The 2025 European Physical Society Conference on High Energy Physics (EPS-HEP), held in Marseille from 7 to 11 July, took centre stage in this pivotal year for high-energy physics as the community prepares to make critical decisions on the next flagship collider at CERN to enable major leaps at the high-precision and high-energy frontiers. The meeting showcased the remarkable creativity and innovation in both experiment and theory, driving progress across all scales of fundamental physics. It also highlighted the growing interplay between particle, nuclear, astroparticle physics and cosmology.

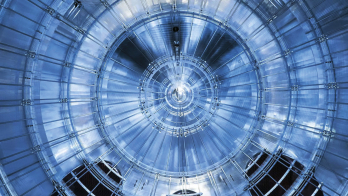

Advancing the field relies on the ability to design, build and operate increasingly complex instruments that push technological boundaries. This requires sustained investment from funding agencies, laboratories, universities and the broader community to support careers and recognise leadership in detectors, software and computing. Such support must extend across construction, commissioning and operation, and include strategic and basic R&D. The implementation of detector R&D (DRD) collaborations, as outlined in the 2021 ECFA roadmap, is an important step in this direction.

Physics thrives on precision, and a prime example this year came from the Muon g–2 collaboration at Fermilab, which released its final result combining all six data runs, achieving an impressive 127 parts-per-billion precision on the muon anomalous magnetic moment (CERN Courier July/August 2025 p7). The result agrees with the latest lattice–QCD predictions for the leading hadronic–vacuum-polarisation term, albeit within a four times larger theoretical uncertainty than the experimental one. Continued improvements to lattice QCD and to the traditional dispersion-relation method based on low-energy e+e– and τ data are expected in the coming years.

Runaway success

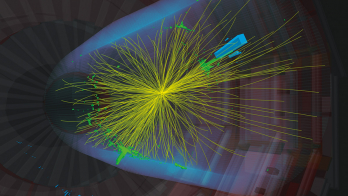

After the remarkable success of LHC Run 2, Run 3 has now surpassed it in delivered luminosity. Using the full available Run-2 and Run-3 datasets, ATLAS reported 3.4σ evidence for the rare Higgs decay to a muon pair, and a new result on the quantum-loop mediated decay into a Z boson and a photon, now more consistent with the Standard Model prediction than the earlier ATLAS and CMS Run-2 combination (see “Mapping rare Higgs-boson decays”). ATLAS also presented an updated study of Higgs pair production with decays into two b-quarks and two photons, whose sensitivity was increased beyond statistical gains thanks to improved reconstruction and analysis. CMS released a new Run-2 search for Higgs decays to charm quarks in events produced with a top-quark pair, reaching sensitivity comparable to the traditional weak-boson-associated production. Both collaborations also released new combinations of nearly all their Higgs analyses from Run 2, providing a wide set of measurements. While ATLAS sees overall agreement with predictions, CMS observes some non-significant tensions.

Advancing the field relies on the ability to design, build and operate increasingly complex instruments that push technological boundaries

A highlight in top-quark physics this year was the observation by CMS of an excess in top-pair production near threshold, confirmed at the conference by ATLAS (see “ATLAS confirms top–antitop excess”). The physics of the strong interaction predicts highly compact, colour-singlet, quasi-bound pseudoscalar top–antitop state effects arising from gluon exchange. Unlike bottomonium or charmonium, no proper bound state is formed due to the rapid weak decay of the top quark (see “Memories of quarkonia”). This “toponium” effect can be modelled with the use of non-relativistic QCD. Both experiments observed a cross section about 100 times smaller than for inclusive top-quark pair production. The subtle signal and complex threshold modelling make the analysis challenging, and warrant further theoretical and experimental investigation.

A major outcome of LHC Run 2 is the lack of compelling evidence for physics beyond the Standard Model. In Run 3, ATLAS and CMS continue their searches, aided by improved triggers, reconstruction and analysis techniques, as well as a dataset more than twice as large, enabling a more sensitive exploration of rare or suppressed signals. The experiments are also revisiting excesses seen in Run 2, for example, a CMS hint of a new resonance decaying into a Higgs and another scalar was not confirmed by a new ATLAS analysis including Run-3 data.

Hadron spectroscopy has seen a renaissance since Belle’s 2003 discovery of the exotic X(3872), with landmark advances at the LHC, particularly by LHCb. CMS recently reported three new four-charm-quark states decaying into J/ψ pairs between 6.6 and 7.1 GeV. Spin-parity analysis suggests they are tightly bound tetraquarks rather than loosely bound molecular states (CERN Courier November/December 2024 p33).

Rare observations

Flavour physics continues to test the Standard Model with high sensitivity. Belle-II and LHCb reported new CP violation measurements in the charm sector, confirming the expected small effects. LHCb observed, for the first time, CP violation in the baryon sector via Λb decays, a milestone in CP violation history. NA62 at CERN’s SPS achieved the first observation of the ultra-rare kaon decay K+ → π+νν with a branching ratio of 1.3 × 10–10, matching the Standard Model prediction. MEG-II at PSI set the most stringent limit to date on the lepton-flavour-violating decay μ → eγ, excluding branching fractions above 1.5 × 10–13. Both experiments continue data taking until 2026.

