Since the discovery of the positron in 1932 and the antiproton in 1955, physicists have striven to confront the properties of leptonic and baryonic matter and antimatter. A major advance in the story took place in 1995 when the first antihydrogen atoms were observed at CERN’s LEAR facility. Then, in 2002, the ATHENA and ATRAP collaborations produced cold (trappable) antihydrogen at CERN’s Antiproton Decelerator (AD), paving the way to the first measurement of antihydrogen’s atomic transitions. An intense research programme at the AD has followed to compare the atomic states of antimatter with the most well-known atomic transitions in matter.

The physical properties of antimatter particles are tightly constrained within the Standard Model of particle physics (SM). For all local Lorentz-invariant quantum-field theories of point-like particles like the SM, the combination of the discrete symmetries charge-conjugation, parity and time-reversal (CPT) is conserved. An implication of the CPT theorem is that the properties of matter and antimatter are equal in absolute value. In this respect the lack of observation of primordial antimatter in the universe is tantalising, hinting that the universe has a preference for matter over antimatter despite their perfect symmetry on the microscopic scale as imposed by the SM. Although violations of CP symmetry, from which an imbalance in matter and antimatter can arise, have been observed in several systems, the effect is many orders of magnitude too small to account for the observed cosmological mismatch.

In the quest for a quantitative explanation to the baryon asymmetry in the universe, one could question the validity of our formulation of the laws of physics in terms of quantum-field theory. This is additionally motivated by the notable absence of the gravitational force in the SM and would suggest that CPT symmetry (or Lorentz invariance) need not be conserved. A framework called Standard Model Extension (SME), an effective field theory that contains the SM and general relativity but also possible CPT and Lorentz violating terms, allows researchers to interpret the results of experiments designed to search for such effects.

Any measurement with antihydrogen atoms constitutes a model-independent test of CPT invariance. Given the precision at which they have been measured in hydrogen, two atomic transitions in antihydrogen are of particular interest: the 1S–2S transition and the ground-state hyperfine splitting (which corresponds to the 21 cm microwave-emission line between parallel and antiparallel antiproton and positron spins). These were determined over the past few decades in hydrogen with an absolute (relative) precision of 10 Hz (4 × 10–15) and 2 mHz (1.4 × 10–12), respectively. Reaching similar precision in antihydrogen, hydrogen’s CPT conjugate would provide one of the most sensitive CPT tests in what was until recently a yet unprobed atomic domain. But this is a daunting challenge.

Status and prospects

Measurements of the hyperfine splitting of hydrogen reached their apogee in the 1970s. It is only recently that interest in such measurements has been revived, motivated by the possibility to further develop methods that can be applied to antihydrogen. Hydrogen’s hyperfine splitting was originally measured using a maser to interrogate atoms held in a Teflon-coated storage bulb, but this technique is not transferable to antihydrogen because unavoidable interactions between the antiatoms and the walls would lead to annihilations.

A precision of a few Hz can, however, be envisioned using the “beam-resonance” method of Rabi. This technique involves a polarised beam, microwave fields to drive spin flips, magnetic-field gradients to select a spin state, and a detector to measure the flux of atoms as a function of the microwave frequency. While less precise than the maser technique, the in-beam method can be directly applied to antihydrogen with a foreseen initial precision of a few kHz (10–6 relative precision). The leading order of the hyperfine splitting can be calculated from the known properties of the antiproton and positron, but a 10–6 level measurement would be sensitive to the antiproton magnetic and electric form factors that are so far unknown.

Earlier this year, the ALPHA experiment at CERN’s AD measured the hyperfine splitting of trapped antihydrogen. Following a long campaign that saw ALPHA determine antihydrogen’s 1S–2S transition in 2016 (CERN Courier January/February 2017 p8), the collaboration achieved a precision of 4 × 10–4 (0.5 MHz) on the hyperfine measurement. Ultimately the precision of in-trap measurements will be limited by the presence of strong magnetic-field gradients, however. The in-beam technique, by contrast, probes the hyperfine transition far away from the strong inhomogeneous magnetic trapping fields. In the 1950s this technique enabled hydrogen’s hyperfine structure to be determined to a precision of 50 Hz. The recent measurement of this transition by the ASACUSA experiment using a similar technique has now improved on this precision by more than an order of magnitude.

