Embedded in 3 km-thick ice, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole needs permanent human company to keep it operational. Recent IceCube “winterover” Marc Jacquart shares his experience of working in a cool but hostile environment.

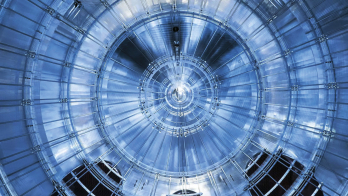

IceCube’s 5160 optical sensors positioned deep within the Antarctic ice detect around 100,000 neutrinos per year, some of which are the most energetic events ever recorded. To make sure that the detector is operational throughout the year, people are required to spend extended periods at the South Pole, where temperatures are on average around –60°C during the winter.

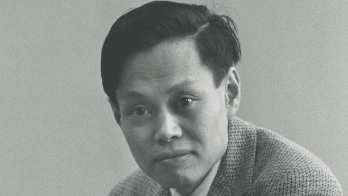

Marc Jacquart was one of two “winterovers” for IceCube during the season November 2022 to November 2023. Having completed his master’s degree, during which he analysed IceCube data, he saw an internal email about the position and applied: “It was a long-time dream-come-true. I had wanted to go to the South Pole since I heard about IceCube six years earlier.” First he had to pass medical tests, a routine requirement for winterovers because it is difficult to evacuate people during the winter. His next stop was the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the lead institution for the IceCube collaboration, where he and his colleague Hrvoje Dujmović received three months’ training on how to operate, troubleshoot, calibrate and repair IceCube’s hardware and software components using a small replica of the data centre. “Our job is to ensure the highest detector uptime, so we need to know how to fix a problem immediately if something breaks.”

The pair made their way to McMurdo Station on the shores of Antarctica closest to New Zealand in early November 2022. From there, a plane took them 1350 km to the Amundsen–Scott station, located 2835 m above sea level and only 150 m from the geographic South Pole. During the summer, up to 150 people stay at the station to make major repairs and upgrades to the research facilities, which also include the South Pole Telescope, BICEP and an atmospheric research observatory. By mid-February, most people leave. “We were only 43 winterovers left, and that’s when you can help each other and busy yourself with all kinds of things,” says Marc.

Part of station life is volunteering for teams, which in Marc’s case included the fire fighters, amongst others. To bide their time during a nearly six-month-long night, the inhabitants can go to the library, music room or grow vegetables in a repurposed biology experiment to freshen up the preserved foods. While winter in the Antarctic Circle is harsh outside, says Marc, it has one major highlight: the southern lights. “I remember one time, they were just dancing, moving and very bright. We stayed outside for a full hour packed in layers and layers of clothes!”

The only real downtime for the detector is when operators perform a full restart every 32 hours

As a winterover, Marc ensured that the IceCube detector worked 24/7 and recorded every incoming neutrino. “Usually, we have 99.9% uptime. If there is something wrong, we have a pager that pings us, even in the middle of the night.” To ensure that the rarest high-energy neutrinos are recorded, the only real downtime for the detector, he says, is when operators perform a full restart every 32 hours. For such events, which could point to high-energy phenomena in the universe, IceCube sends a real-time alert to other experiments. About 200 machines are located in the data centre and collect 1 TB of data per day, only 10% of which are sent north to a data centre in the US due to satellite-bandwidth limitations. The remaining data gets stored on hard drives, which must be swapped manually by the winterovers every two weeks. During the summer, when aircraft can reach the South Pole on a regular basis, boxes stashed with hard drives are taken back for thorough data analysis and archiving.

Since returning home to Switzerland, Marc is considering his next steps. “I have the opportunity to work on a radio observatory in the US next year. After a year operating the IceCube detector, I’m interested to work with hardware more. And I am definitely considering a PhD with IceCube afterwards, as there is a lot coming up.” Currently, the IceCube collaboration is working towards IceCube-Gen2, with the first step being to add seven strings with improved optical modules to the existing underground complex. In a second step, 120 further cables with refined light sensors will optimise the detector, and two radio detectors as well as an extended array will be placed on the surface. The upgrades will enlarge IceCube’s coverage from one to eight cubic kilometres, offering more than enough tasks for future winterovers during the decade . “Maybe in a few years I would be keen to return to the South Pole. It’s a very special place.”