Image credit: DESY.

The LHC at CERN is a prime example of worldwide collaboration to build a large instrument and pursue frontier science. The discovery there of a particle consistent with the long-sought Higgs boson points to future directions both for the LHC and more broadly for particle physics. Now, the international community is considering machines to complement the LHC and further advance particle physics, including the favoured option: an electron–positron linear collider (LC). Two major global efforts are underway: the International Linear Collider (ILC), which is distributed among many laboratories; and the Compact Linear Collider (CLIC), centred at CERN. Both would collide electrons and positrons at tera-electron-volt energies but have different technologies, energy ranges and timescales. Now, the two efforts are coming closer together and forming a worldwide linear-collider community in the areas of accelerators, detectors and resources.

Last year, the organizers of the 2012 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium held in Anaheim, California, decided to arrange a Special Linear Collider Event to summarize the accelerator and detector concepts for the ILC and CLIC. Held on 29–30 October, the event also included presentations on the impact of LC technologies for different applications and a discussion forum on LC perspectives. It brought together academic, industry and laboratory-based experts, providing an opportunity to discuss LC progress with the accelerator and instrumentation community at large, and to justify the investments in technology required for future particle accelerators and detectors. Representatives of the US Funding Agencies were also invited to attend.

The CLIC studies focus on an option for a multi-tera-electron-volt machine using a novel two-beam acceleration scheme

CERN’s director-general, Rolf Heuer, introduced the event before Steinar Stapnes, CLIC project leader, and Barry Barish, director of the ILC’s Global Design Effort (GDE), reviewed the two projects. The ILC concept is based on superconducting radio-frequency (SRF) cavities, with a nominal accelerating field of 31.5 MV/m, to provide e+e– collisions at sub-tera-electron-volt energies in the centre-of-mass. The CLIC studies focus on an option for a multi-tera-electron-volt machine using a novel two-beam acceleration scheme, with normal-conducting accelerating structures operating at fields as high as 100 MV/m. In this approach, two beams run parallel to each other: the main beam, to be accelerated; and a drive beam, to provide the RF power for the accelerating structures.

Both studies have reached important milestones. The CLIC Conceptual Design Report was released in 2012, with three volumes for physics, detectors and accelerators. The project’s goals for the coming years are well defined, the key challenges being related to system specifications and performance studies for accelerator parts and detectors, technology developments with industry and implementation studies. The aim is to present an implementation plan by 2016, when LHC results at full design energy should become available.

The ILC GDE took a major step towards the final technical design when a draft of the four-volume Technical Design Report (TDR) was presented to the ILC Steering Committee on 15 December 2012 in Tokyo. This describes the successful establishment of the key ILC technologies, as well as advances in the detector R&D and physics studies. Although not released by the time of the NSS meeting, the TDR results served as the basis for the presentations at the special event. The chosen technologies – including SRF cavities with high gradients and state-of-the-art detector concepts – have reached a stage where, should governments decide in favour and a site be chosen, ILC construction could start almost immediately. The ILC TDR, which describes a cost-effective and mature design for an LC in the energy range 200–500 GeV, with a possible upgrade to 1 TeV, is the final deliverable for the GDE mandate.

The newly established Linear Collider Collaboration (LCC), with Lyn Evans as director, will carry out the next steps to integrate the ILC and CLIC efforts under one governance. One highlight in Anaheim was a talk on the physics of the LC by Hitoshi Murayama of the Kavli Institute for Mathematics and Physics of the Universe (IPMU) and future deputy-director for the LCC. He addressed the broader IEEE audience, reviewing how a “Higgs factory” (a 250 GeV machine) as the first phase of the ILC could elucidate the nature of the Higgs particle – complementary to the LHC. The power of the LC lies in its flexibility. It can be tuned to well defined initial states, allowing model-independent measurements from the Higgs threshold to multi-tera-electron-volt energies, as well as precision studies that could reveal new physics at a higher energy scale.

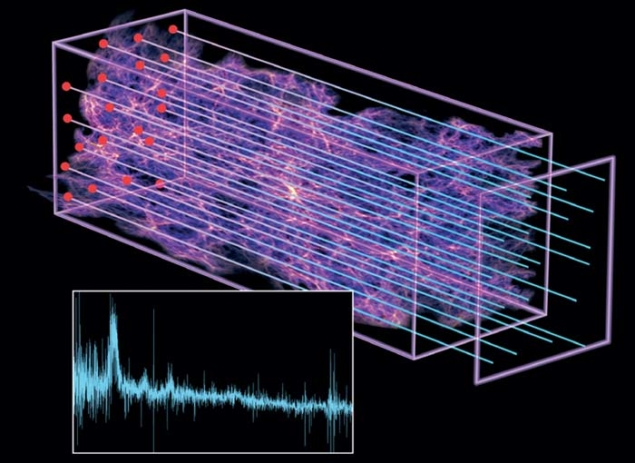

Image credit: ILC GDE.

