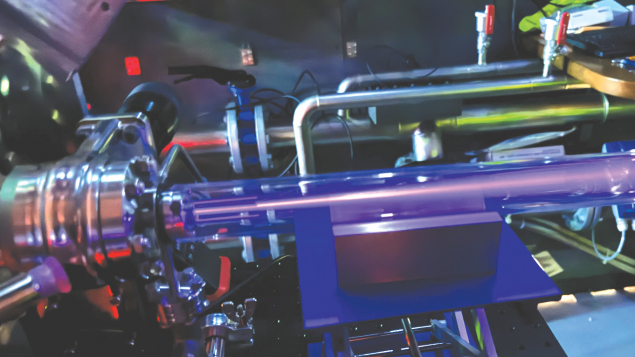

What better way to communicate accelerator physics to the public than using a functioning particle accelerator? From January, visitors to CERN’s Science Gateway were able to witness a beam of protons being accelerated and focused before their very eyes. Its designers believe it to be the first working proton accelerator to be exhibited in a museum.

“ELISA gives people who visit CERN a chance to really see how the LHC works,” says Science Gateway’s project leader Patrick Geeraert. “This gives visitors a unique experience: they can actually see a proton beam in real time. It then means they can begin to conceptualise the experiments we do at CERN.”

The model accelerator is inspired by a component of LINAC 4 – the first stage in the chain of accelerators used to prepare beams of protons for experiments at the LHC. Hydrogen is injected into a low-pressure chamber and ionised; a one-metre-long RF cavity accelerates the protons to 2 MeV, which then pass through a thin vacuum-sealed window. In dim light, the protons in the air ionise the gas molecules, producing visible light, allowing members of the public to see the beam’s progress before their very eyes (see “Accelerating education” figure).

ELISA – the Experimental Linac for Surface Analysis – will also be used to analyse the composition of cultural artefacts, geological samples and objects brought in by members of the public. This is an established application of low-energy proton accelerators: for example, a particle accelerator is hidden 15 m below the famous glass pyramids of the Louvre in Paris, though it is almost 40 m long and not freely accessible to the public.

“The proton-beam technique is very effective because it has higher sensitivity and lower backgrounds than electron beams,” explains applied physicist and lead designer Serge Mathot. “You can also perform the analysis in the ambient air, instead of in a vacuum, making it more flexible and better suited to fragile objects.”

For ELISA’s first experiment, researchers from the Australian Nuclear Science Technology Organisation and from Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum have proposed a joint research project about the optimisation of ELISA’s analysis of paint samples designed to mimic ancient cave art. The ultimate goal is to work towards a portable accelerator that can be taken to regions of the world that don’t have access to proton beams.