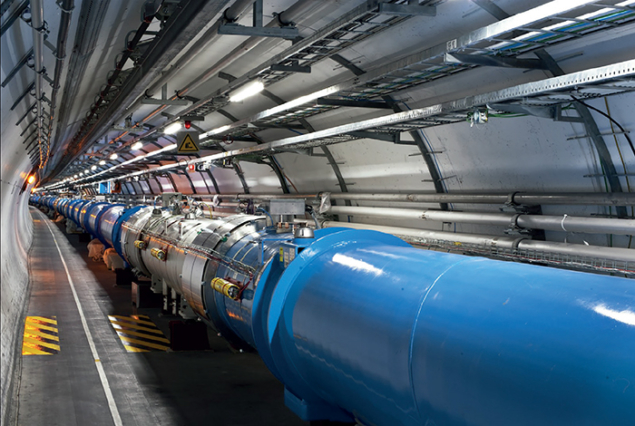

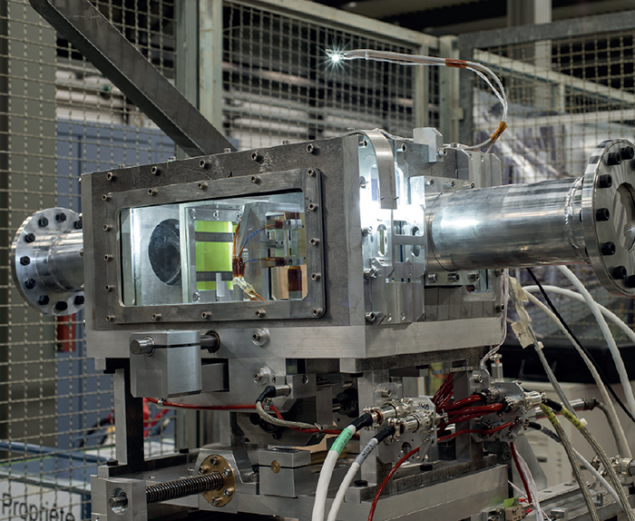

Image credit: CERN-PHOTO-201407-151-3.

To maintain scientific progress and exploit the full capacity of the LHC, the collider will need to operate at higher luminosity. Like shining a brighter light on an object, this will allow more accurate measurements of new particles, the observation of rarer processes, and increase the discovery reach with rare events at the high-energy frontier. The High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC) project began in 2011 under the framework of a European Union (EU) grant as a conceptual study, with the aim to increase its luminosity by a factor of 5–10 beyond the original design value and provide 3000 fb–1 in 10 to 12 years.

Two years later, CERN Council recognized the project as the top priority for CERN and for Europe (CERN Courier July/August 2013 p9), and then confirmed its priority status in CERN’s scientific and financial programme in 2014 by approving the laboratory’s medium-term plan for 2014–2019. Since this approval, new activities have started up to deliver key technologies that are needed for the upgrade. The latest results and recommendations by the various reviews that took place in 2014 were the main topics for discussion at the 4th Joint HiLumi LHC/LARP Annual Meeting, which was hosted by KEK in Tsukuba in November.

The latest updates

The event began with plenary sessions where members of the collaboration management – from CERN, KEK, the US LHC Accelerator Research Program (LARP) and the US Department of Energy – gave invited talks. The first plenary session closed with an update on the status of HL-LHC by the project leader, CERN’s Lucio Rossi, who also officially announced the new HL-LHC timeline. The plenary was followed by expert talks on residual dose-rate studies, layout and integration, optics and operation modes and progress on cooling, quench and assembly (together known as QXF). Akira Yamamoto of KEK presented the important results and recommendations of the recent superconducting cable review.

