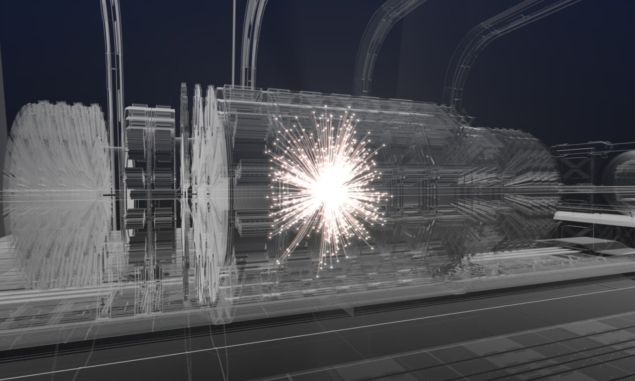

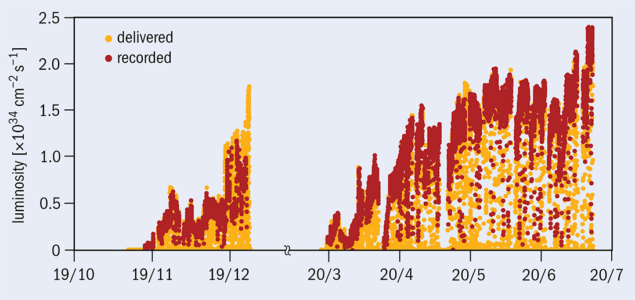

A new record for the highest luminosity at a particle collider has been set by SuperKEKB at the KEK laboratory in Tsukuba, Japan. On 15 June, electron–positron collisions at the 3 km-circumference double-ring collider reached an instantaneous luminosity of 2.22×1034 cm-2 s-1 — surpassing the LHC’s record of 2.14×1034 cm-2s-1 set with proton–proton collisions in 2018. A few days later, SuperKEKB pushed the luminosity record to 2.4×1034 cm-2s-1. This milestone follows more than two years of commissioning of the new machine, which delivers asymmetric electron–positron collisions to the Belle II detector at energies corresponding to the Υ(4S) resonance (10.57 GeV) to produce copious amounts of B and D mesons and τ leptons.

We can spare no words in thanking KEK for their pioneering work in achieving results that push forward both the accelerator frontier and the related physics frontier

Pantaleo Raimondi

SuperKEKB is an upgrade of the KEKB b-factory, which operated from 1998 until June 2010 and held the luminosity record of 2.11×1034 cm−2s−1 for almost ten years until the LHC edged past it. SuperKEKB’s new record was achieved with a product of beam currents less than 25% of that at KEKB thanks to a novel “nano-beam” scheme originally proposed by accelerator physicist Pantaleo Raimondi of the ESRF, Grenoble. The scheme, which works by focusing the very low-emittance beams using powerful magnets at the interaction point, squeezes the vertical height of the beams at the collision point to about 220 nm. This is expected to decrease to approximately 50 nm by the time SuperKEKB reaches its design performance.

“We, as the accelerator community, have been working together with the KEK team since a very very long time and we can spare no words in thanking KEK for their pioneering work in achieving results that push forward both the accelerator frontier and the related physics frontier,” says Raimondi.

The first collider to employ the nano-beam scheme and to achieve a β*y focusing parameter of 1 mm, SuperKEKB required significant upgrades to KEKB including a new low-energy ring beam pipe, a new and complex system of superconducting final-focusing magnets, a positron damping ring, and an advanced injector. The most recent improvement, completed in April, was the introduction of crab-waist technology, which stabilises beam-beam blowup using carefully tuned sextupole magnets located symmetrically on either side of the interaction point (IP). It was first used at DAΦNE, which had much less demanding tolerances than SuperKEKB, and differs from the “crab-crossing” technology based on special radio-frequency cavities which was used to boost the luminosity at KEKB and is now being implemented at CERN for the high-luminosity LHC.

This luminosity milestone marks the start of the super B-factory era

Yukiyoshi Ohnishi

“The vertical beta at the IP is 1 mm which is the smallest value for colliders in the world. Now we are testing 0.8 mm,” says Yukiyoshi Ohnishi, commissioning leader for SuperKEKB. “The difference between DAΦNE and SuperKEKB is the size of the Piwinski angle, which is much larger than 1 as found in ordinary head-on or small crossing-angle colliders.”

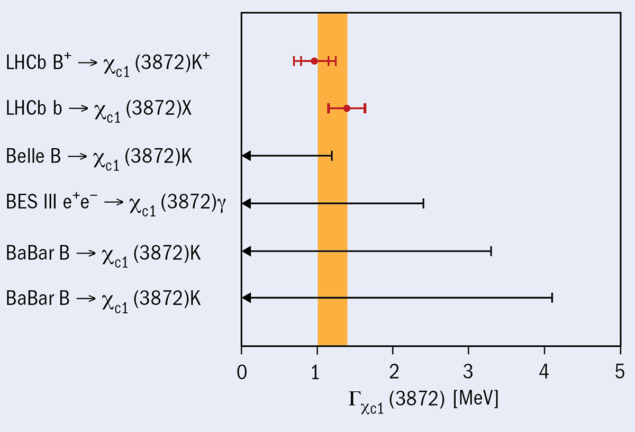

In the coming years, the luminosity of SuperKEKB is to be increased by a factor of around 40 to reach its design target of 8×1035 cm−2s−1. This will deliver to Belle II, which produced its first physics result in April, around 50 times more data than its predecessor, Belle, at KEKB over the next ten years. The large expected dataset, containing about 50 billion B-meson pairs and similar numbers of charm mesons and tau leptons, will enable Belle II to study rare decays and test the Standard Model with unprecedented precision, allowing deeper investigations of the flavour anomalies reported by LHCb and sensitive searches for very weakly interacting dark-sector particles.

“This luminosity milestone, which was the result of extraordinary efforts of the SuperKEKB and Belle II teams, marks the start of the super B-factory era. It was a special thrill for us, coming in the midst of a global pandemic that was difficult in so many ways for work and daily life,” says Ohnishi. “In the coming years, we will significantly increase the beam currents and focus the beams even harder, reducing the β*y parameter far below 1 mm. However, there will be many more difficult technical challenges on the long road ahead to design luminosity, which is expected towards the end of the decade.”

The crab-waist scheme is also envisaged for a possible Super Tau Charm factory and for the proposed Future Circular Collider (FCC-ee) at CERN, says Raimondi. “For both these projects there is a solid design based on this concept and in general all circular lepton colliders are apt to take benefit from it.”