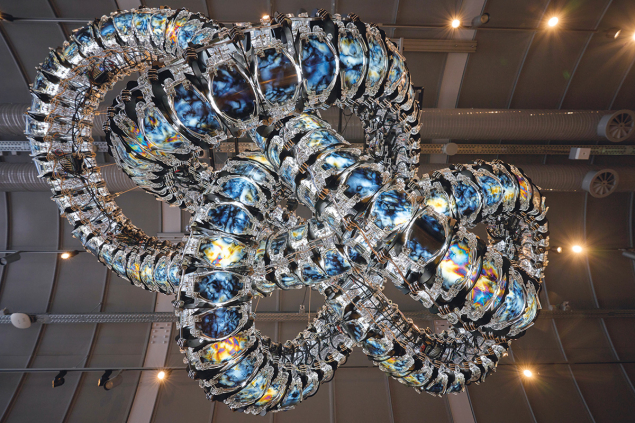

Over the past 10 years, Mónica Bello facilitated hundreds of encounters between artists and scientists as curator of the Arts at CERN programme. As she steps down, she shares her reflections on the symbiotic relationship between two disciplines united by insatiable curiosity.

Why should scientists care about art?

Throughout my experiences in the laboratory, I have seen how art is an important part of a scientist’s life. By being connected with art, scientists recognise that their activities are very embedded in contemporary culture. Science is culture. Through art and dialogues with artists, people realise how important science is for society and for culture in general. Science is an important cultural pillar in our society, and these interactions bring scientists meaning.

Are science and art two separate cultures?

Today, if you ask anyone: “What is nature?” they describe everything in scientific terms. The way you describe things, the mysteries of your research: you are actually answering the questions that are present in everyone’s life. In this case, scientists have a sense of responsibility. I think art helps to open this dialogue from science into society.

Do scientists have a responsibility to communicate their research?

All of us have a social responsibility in everything we produce. Ideas don’t belong to anyone, so it’s a collective endeavour. I think that scientists don’t have the responsibility to communicate the research themselves, but that their research cannot be isolated from society. I think it’s a very joyful experience to see that someone cares about what you do.

Why should artists care about science?

If you go to any academic institution, there’s always a scientific component, very often also a technological one. A scientific aspect of your life is always present. This is happening because we’re all on the same course. It’s a consequence of this presence of science in our culture. Artists have an important role in our society, and they help to spark conversations that are important to everyone. Sometimes it might seem as though they are coming from a very individual lens, but in fact they have a very large reach and impact. Not immediately, not something that you can count with data, but there is definitely an impact. Artists open these channels for communicating and thinking about a particular aspect of science, which is difficult to see from a scientific perspective. Because in any discipline, it’s amazing to see your activity from the eyes of others.

Creativity and curiosity are the parameters and competencies that make up artists and scientists

A few years back we did a little survey, and most of the scientists thought that by spending time with artists, they took a step back to think about their research from a different lens, and this changed their perspective. They thought of this as a very positive experience. So I think art is not only about communicating to the public, but about exploring the personal synergies of art and science. This is why artists are so important.

Do experimental and theoretical physicists have different attitudes towards art?

Typically, we think that theorists are much more open to artists, but I don’t agree. In my experiences at CERN, I found many engineers and experimental physicists being highly theoretical. Both value artistic perspectives and their ability to consider questions and scientific ideas in an unconventional way. Experimental physicists would emphasise engagement with instruments and data, while theoretical physicists would focus on conceptual abstraction.

By being with artists, many experimentalists feel that they have the opportunity to talk about things beyond their research. For example, we often talk about the “frontiers of knowledge”. When asked about this, experimentalists or theoretical physicists might tell us about something other than particle physics – like neuroscience, or the brain and consciousness. A scientist is a scientist. They are very curious about everything.

Do these interactions help to blur the distinction between art and science?

Well, here I’m a bit radical because I know that creativity is something we define. Creativity and curiosity are the parameters and competencies that make up artists and scientists. But to become a scientist or an artist you need years of training – it’s not that you can become one just because you are a curious and creative person.

Not many people can chat about particle physics, but scientists very often chat with artists. I saw artists speaking for hours with scientists about the Higgs field. When you see two people speaking about the same thing, but with different registers, knowledge and background, it’s a precious moment.

When facilitating these discussions between physicists and artists, we don’t speak only about physics, but about everything that worries them. Through that, grows a sort of intimacy that often becomes something else: a friendship. This is the point at which a scientist stops being an information point for an artist and becomes someone who deals with big questions alongside an artist – who is also a very knowledgeable and curious person. This is a process rich in contrast, and you get many interesting surprises out of these interactions.