Detailed technical reviews of the ILC and CLIC accelerator concepts and associated technologies followed the opening session. Nick Walker of DESY presented the benefits of using SRF acceleration with a focus on the “globalization” of the technology and the preparation for a worldwide industrial base for the ILC construction. The ultralow cavity-wall losses allow the use of long RF pulses, greatly simplifying the RF source while facilitating efficient acceleration of high-current beams. In addition, the low RF frequency (1.3 GHz) significantly reduces the impedance of the cavities, leading to reduced beam-dynamics effects and relatively relaxed alignment tolerances. More than two decades of R&D have led to a six-fold increase in the available voltage gradient, which – together with integration into a single cryostat (cryomodule) – has resulted in an affordable and mature technology. One of the most important goals of the GDE was to demonstrate that the SRF cavities can be reliably produced in industry. By the end of 2012, two ambitious goals were achieved: to produce cavities qualified at 35 MV/m and to demonstrate that an average gradient of 31.5 MV/m can be reached for ILC cryomodules. These high-gradient cavities have now been produced by industry with 90% yield, acceptable for ILC mass-production.

CERN’s Daniel Schulte reviewed progress with the CLIC concept, which is based on 12 GHz normal conducting accelerating structures and a two-beam scheme (rather than klystrons) for a cost-effective machine. The study has over the past two decades developed high-gradient, micron-precision accelerating structures that now reach more than 100 MV/m, with a breakdown probability of only 3 × 10–7 m–1 pulse–1 during high-power tests and more than 145 MV/m in two-beam acceleration tests at the CTF3 facility at CERN (tolerating higher breakdown rates). The CLIC design is compatible with energy-staging from the ILC baseline design of 0.5 TeV up to 3 TeV. The ILC and CLIC studies are collaborating closely on a number of technical R&D issues: beam delivery and final-focus systems, beam dynamics and simulations, positron generation, damping rings and civil engineering.

Another area of common effort is the development of novel detector technologies

Another area of common effort is the development of novel detector technologies. The ILC and CLIC physics programmes are both based on two complementary detectors with a “push–pull concept” to share the beam time between them. Hitoshi Yamamoto of Tohoku University reviewed the overall detector concepts and engineering challenges: multipurpose detectors for high-precision vertex and main tracking; a highly granular calorimeter inside a large solenoid; and power pulsing of electronics. The two ILC detector concepts (ILD and SiD) formed an excellent starting point for the CLIC studies. They were adapted for the higher-energy CLIC beams and ultra-short (0.5 ns) bunch-spacing by using calorimeters with denser absorbers, modified vertex and forward detector geometries, and precise (a few nanosecond) time-stamping to cope with increased beam-induced background.

Vertex detectors, a key element of the LC physics programme, were presented by Marc Winter of CNRS/IPHC Strasbourg. Their requirements address material budget, granularity and power consumption by calling for new pixel technologies. CCDs with 50 μm final pixels, CMOS pixel sensors (MIMOSA) and depleted field-effect transistor (DEPFET) devices have been developed successfully for many years and are suited to running conditions at the ILC. For CLIC, where much faster read-out is mandatory, the R&D concentrates on multilayer devices, such as vertically integrated 3D sensors comprising interconnected layers thinner than 10 μm, which allow a thin charge-sensitive layer to be combined with several tiers of read-out fabricated in different CMOS processes.

Both ILD and SiD require efficient tracking and highly granular calorimeters, optimized for particle-flow event reconstruction but differ in the central-tracking approach. ILD aims for a large time-projection chamber (TPC) in a 3.5–4 T field, while SiD is designed as a compact, all-silicon tracking detector with a 5 T solenoid. Tim Nelson of SLAC described tracking in the SiD concept with particular emphasis on power, cooling and minimization of material. Takeshi Matsuda of KEK presented progress on the low material-budget field cage for the TPC and end-plates based on micropattern gas detectors (GEMs, Micromegas or InGrid).

