John Ellis looks at what CERN can offer scientists – and the wider society – in developing countries.

To paraphrase Tolstoy’s introduction to Anna Karenina, every developing country is developing in its own way. It is for each developing country to define its own needs and set its own agenda. So in this context, what is, or what should be, the relationship of CERN to developing countries? In what ways do they already benefit from the work at CERN, and how might they benefit from further collaboration?

CERN’s original raison d’être was to provide a vehicle for European integration and development, whilst also enabling smaller countries to participate in cutting-edge research, and to reduce the brain drain of young European scientists to the United States. Nowadays, CERN is internationally recognized for setting the standard of excellence in a very demanding field, and serves as a beacon of European scientific culture. CERN is open to qualified scientists from anywhere in the world, and beyond its 20 European member states currently has co-operation agreements with 30 countries. Prominent among these – beyond North America and Japan – are Brazil, China, India, Iran, Mexico, Morocco, Pakistan, Russia and South Africa, and more than 1000 people from these countries are listed in the database of scientists as using CERN for their experiments.

Experimental groups from developing nations are not asked to make large cash contributions to the construction of detectors, but rather to produce components. These are valued according to European prices, and if the developing countries can produce them more cheaply using local resources, then more power to their elbows. In Russia’s case, European and American funds were important in helping to convert military institutes into civilian work.

In addition to participating in experiments, some of these countries, notably Russia and India, have also contributed to the construction of accelerators at CERN. Russia and India are now making important contributions to the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) that is being constructed at CERN, and Pakistan has also offered to contribute. Again, CERN does not require these countries to pay any money towards the construction or operation of its accelerators. Indeed, CERN pays cash for the accelerator components that Russia and India provide, which these countries use to support their own scientific activities.

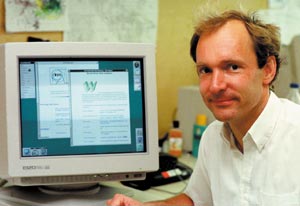

What, then, are the main benefits for developing countries in collaborating with CERN? It certainly provides them with a way to participate in research at the cutting edge, just as it always has for physicists from smaller European countries. In general, these users spend limited periods at CERN, preparing experiments, taking data and meeting other scientists. Thanks to the Internet, and to CERN’s World Wide Web in particular, particle physicists were the first to make remote collaboration commonplace, and this habit has spread to many other fields beyond the sciences. It is now relatively easy for scientists working on an experiment at CERN to maintain contact with their colleagues around the world, and they can even contribute to software development, data analysis and hardware construction from their home institute. The Web has enabled Indian experimentalists to access LEP data, and their theoretician colleagues to access the latest scientific papers from around the world, all while sitting at their home desks.

CERN is now also a leading player in European Grid computing initiatives. These will benefit many other scientific fields, for which applications are already being developed. Grid projects involve writing a great deal of software and middleware, which is split up into many individual work packages. CERN is keen to share the burden of preparing the Grid with developing countries. For example, several LHC Grid work packages have been offered to India, and other countries such as Iran and Pakistan have expressed an interest and would be welcome to join. In this way, such countries can become involved in developing the technology themselves, thus avoiding the negative psychological dependency on technological “hand outs” (as in the “cargo cults” in New Guinea after the Second World War).

The everyday acts of collaborating with colleagues in more developed nations exposes physicists from developing countries to the leading global standards in technology, research and education. Collaborating universities and research institutes are therefore provided with applicable standards of comparison and excellence, as well as training opportunities for their young scientists. These may be particularly valuable when educational values are threatened by a combination of increasing demand, insufficient resources and inefficiencies. One country where this is currently a concern is Pakistan. Its chief executive, Pervez Musharraf, has clearly stated his interest in encouraging scientific and technological development in Pakistan, and has exhorted other Islamic countries to do likewise.

How might such “ISO 9000” educational and academic standards be transferred to the wider society? Their value is limited if only a few élite institutions in each country benefit from the international contacts and they are not available throughout the educational system. This is essentially an issue for the internal organization within the country concerned, but CERN is happy to help out. The laboratory has archives of lectures in various formats available through the Web, offering resources for remote learning.

