Outreach can take many shapes and forms, and can be performed successfully by trained communicators and science enthusiasts. But its original form in particle physics – passionate researchers engaging directly with a wide range of the general public – remains as vivid and vital as ever. Claire Adam highlights key examples of this high-energy physics success story.

As recently as 10 years ago, scientists had to work hard to convince conference organisers of the value of sessions on communication, education and outreach. Today, major conferences such as ICHEP, EPS-HEP and LHCP not only offer parallel sessions, but also plenary talks where the state of the art in the field is reviewed. Abstracts from around the world describe events organised in multiple contexts and languages, via formal and informal partnerships between scientists and local communities, artists, teachers and many others. Each of the major LHC experiments now has a dedicated outreach group that, with the help of a few professional communicators, develops material and shares best practice within the collaboration. Institutes and funding agencies are on board, and younger generations are increasingly encouraged to include outreach on their CVs. A fraction of this energy and creativity is captured in reports, such as the one presented each year to the CERN Council by the International Particle Physics Outreach Group (IPPOG) – a collaboration initiated by former CERN Director-General Chris Llewellyn-Smith in the early days of the LHC project, and that now counts 33 countries, seven experiments and three large laboratories.

Reaching out to the world

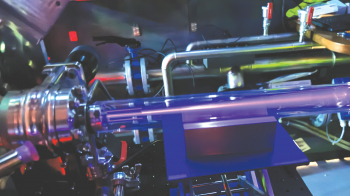

Workshops and hands-on activities have multiplied in recent years. Cloud-chamber building is one of the most popular, and is used by a growing number of institutes when they host students for a day. Created in 2005, the International Masterclasses programme brings another level of activity, offering guests the chance to analyse data from contemporary experiments with direct help from the physicists involved. Each year, more than 10,000 teachers and 15–19-year-old students have been given this opportunity. Initially organised in the EU time zone with a scientist at CERN, the programme now also runs in US and Japanese time zones. The range of analyses offered encompasses the four LHC experiments, Belle II, particle therapy, the Pierre Auger cosmic-ray detector and neutrino experiments in the US. During the pandemic, masterclasses were made available online, and the tools developed now help to reach people in countries and regions that do not yet have any high-energy physics institutes.

The large number of CERN visitors is proof of public interest in face-to-face interactions. But what about those who can’t come in person? What about teachers who want to inspire their students by inviting a scientist into their classrooms? Or institutes that would like to show a detector their teams have built and where the data come from? Pioneered by ATLAS in 2010, the LHC experiments virtual-visit programme breaks down geographical barriers. Thanks to a video conference tool, a scientist working on an experiment can walk audiences through underground installations or control rooms, the diversity of international-collaboration members offering a wide range of languages to let the public meet and engage with “one of theirs”. The most important part of the event is a lengthy Q&A session, which has allowed tens of thousands of children and adults to share the scientific experience.

Coming together

Organised by interactions.org, a network that groups the communications activities of the world’s particle-physics labs, Dark Matter Day offers a scientific twist to Halloween. Since 2017, more than 350 global, regional and local events have been held on and around 31 October. Institutions and individuals engage the public in discussions about what is known and what mysteries experiments are seeking to solve. International Cosmic Day, where students, teachers and scientists come together to talk and learn about cosmic rays, follows each November. Activities range from the construction of a detector to data analysis, and the coordination of such events is kept light, to let the primary actors – the scientists who proposed and built the 17 presently listed activities – be as creative and engaged as they are in everyday life. As with all community-driven outreach activities, that authenticity is hard to beat.