Apart from their dimensions, the electromagnetic calorimeters are similar for the ILC and CLIC concepts, as Jean-Claude Brient of Laboratoire Leprince-Ringuet explained. The ILD and the SiD detectors both rely on the silicon-tungsten sampling calorimeters, with emphasis on the separation of close electromagnetic showers. The use of small scintillator strips with silicon photodiodes operated in Geiger mode (SiPM) read-out as an active medium is being considered, as well as mixed designs using alternating layers of silicon and scintillator. José Repond of Argonne National Laboratory described the progress in hadron calorimetry, which is optimized to provide the best possible separation of energy deposits from neutral and charged hadrons. Two main options are under study: small plastic scintillator tiles with embedded SiPMs or higher granularity calorimeters based on gaseous detectors. Simon Kulis of AGH-UST Cracow addressed the importance of precise luminosity measurement at the LC and the challenges of the forward calorimetry.

Image credit: IEEE.

In the accelerator instrumentation domain, tolerances at CLIC are much tighter because of the higher gradients. Thibaut Lefevre of CERN, Andrea Jeremie of LAPP/CNRS and Daniel Schulte of CERN all discussed beam instrumentation, alignment and module control, including stabilization. Emittance preservation during beam generation, acceleration and focusing are key feasibility issues for achieving high luminosity for CLIC. Extremely small beam sizes of 40 nm (1 nm) in the horizontal (vertical) planes at the interaction point require beam-based alignment down to a few micrometres over several hundred metres and stabilization of the quadrupoles along the linac to nanometres, about an order of magnitude lower than ground vibrations.

Two sessions were specially organized to discuss potential spin-off from LC detector and accelerator technologies. Marcel Demarteau of Argonne National Laboratory summarized a study report, ILC Detector R&D: Its Impact, which points to the value of sustained support for basic R&D for instrumentation. LC detector R&D has already had an impact in particle physics. For example, the DEPFET technology is chosen as a baseline for the Belle-II vertex detector; an adapted version of the MIMOSA CMOS sensor provides the baseline architecture for the upgrade of the inner tracker in ALICE at the LHC; and construction of the TPC for the T2K experiment has benefited from the ILC TPC R&D programme.

The LC hadron calorimetry collaboration (CALICE) has initiated the large-scale use of SiPMs to read out scintillator stacks (8000 channels) and the medical field has already recognized the potential of these powerful imaging calorimeters for proton computed tomography. Erika Garutti of Hamburg University described another medical imaging technique that could benefit from SiPM technology – positron-emission tomography (PET) assisted by time-of-flight (TOF) measurement, with a coincidence-time resolution of about 300 ps FWHM, which is a factor of two better than devices available commercially. Christophe de La Taille of CNRS presented a number of LC detector applications for volcano studies, astrophysics, nuclear physics and medical imaging.

Accelerator R&D is vital for particle physics. A future LC accelerator would use high-technology coupled to nanoscale precision and control on an industrial scale. Marc Ross of SLAC introduced the session, “LC Accelerator Technologies for Industrial Applications”, with an institutional perspective on the future opportunities of LC technologies. The decision in 2004 to develop the ILC based on SRF cavities allowed an unprecedented degree of global focus and participation and a high level of investment, extending the frontiers of this “technology” in terms of performance, reliability and cost.

Particle accelerators are widely used as tools in the service of science with an ever growing number of applications to society

Particle accelerators are widely used as tools in the service of science with an ever growing number of applications to society. An overview of industrial, medical and security-related uses for accelerators was presented by Stuart Henderson of Fermilab. A variety of industrial applications makes use of low-energy beams of electrons, protons and ions (about 20,000 instruments) and some 9000 medical accelerators are in operation in the world. One example of how to improve co-ordination between basic and applied accelerator science is the creation of the Illinois Accelerator Research Centre (IARC). This partnership between the US Department of Energy and the State of Illinois aims to unite industry, universities and Fermilab to advance applications that are directly relevant to society.

SRF technology has potential in a number of industrial applications, as Antony Favale of Advanced Energy Systems explained. For example, large, high-power systems could benefit significantly using SRF, although the costs of cavities and associated cryomodules are higher than for room-temperature linacs; continuous-wave accelerators operating at reasonably high gradients benefit economically and structurally from SRF technology. The industrial markets for SRF accelerators exist for defence, isotope production and accelerator-driven systems for energy production and nuclear-waste mitigation. Walter Wuensch of CERN described how the development of normal-conducting linacs based on the high-gradient 100 MV/m CLIC accelerating structures may be beneficial for a number of accelerator applications, from X-ray free-electron lasers to industrial and medical linacs. Increased performance of high-gradient accelerating structures, translated into lower cost, potentially broadens the market for such accelerators. In addition, industrial applications increasingly require micron-precision 3D geometries, similar to the CLIC prototype accelerating structures. A number of firms have taken steps to extend their capabilities in this area, working closely with the accelerator community.

