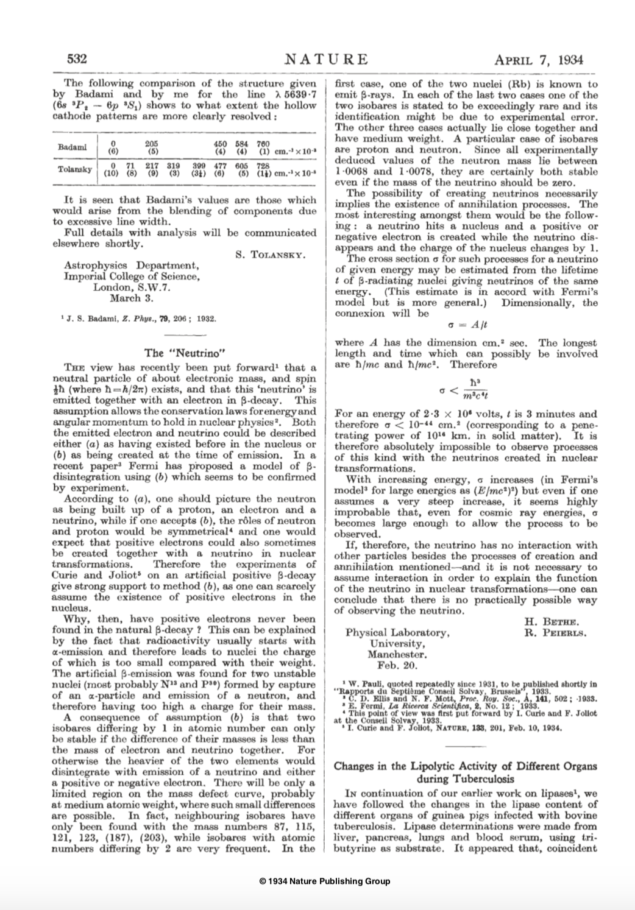

On 7 April 1934, the journal Nature published a paper – The “Neutrino” – in which Hans Bethe and Rudolf Peierls considered some of the consequences of Wolfgang Pauli’s proposal that a lightweight neutral, spin 1/2 particle is emitted in beta decay together with an electron (Bethe and Peierls 1934). Enrico Fermi had only recently put forward his theory of beta decay, in which he considered both the electron and the neutral particle – the neutrino – not as pre-existing in the nucleus, but as created at the time of the decay. As Bethe and pointed out, such a creation process implies annihilation processes, in particular one in which a neutrino interacts with a nucleus and disappears, giving rise to an electron (or positron) and a different nucleus with a charge changed by one unit. They went on to estimate the cross-section for such a reaction and argued that for a neutrino energy of 2.3 MeV it would be less than 10–44 cm2 – “corresponding to a penetrating power of 1014 km in solid matter”. This led them to conclude that even with a cross-section rising with energy as expected in Fermi’s theory, “it seems highly improbable that, even for cosmic ray energies, the cross-section becomes large enough to allow the process to be observed”.

However, as Peierls commented 50 years later, they had not allowed for “the existence of nuclear reactors producing neutrinos in vast quantities” or for the “ingenuity of experimentalists” (Peierls 1983). These two factors combined to underpin the first observation of neutrinos by Clyde Cowan and Fred Reines at the Savannah River nuclear reactor in 1956, and during the following years the continuing ingenuity of the particle-physics community led to the production of neutrinos with much higher energies at particle accelerators. With the reasonably large numbers of neutrinos that could be produced at accelerators, and cross-sections increasing with energy, their measurement became a respectable line of research, and ingenious experimentalists began to turn neutrinos into a tool to investigate different aspects of particle physics. Following the idea of Mel Schwarz, studies with neutrino beams began at the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron at Brookhaven and at the Proton Synchrotron (PS) at CERN in the early 1960s, and were taken to higher energies at Fermilab and at CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron in the 1970s. They continue today, using high-intensity beams produced at Fermilab and the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex.

At CERN, the story began in earnest in 1963 with an intense neutrino beam provided courtesy of Simon van der Meer’s invention of the neutrino horn – a magnetic device that focuses the charged particles (pions and kaons) whose decays give rise to the neutrinos – coupled with a scheme for fast ejection of the proton beam from the PS devised by Berend Kuiper and Günther Plass in 1959. First in line to receive the neutrinos was the 500-litre Heavy-Liquid Bubble Chamber (HLBC) built by a team led by Colin Rammm

