By Ivar Giaever

World Scientific

At the end of his last semester studying mechanical engineering at the Norwegian Institute of Technology, Ivar Giaever gained a grade of 3.5 for a thesis on the efficiency of refrigeration machines – just a little better than the 4.0 needed to pass. The thesis had been hastily written as the machines worked badly, and he and his friend had had little time to collect their data. But they both scraped through and, as Giaever writes, “maybe sometimes life is a little bit fair after all?”.

It’s a reference to the opening words of his light-hearted autobiography: “Life is not fair, and I, for one, am happy about that.” The title sounds provocative, but

the book is a reflection on how life’s little twists and turns can have extremely important consequences.

Giaever calls this “luck” and admits that he has had more than his share of it – from relatively humble beginnings in Norway to a Nobel prize and beyond.

In many respects Giaever had been a “bad” student. Good at cards, billiards, chess – and drinking – he had little interest in mechanical engineering. He finished with a grade of 4.0 in both physics and mathematics; but had at least married Inger, his long-time sweetheart.

His first job was at the patent office in Oslo, but apartments were hard to find, so the couple decided to emigrate to Canada. A few twists led Giaever to General Electric (GE), where he had the chance to study again through the company’s “A, B and C” courses.

This second chance to learn proved pivotal. Seeing how the studies related to GE’s production of generators, motors and such like, made learning exciting, and Giaever graduated as the best student on the A course. But GE in Canada offered only the A course and, eager to learn more, he moved to GE’s Research Laboratory in Schenectady in the US.

There he completed the B and C courses, and also began studying for a master’s degree in physics at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI). He was to remain with GE for the next 30 years, after being offered a permanent job, even though he did not yet have a PhD.

As a fully-fledged member of the research lab, Giaever needed a project. John Fisher proposed that he look into quantum mechanical tunnelling between thin films, which Giaever went on to do with great success in 1959.

Then, during his studies at RPI, he learned about the new Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) theory of superconductivity, which predicted the appearance of a forbidden energy gap near the Fermi level when a metal becomes superconducting. Giaever realised that he could measure this gap using his tunnelling apparatus, and so provide crucial verification of the BCS theory. He also realised that tunnelling between two superconductors with different energy gaps would produce a negative resistance, and could allow for active devices such as amplifiers. He worried that if he talked about his work, others would realise this before he had done the relevant experiment.

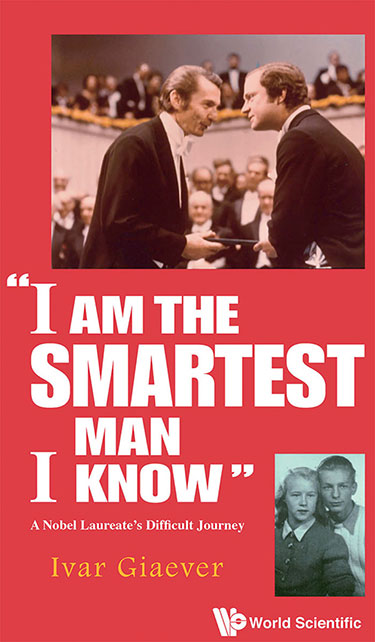

To his surprise nobody did, hence his comment to his family: “I am the smartest man I know!”. His children thought he was being big-headed, but in 1973 the whole family went with him to Stockholm when he was rewarded with a share of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1973 for his work on tunnelling in superconductors.

Giaever, of course, covers much more of his life story in this book. There is little technical detail, but a plethora of anecdotes that provide fascinating insight into a person who has made the most of his life.

Two impressions stand out: he is lucky to have found in Inger a partner with whom he has been able to share his long life; and he is lucky to have had a second chance to study and discover that he is smarter than many people thought.