The ASACUSA collaboration was formed in 1997 to investigate antiprotonic atoms and collisions involving slow antiprotons. Its antihydrogen programme started in 2005 at the AD and in recent years the collaboration has focused on two topics. One is laser spectroscopy of antiprotonic helium, which allows the determination of the antiproton mass (CERN Courier September 2011 p7) and the antiproton magnetic moment. The latter value was recently measured to higher precision in Penning traps first by the ATRAP experiment (CERN Courier May 2013 p6) and, as announced in October, further improved by more than three orders of magnitude by the BASE experiment, both also located at the AD.

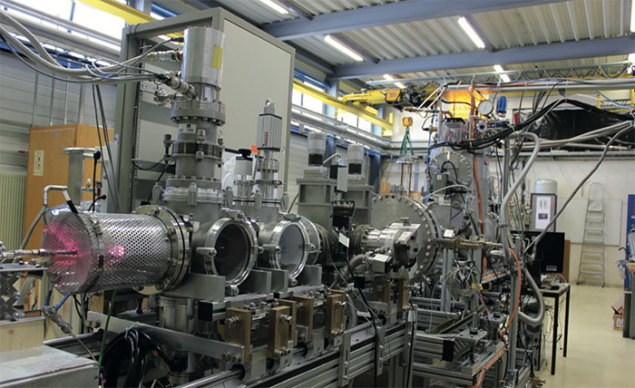

The second focus of ASACUSA, led by the CUSP group, is to measure the hyperfine structure of antihydrogen in a polarised beam. ASACUSA employs a multi-trap set-up to produce an antihydrogen beam (CERN Courier March 2014 p5) for Rabi-type spectroscopy on the hyperfine transition. The spectroscopy apparatus was designed to match the expected properties of an antihydrogen beam and called for a test of the apparatus with a hydrogen beam of similar characteristics.

Hydrogen first

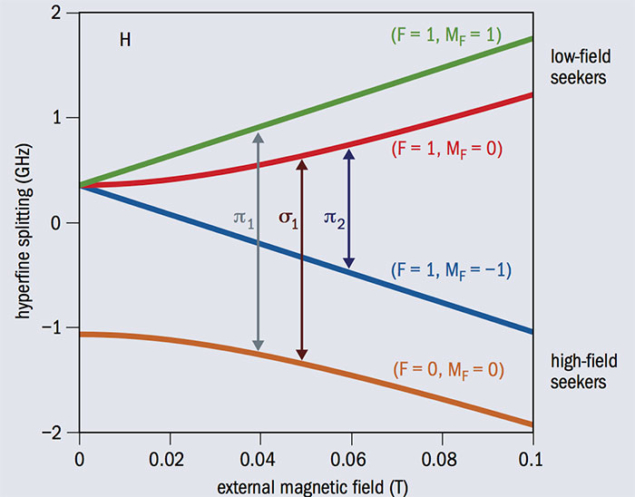

The spectroscopy technique relies on the dependency of the atomic energy levels on a magnetic field, also known as the Zeeman effect (figure 1). In the presence of a magnetic field, the degeneracy of the hyperfine triplet states is lifted. Two of the states, called low-field seekers (lfs), have a rising energy with rising magnetic field, while the third state of the triplet and the singlet state decrease their energies with rising magnetic field (they are called high-field seekers, hfs). These distinguishing properties are used to first polarise the beam by means of a magnetic-field gradient (figure 2), which leads to opposite forces on lfs and hfs. As a result, only lfs arrive at the interaction region, where a microwave cavity provides an oscillating magnetic field. This field can then induce state conversions from lfs to hfs if tuned to the right frequency. Atoms in hfs states are subsequently removed from the beam by a second section of magnetic-field gradients, thus leading to a reduced count rate at the detector when the transition is induced.