In India, for example, the benefits of collaborating with CERN increase to the extent that physicists from smaller universities outside the main research centres are brought into particle-physics research. In South Africa there are clear priorities in human development. However, a South African experimental group has joined the ALICE collaboration and CERN has welcomed a number of South Africans to its summer student programme, as well as a participant to its high-school teacher programme.

The information technologies that CERN has available should be of benefit to wider groups in developing societies. For example, could video archiving and data-distribution systems be used to disseminate public health information? This exciting idea was proposed to CERN by Rajan Gupta from the Los Alamos National Laboratory, and Manjit Dosanjh of CERN is now developing a pilot project in collaboration with the Ecole Superieure des Beaux Arts de Genève, supported by the foundation “Project HOPE” (see “Project HOPE” box).

This project will be demonstrated at the conference on The Role of Science in the Information Society (RSIS) that CERN is organizing in December 2003 as a side event of the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) (see “The Role of Science in the Information Society” below). Other sessions at this event will explore the potential of scientific information tools for aiding problems related to health, education, the environment, economic development and enabling technologies.

In 1946 Abdus Salam left his native Pakistan to pursue his scientific dreams in the West – dreams that were more than fulfilled with the award of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1979. However, his dream of bridging the gap between rich and poor through science and technology remained largely unfulfilled, as Riazuddin has described. If the world can develop its information society properly, a future Salam might not have to leave his – or her – country in order to do research in fundamental physics at the highest level. Moreover, a country’s participation in research at CERN might benefit not only academics and students, but also the wider society at large.

The Role of Science in the Information Society

On 10-12 December 2003, the first phase of the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) will take place in Geneva. The aim is to bring together key stakeholders to discuss how best to use new information technologies, such as the Internet, for the benefit of all. The International Telecommunications Union, under the patronage of UN secretary-general Kofi Annan, is organizing WSIS, and the second phase will take place in Tunis in November 2005.

The “information society” was made possible by scientific advances, and many of its enabling technologies were developed to further scientific research and collaboration. For example, the World Wide Web was invented at CERN to enable scientists from different countries to work together. It has gone on to help break down barriers around the world and democratize the flow of information.

For these reasons, science has a vital role to play at WSIS. Four of the world’s leading scientific organizations: CERN, the International Council for Science (ICSU), the Third World Academy of Science (TWAS) and UNESCO, have teamed up to organize a major conference on The Role of Science in the Information Society (RSIS), as a side event to WSIS. The conference will take advantage of CERN’s location close to Geneva to play a full role at the Summit.

Through an examination of how science provides the basis for today’s information society, and of the continuing role for science, the conference will provide a model for the technological underpinning of the information society of tomorrow. Parallel sessions will examine science’s future contributions to information and communication issues in the areas of education, healthcare, environmental stewardship, economic development and enabling technologies, and the conference’s conclusions will be discussed at the UNESCO round table on science at the Summit itself.

ICSU, TWAS and UNESCO have a long tradition of scientific, political and cultural collaboration across boundaries. CERN produces knowledge that is freely available for the benefit of science and society as a whole – the World Wide Web was made freely available to the global community and revolutionized the world’s communications landscape. Working together, these organizations are providing a meeting place for scientists of all disciplines, policy makers and stakeholders to share and form their vision of the developing information society.

The RSIS conference will take place on 8-9 December. Its conclusions will feed in to the UNESCO round table at WSIS, and it will set goals and deliverables that will be reported on at Tunis in 2005. The scientific community’s commitment is long-term.

Participation at the RSIS conference will be by invitation and is limited to around 400. However, anyone who feels they have something to contribute to the debate can do so via a series of on-line forums that are accessible through the conference website. These forums will have the same themes as the parallel sessions at the conference and will be moderated by the session convenors. Their conclusions will provide valuable input to the conference itself, and as an added incentive, CERN is offering up to 10 expenses-paid invitations to the conference for those making the most valuable on-line forum contributions.