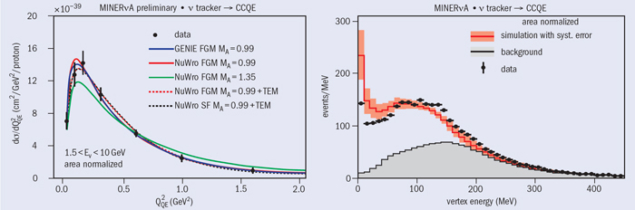

The combination worked well, allowing the measurement of neutrino cross-sections for various kinds of interactions. Studies of quasi-electric scattering, such as ν + n → μ + p, mirrored for the weak interaction – the only way that neutrinos can interact – measurements that had been made for several years in elastic electron-nucleon scattering at Stanford. The cross-sections measured in electron scattering were used to derive electromagnetic “form factors” – an expression of how much the scattering is “smeared out” by an extended object, in comparison with the expectation from point-like scattering. The early results from the HLBC showed the weak form factors to be similar to those measured in electron scattering. Electrons and neutrinos were apparently “seeing” the same thing in (quasi-)elastic scattering.

Less easy to understand at the time were the “deep” inelastic events where the nucleus was more severely disrupted and several pions produced, as in ν + N → μ + N + nπ. The measurements of such events revealed a cross-section that increased with neutrino energy, rising to more than 10 times the quasi-elastic cross-section. Don Perkins of Oxford University reported on these results at a conference in Siena in 1963. “They were clearly trying to tell us a very simple thing,” he recalled nearly 40 years later, “but unfortunately, we were just not listening!” (Perkins 2001)

Indeed, most physicists thought that this sub-structure (quarks) was more of a mathematical convenience

The following year, Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig put forward their ideas about a new substructure to matter – the “quarks” or “aces” that made up the hadrons, including the protons and neutrons of the nucleus. Today, this sub-structure is a fundamental part of the Standard Model of particle physics, and many young people learn about quarks as basic building blocks of matter while still at school. At the time, however, it was a different story because there was no evidence for real particles with charges of 1/3 and 2/3 that the proposals required. Indeed, most physicists thought that this sub-structure was more of a mathematical convenience.

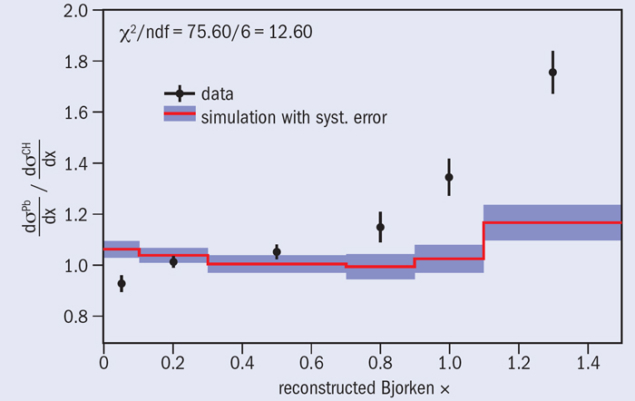

The picture began to change at a conference in Vienna in 1968, when deep-inelastic electron-scattering measurements at SLAC’s 3 km linear accelerator by the SLAC-MIT experiment – the direct descendent of the earlier experiments in Stanford – made people sit up and listen. The deep-inelastic cross-section divided by the cross-section expected from a point charge (Mott scattering) showed a surprisingly flat dependence on the square of the momentum transfer (q2). This was consistent with scattering from points within the nucleons rather than the smeared-out structure seen in elastic scattering, which gives a cross-section that falls away rapidly with q2. Moreover, the measurements yielded a structure function – akin to the form factor of elastic scattering – that depended very little on q2 at large values of energy transfer, ν. Indeed, the data appeared consistent with a proposal by James Bjorken that in the limit of high q2, the deep-inelastic structure functions would depend only on a dimensionless variable, x = q2/2Mν, for a target nucleon mass M. This behaviour, called “scaling”, implied point-like scattering.

What did this imply for neutrinos? If they really were seeing the same structure as electrons – if the deep-inelastic structure function depended only on the dimensionless variable x – then the total cross-section should simply rise linearly with neutrino energy. As soon as Perkins saw the first results from SLAC in 1968, he quickly revisited the data from the Heavy-Liquid Bubble Chamber and found that this was indeed the case (Perkins 2001).

The “points” in the nucleons became known as partons – a name coined by Richard Feynman, who had been trying to understand high-energy proton–proton collisions in terms of point-like constituents. A key question to be resolved was whether the partons had the attributes of quarks, such as spin 1/2 and the predicted fractional charges. The SLAC-MIT group went on to make an outstanding series of systematic measurements over the next couple of years, which provided undisputable evidence for the point-like structure within the nucleon – and led in 1990 to the award of the Nobel Prize in Physics to Jerome Friedman, Henry Kendall and Richard Taylor. This wealth of data included results that clearly indicated that the partons must have spin 1/2.