Heavy-ion collisions at the LHC provide a rich environment to study the quark–gluon plasma, a hot, dense state of deconfined quarks and gluons, forming a collective medium that flows as a relativistic fluid with an exceptionally low viscosity-to-entropy ratio. Flow in lead–lead collisions, quantified by Fourier harmonics of spatial momentum anisotropies, is well described by hydrodynamic models for light hadrons. Hadrons containing heavier charm and bottom quarks show weaker collectivity, likely due to longer thermalisation times, while baryons exhibit stronger flow than mesons due to quark coalescence. ALICE reported the first LHC measurement of charm–baryon flow, consistent with these effects.

Spin-parity analysis suggests the states are tightly bound tetraquarks

Neutrino physics has made major strides since oscillations were confirmed 27 years ago, with flavour mixing parameters now known to a few percent. Crucial questions still remain: are neutrinos their own antiparticles (Majorana fermions)? What is the mass ordering – normal or inverted? What is the absolute mass scale and how is it generated? Does CP violation occur? What are the properties of the right-handed neutrinos? These and other questions have wide-ranging implications for particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology.

Neutrinoless double-beta decay, if observed, would confirm that neutrinos are Majorana particles. Experiments using xenon and germanium are beginning to constrain the inverted mass ordering, which predicts higher decay rates. Recent combined data from the long-baseline experiments T2K and NOvA show no clear preference for either ordering, but exclude vanishing CP violation at over 3σ in the inverted scenario. The KM3NeT detector in the Mediterranean, with its ORCA and ARCA components, has delivered its first competitive oscillation results, and detected a striking ~220 PeV muon neutrino, possibly from a blazar (CERN Courier March/April 2025 p7). The next-generation large-scale neutrino experiments JUNO (China), Hyper-Kamiokande (Japan) and LBNF/DUNE (USA) are progressing in construction, with data-taking expected to begin in 2025, 2028 and 2031, respectively. LBNF/DUNE is best positioned to determine the neutrino mass ordering, while Hyper-Kamiokande will be the most sensitive to CP violation. All three will also search for proton decay, a possible messenger of grand unification.

There is compelling evidence for dark matter from gravitational effects across cosmic times and scales, as well as indications that it is of particle origin. Its possible forms span a vast mass range, up to the ~100 TeV unitarity limit for a thermal relic, and may involve a complex, structured “dark sector”. The wide complementarity among the search strategies gives the field a unifying character. Direct detection experiments looking for tiny, elastic nuclear recoils, such as XENONnT (Italy), LZ (USA) and PandaX-4T (China), have set world-leading constraints on weakly interacting massive particles. XENONnT and PandaX-4T have also reported first signals from boron-8 solar neutrinos, part of the so-called “neutrino fog” that will challenge future searches. Axions, introduced theoretically to suppress CP violation in strong interactions, could be viable dark-matter candidates. They would be produced in the early universe with enormous number density, behaving, on galactic scales, as a classical, nonrelativistic, coherently oscillating bosonic field, effectively equivalent to cold dark matter. Axions can be detected via their conversion into photons in strong magnetic fields. Experiments using microwave cavities have begun to probe the relevant μeV mass range of relic QCD axions, but the detection becomes harder at higher masses. New concepts, using dielectric disks or wire-based plasmonic resonance, are under development to overcome these challenges.

Cosmological constraints

Cosmology featured prominently at EPS-HEP, driven by new results from the analysis of DESI DR2 baryon acoustic oscillation (BAO) data, which include 14 million redshifts. Like the cosmic microwave background (CMB), BAO also provides a “standard ruler” to trace the universe’s expansion history – much like supernovae (SNe) do as standard candles. Cosmological surveys are typically interpreted within the ΛCDM model, a six-parameter framework that remarkably accounts for 13.8 billion years of cosmic evolution, from inflation and structure formation to today’s energy content, despite offering no insight into the nature of dark matter, dark energy or the inflationary mechanism. Recent BAO data, when combined with CMB and SNe surveys, show a preference for a form of dark energy that weakens over time. Tensions also persist in the Hubble expansion rate derived from early-universe (CMB and BAO) and late-universe (SN type-Ia) measurements (CERN Courier March/April 2025 p28). However, anchoring SN Ia distances in redshift remains challenging, and further work is needed before drawing firm conclusions.

Cosmological fits also constrain the sum of neutrino masses. The latest CMB and BAO-based results within ΛCDM appear inconsistent with the lower limit implied by oscillation data for inverted mass ordering. However, firm conclusions are premature, as the result may reflect limitations in ΛCDM itself. Upcoming surveys from the Euclid satellite and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory (LSST) are expected to significantly improve cosmological constraints.

Cristinel Diaconu and Thomas Strebler, chairs of the local organising committee, together with all committee members and many volunteers, succeeded in delivering a flawlessly organised and engaging conference in the beautiful setting of the Palais du Pharo overlooking Marseille’s old port. They closed the event with a memorial phrase of British cyclist Tom Simpson: “There is no mountain too high.”