That he is a great admirer of the writing of Philip Pullman, the author of the bestselling trilogy for young people, His Dark Materials, can only bode well.

• For more about the NEXT experiment see the recent CERN Colloquium by JJ Gómez Cadenas at http://indico.cern.ch/conferenceDisplay.py?confId=225995. For a review of El ecologista nuclear see the Bookshelf section of this issue.