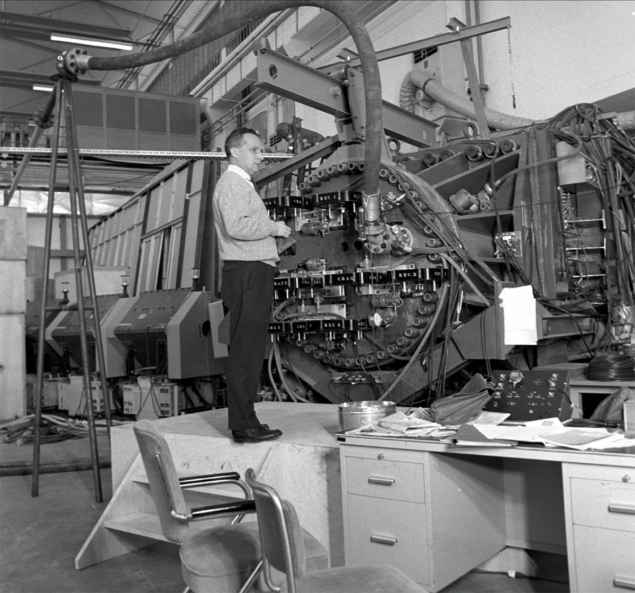

In the meantime, a new heavy-liquid bubble chamber had been installed at the PS at CERN. Gargamelle was 4.8 m long and contained 18 tonnes of Freon, and had been designed and built at Orsay under the inspired leadership of André Lagarrigue, of the Ecole Polytechnique. It was to become famous for the first observation of weak neutral currents in 1973 (CERN Courier September 2009 p25). The same year saw the first publication of total cross-sections measured in Gargamelle, based on a few thousand events, not only with neutrinos but also antineutrinos. The results had in fact been aired first the previous year at Fermilab, at the 16th International Conference on High-Energy Physics (ICHEP). They showed clearly the linear rise with energy consistent with point-like scattering. Moreover, the neutrino cross-section was around three times larger than that for antineutrinos, which confirmed that neutrinos and antineutrinos were also seeing structure with spin 1/2.

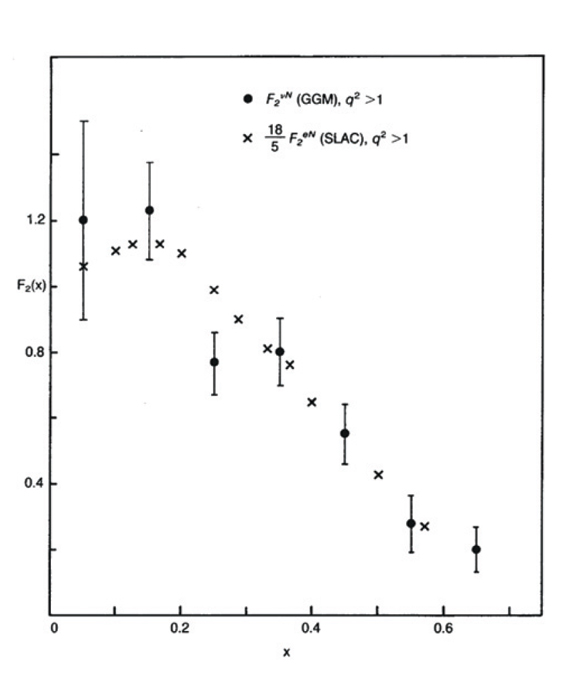

However, there was still more. With data from both neutrinos and antineutrinos, the team could derive one of the structure functions that was also measured in deep-inelastic electron-scattering. Electrons scatter electromagnetically in proportion to the square of the charge of whatever is doing the scattering. Neutrinos, by contrast, are blind to charge and scatter only weakly. A comparison of the two structure functions should depend only on the mean charge squared seen by the electrons, which for quarks of charges 2/3 and –1/3 in equal numbers in the deuterium target used in the experiment at SLAC would be 5/18. So, the structure function from neutrino scattering, with no charge dependence, should be 18/5 of that for electron-scattering. As Feynman himself said: ” If you never did believe that ‘nonsense’ that quarks have non-integral charges, we have a chance now, in comparing neutrino to electron scattering, to finally discover for the first time whether the idea…is physically sensible, physically sound; that’s exciting.” (Feynman 1974)

At the 17th ICHEP held in London in 1974, particle physicists from around the world were able to see the results from Gargamelle for themselves – the neutrino structure function, when multiplied by 18/5, did indeed fit closely with the data from the SLAC-MIT experiment (see figure). Forty years on from the paper by Bethe and Peierls, neutrino cross-sections were not only being measured, they were revealing a more fundamental layer to nature – the quarks.

These early experiments were just the beginning of what became a prodigious effort, mainly at CERN and Fermilab, using neutrinos to probe the structure of the nucleon within the context of quantum chromodynamics, the theory of quarks and the gluons that bind them together. And the effort is not finished, because neutrinos are still being used to understand puzzles that remain in the structure of the nucleus. But that is another story.