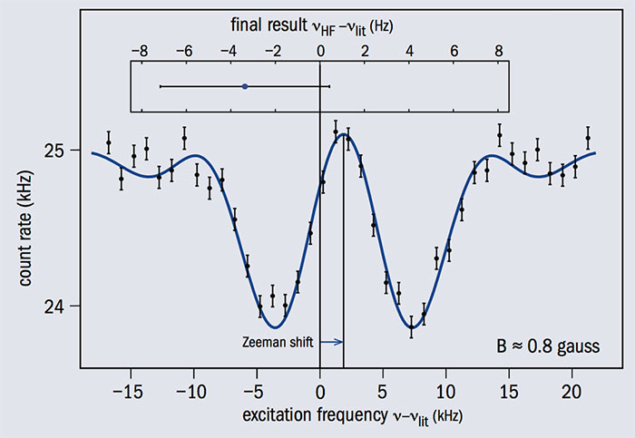

In the apparatus design chosen, large geometrical openings compensate for the low antihydrogen flux and a superconducting magnet is used to generate sufficiently selective magnetic-field gradients over such a large area. The oscillating microwave field needed to drive the hyperfine transition must be homogenous over the large geometrical opening, which dictated the design of the cavity leading to a particular resonance spectrum (figure 3). The functionality of the spectroscopy apparatus and other technical developments were tested by coupling a cold and polarised hydrogen source and a quadrupole mass spectrometer as hydrogen detector to the spectroscopy apparatus envisioned for the antihydrogen experiment (figure 2).

The measurement led to the determination of the hydrogen’s so-called σ1 hyperfine transition (figure 1), the transition frequency of which was measured as a function of an externally applied magnetic field. From a set of frequency determinations, the zero-field value could be extracted and such measurements were repeated under 10 distinct conditions to investigate systematic effects. In total more than 500 resonances (an example is shown in figure 3) were acquired to extract the zero-field hydrogen ground-state hyperfine splitting. Numerical methods developed to assist the analysis of the transition line shape contributed to the improvement by more than an order of magnitude, leading to a precision of 3.8 Hz and a value consistent with the more precise maser result.

A measurement of hydrogen’s hyperfine splitting at the Hz level implies an absolute precision of 10–15 eV. Given the scarcity of antihydrogen and the yet unprobed properties (namely velocity and atomic states) of the antihydrogen beam, a measurement at this level of precision on antihydrogen is not possible in the short-term. However, the analysis of ASACUSA data collected with hydrogen enabled the collaboration to assess the necessary number of antiatoms to reach a 10–6 sensitivity, assuming plausible beam properties. The conclusion is that a measurement at the peV level (kHz precision) should be possible if 8000 antiatoms can be detected after the spectrometer. That would require at least an order-of-magnitude increase in the antihydrogen flux.

The Rabi-type spectroscopy approach chosen by ASACUSA has the capability to test individual transitions in hydrogen and antihydrogen under well-controlled external conditions and, if successful, will immediately result in a precision of 10–6 or better. At this level, the hyperfine transitions would provide yet unknown information on the internal structure of the antiproton. However, much work remains to be done for the ASACUSA experiment to gather the needed number of antihydrogen atoms in a reasonable time.

Until then, more measurements can be performed with the hydrogen set-up. The apparatus has recently been modified to allow for the simultaneous measurement of σ1 and π1 transitions (figure 1). Within the SME, the latter transition could reveal CPT and Lorentz violations while the σ1 transition is insensitive to these effects and would serve as a monitor of potential systematic errors. This would give access to a number of so-far-unconstrained SME parameters that can be probed by hydrogen alone. While the antihydrogen experiment focuses on increasing the cold, ground- state antihydrogen flux, the hydrogen experiment is about to start a new measurement campaign for which results are expected in the next 18–24 months. The hydrogen atom has been a source of profound theoretical developments for some time, and history has shown that it is well worth the effort to study it ever more closely.