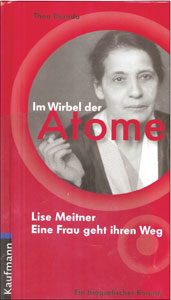

By Thea Derado, Kaufmann Verlag 2007. Hardback ISBN 9783780630599, €19.95.

Using letters, articles and biographies the author of this book paints a lively and private picture of the tragic life of Lise Meitner, which was thorny for two reasons: she was Jewish and a woman. Born in 1878 Meitner attended school in Vienna but could pass her maturity examination only after expensive private lessons. After studying in Vienna, she moved to Berlin in 1907, and for many years had to earn her living by giving private teaching lessons. Eventually she was accepted by the radiochemist Otto Hahn as a physicist collaborator at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin (but without pay), and so began a creative co-operation and a lifelong friendship. Since women were not allowed to enter the institute, Meitner had to do experiments in a wood workshop in the basement accessible from a side entrance.

Derado describes Meitner’s scientific achievements in an understandable way, particularly experiments leading to nuclear fission and the discovery of protactinium. The technical terms are explained in an appendix.

During her stay in Berlin, Meitner met all the celebrities in physics at the time, such as Max Planck, James Franck, Emil Fischer and Albert Einstein, whose characters are all described in a colurful fashion. She developed warm relations with Max von Laue, one of the few German physicists who had bravely withstood the Nazi regime. Apart from science, music played an important role in her life, and through music Meitner made friends with Planck’s family and happily sang Brahms’ songs with Hahn in the wood workshop.

During the First World War Meitner volunteered for the Austrian army as a radiologist. Working in a military hospital she learned the horrors of war. These experiences, and discussions with Hahn and Einstein led to some inner conflicts. During the persecution of the Jews by the Nazis, Meitner enjoyed a certain protection thanks to her Austrian passport, yet after the annexation of Austria it became impossible for her to leave Germany legally. Neglecting her colleagues’ warnings she hesitated too long, until in July 1938 she saved herself by escaping to Holland. Hahn gave her a diamond ring that he had inherited from his mother as a farewell present.

After a short stay in Holland Niels Bohr arranged for Meitner to stay at the Nobel Institute in Stockholm, which was directed by Manne Siegbahn, and finally in 1947 she obtained a research professorship at the Technical University in Stockholm. I was able to work with her there for a year and can confirm many of the episodes mentioned in the book. She was a graceful little person, with a combination of Austrian charm, Prussian orderliness and a sense of duty; she was also very kind and motherly.

Derado discusses, of course, why Meitner did not share the Nobel Prize with Hahn in 1944. Her merits were uncontested, and even after the publication of the Nobel Prize documents questions remain unanswered. It seems that being a woman had negative influences. However, numerous German and international honours and awards, as well as an overwhelming reception in the US, have compensated to a certain extent.

Meitner never married, but various family ties played an important role in her life. She was particularly attached to her nephew Otto Frisch, with whom she interpreted nuclear fission. She spent her last days with him in Cambridge, where she died in 1968.

In all, this book provides an historically accurate account, at the same time from a female perspective, of the turbulent life of one of the greatest scientists of the 20th century. It is worth reading, not only for those interested in history, but also perhaps as encouragement for young women scientists.

• This is an abridged version of a review originally published in German in Spektrum der Wissenschaft, March 2008.