But even in this moment, they are still artists and scientists. They don’t become this blurred figure that can do anything.

Can scientific discovery exist without art?

That’s a very tricky question. I think that art is a component of science, therefore science cannot exist without art – without the qualities that the artist and scientist have in common. To advance science, you have to create a question that needs to be answered experimentally.

Did discoveries in quantum mechanics affect the arts?

Everything is subjected to quantum mechanics. Maybe what it changed was an attitude towards uncertainty: what we see and what we think is there. There was an increased sense of doubt and general uncertainty in the arts.

Do art and science evolve together or separately?

I think there have been moments of convergence – you can clearly see it in any of the avant garde. The same applies to literature; for example, modernist writers showed a keen interest in science. Poets such as T S Eliot approached poetry with a clear resonance of the first scientific revolutions of the century. There are references to the contributions of Faraday, Maxwell and Planck. You can tell these artists and poets were informed and eager to follow what science was revealing about the world.

You can also note the influence of science in music, as physicists get a better understanding of the physical aspects of sound and matter. Physics became less about viewing the world through a lens, and instead focused on the invisible: the vibrations of matter, electricity, the innermost components of materials. At the end of the 19th and 20th centuries, these examples crop up constantly. It’s not just representing the world as you see it through a particular lens, but being involved in the phenomena of the world and these uncensored realities.

From the 1950s to the 1970s you can see these connections in every single moment. Science is very present in the work of artists, but my feeling is that we don’t have enough literature about it. We really need to conduct more research on this connection between humanities and science.

What are your favourite examples of art influencing science?

Feynman diagrams are one example. Feynman was amazing – a prodigy. Many people before him tried to represent things that escaped our intuition visually and failed. We also have the Pauli Archives here at CERN. Pauli was not the most popular father of quantum mechanics, but he was determined to not only understand mathematical equations but to visualise them, and share them with his friends and colleagues. This sort of endeavour goes beyond just writing – it is about the possibility of creating a tangible experience. I think scientists do that all the time by building machines, and then by trying to understand these machines statistically. I see that in the laboratory constantly, and it’s very revealing because usually people might think of these statistics as something no one cares about – that the visuals are clumsy and nerdy. But they’re not.

Even Leonardo da Vinci was known as a scientist and an artist, but his anatomical sketches were not discovered until hundreds of years after his other works. Newton was also paranoid about expressing his true scientific theories because of the social standards and politics of the time. His views were unorthodox, and he did not want to ruin his prestigious reputation.

Today’s culture also influences how we interpret history. We often think of Aristotle as a philosopher, yet he is also recognised for contributions to natural history. The same with Democritus, whose ideas laid foundations for scientific thought.

So I think that opening laboratories to artists is very revealing about the influence of today’s culture on science.

When did natural philosophy branch out into art and science?

I believe it was during the development of the scientific method: observation, analysis and the evolution of objectivity. The departure point was definitely when we developed a need to be objective. It took centuries to get where we are now, but I think there is a clear division: a line with philosophy, natural philosophy and natural history on one side, and modern science on the other. Today, I think art and science have different purposes. They convene at different moments, but there is always this detour. Some artists are very scientific minded, and some others are more abstract, but they are both bound to speculate massively.

It’s really good news for everyone that labs want to include non-scientists

For example, at our Arts at CERN programme we have had artists who were interested in niche scientific aspects. Erich Berger, an artist from Finland, was interested in designing a detector, and scientists whom he met kept telling him that he would need to calibrate the detector. The scientist and the artist here had different goals. For the scientist, the most important thing is that the detector has precision in the greatest complexity. And for the artist, it’s not. It’s about the process of creation, not the analysis.

Do you think that science is purely an objective medium while art is a subjective one?

No. It’s difficult to define subjectivity and objectivity. But art can be very objective. Artists create artefacts to convey their intended message. It’s not that these creations are standing alone without purpose. No, we are beyond that. Now art seeks meaning that is, in this context, grounded in scientific and technological expertise.

How do you see the future of art and science evolving?

There are financial threats to both disciplines. We are still in this moment where things look a bit bleak. But I think our programme is pioneering, because many scientific labs are developing their own arts programmes inspired by the example of Arts at CERN. This is really great, because unless you are in a laboratory, you don’t see what doing science is really about. We usually read science in the newspapers or listen to it on a podcast – everything is very much oriented to the communication of science, but making science is something very specific. It’s really good news for everyone that laboratories want to include non-scientists. Arts at CERN works mostly with visual artists, but you could imagine filmmakers, philosophers, those from the humanities, poets or almost anyone at all, depending on the model that one wants to create in the lab.