Steve Lenci of Communications and Power Industries LLC presented an overview of RF technology that supports linear colliders, such as klystrons and power couplers, and discussed the use of similar technologies elsewhere in research and industry. Marc Ross summarized applications of LC instrumentation, used for beam measurements, component monitoring and control and RF feedback.

The Advanced Accelerator Association Promoting Science & Technology (AAA) aims to facilitate industry-government-academia collaboration and to promote and seek industrial applications of advanced technologies derived from R&D on accelerators, with the ILC as a model case. Founded in Japan in 2008, its membership has grown to comprise 90 companies and 38 academic institutions. As the secretary-general Masanori Matsuoka explained, one of the main goals is a study on how to reach a consensus to implement the ILC in Japan and to inform the public of the significance of advanced accelerators and ILC science through social, political and educational events.

The Special Linear Collider Event ended with a forum that brought together directors of the high-energy-physics laboratories and leading experts in LC technologies, from both the academic research sector and industry. A panel discussion, moderated by Brian Foster of the University of Hamburg/DESY, included Rolf Heuer (CERN), Joachim Mnich (DESY), Atsuto Suzuki (KEK), Stuart Henderson (Fermilab), Hitoshi Murayama (IPMU), Steinar Stapnes (CERN) and Akira Yamamoto (KEK) .

The ILC has received considerable recent attention from the Japanese government. The round-table discussion therefore began with Suzuki’s presentation of the discovery of a Higgs-like particle at CERN and the emerging initiative toward hosting an ILC in Japan. The formal government statement, which is expected within the next few years, will provide the opportunity for the early implementation of an ILC and the recent discovery at CERN is strong motivation for a staged approach. This would begin with a 250 GeV machine (a “Higgs factory”), with the possibility of increasing in energy in a longer term. Suzuki also presented the Japan Policy Council’s recommendation, Creation of Global Cities by hosting the ILC, which was published in July 2012.

The discussion then focused on three major issues: the ILC Project Implementation Plan; the ILC Technology Roadmap; and the ILC Added Value to Society. While the possibility of implementing CLIC as a project at CERN to follow the LHC was also on the table, there was less urgency for discussion because the ILC effort counts on an earlier start date. The panellists exchanged many views and opinions with the audience on how the ILC international programme could be financed and how regional priorities could be integrated into a consistent worldwide strategy for the LC. Combining extensive host-lab-based expertise together with resources from individual institutes around the world is a mandatory first step for LC construction, which will also require the development of links between projects, institutions, universities and industry in an ongoing and multifaceted approach.

SRF systems – the central technology for the ILC – have many applications, so a worldwide plan for distributing the mass production of the SRF components is necessary, with technology-transfer proceeding in parallel, in partnership with funding agencies. Another issue discussed related to the model of global collaboration between host/hub-laboratories and industry to build the ILC, where each country shares the costs and human resources. Finally, accelerator and detector developments for the LC have already penetrated many areas of science. The question is how to improve further the transfer of technology from laboratories, so as to develop viable, on-going businesses that serve as a general benefit to society; as in the successful examples, such the IARC facility and the PET-TOF detector, presented in Anaheim.

Last, but not least, this technology-oriented symposium would have been impossible without the tireless efforts of the “Special LC Event” programme committee: Jim Brau, University of Oregon, Juan Fuster (IFIC Valencia), Ingrid-Maria Gregor (DESY Hamburg), Michael Harrison (BNL), Marc Ross (FNAL), Steinar Stapnes (CERN), Maxim Titov (CEA Saclay), Nick Walker (DESY Hamburg), Akira Yamamoto (KEK) and Hitoshi Yamamoto (Tohoku University). In all, this event was considered a real success. More than 90% of participants who answered the conference questionnaire rated it extremely important.

The IEEE tradition

The 2012 Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Nuclear Science Symposium (NSS) and Medical Imaging Conference (MIC) together with the Workshop on Room-Temperature Semiconductor X-Ray and Gamma-Ray Detectors took place at the Disneyland Hotel, Anaheim, California, on 29 October – 3 November. Having received over 850 NSS abstracts – a record number of NSS submissions for the conferences in North America – the 2012 IEEE NSS/MIC Symposium attracted more than 2200 attendees. The NSS series, which started in 1954, offers an outstanding opportunity for detector physicists and other scientists and engineers interested in the fields of nuclear science, radiation detection, accelerators, high-energy physics, astrophysics and related software. During the past decade the symposium has become the largest annual event in the area of nuclear and particle-physics instrumentation, providing an international forum to discuss the science and technology of large-scale experimental facilities at the frontiers of research.

• Lori Ann White, SLAC.