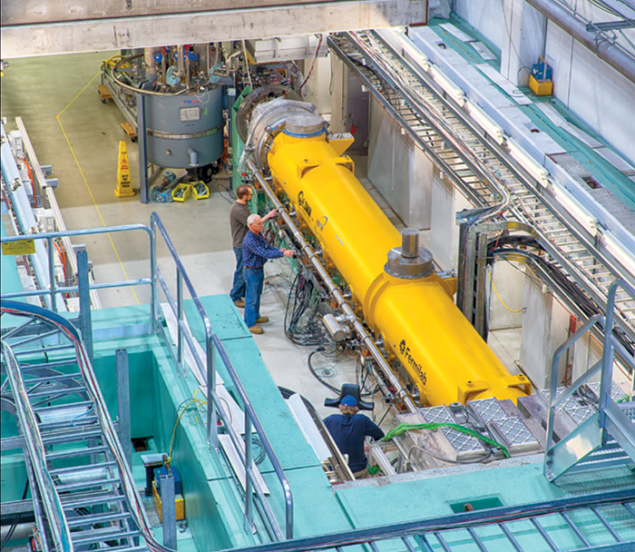

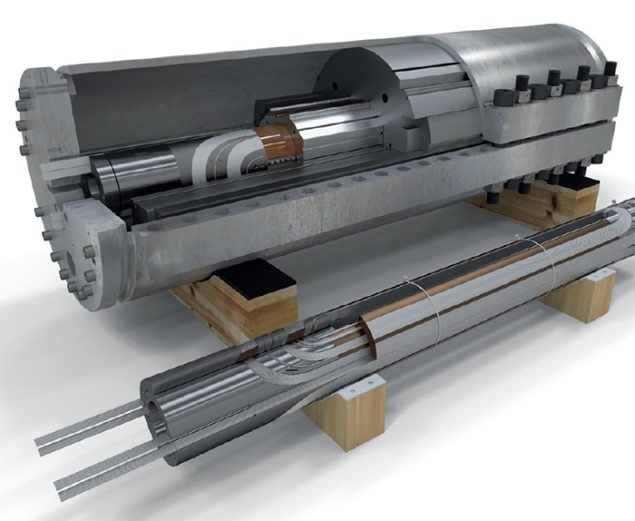

Image credit: KEK.

There were invited talks on the LHC Injectors Upgrade (LIU) by project leader Malika Meddahi from CERN, and on the outcomes of the 2nd ECFA HL-LHC Experiments Workshop held in October – an indication of the close collaboration with the experimentalists. One of the highlights of the plenaries was the status update on the Preliminary Design Report – the main deliverable of the project, which is to be published soon. There were three days of parallel sessions reviewing the progress in design and R&D in the various work packages – named in terms of activities – both with and without EU funding.

Refined optics and layout of the high-luminosity insertions have been provided by the activity on accelerator physics and performance, in collaboration with the other work packages. This new baseline takes into account the updated design of the magnets (in particular those of the matching section), the results of the energy deposition and collimation studies, and the constraints resulting from the integration of the components in the tunnel. The work towards the definition of the specifications for the magnets and their field quality has progressed, with an emphasis on the matching section for which a first iteration based on the requirements resulting from studies of beam dynamics has been completed. The outcomes include an updated impedance model of the LHC and a preliminary estimate of the resulting intensity limits and beam–beam effects. The studies confirmed the need for low-impedance collimators. In addition, an updated set of beam parameters consistent through all of the injectors and the LHC has been defined in collaboration with the LIU team.

Progress with magnets

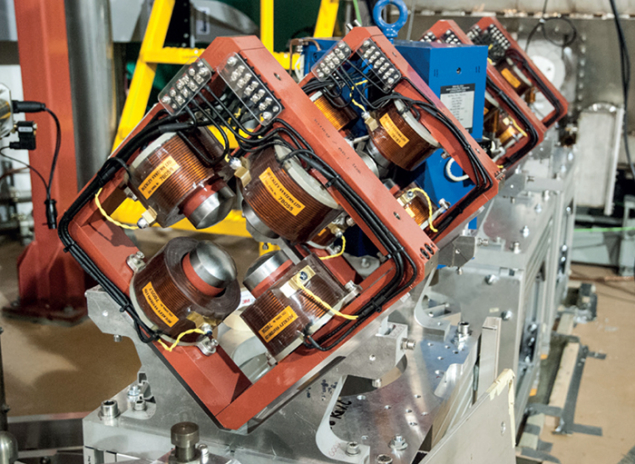

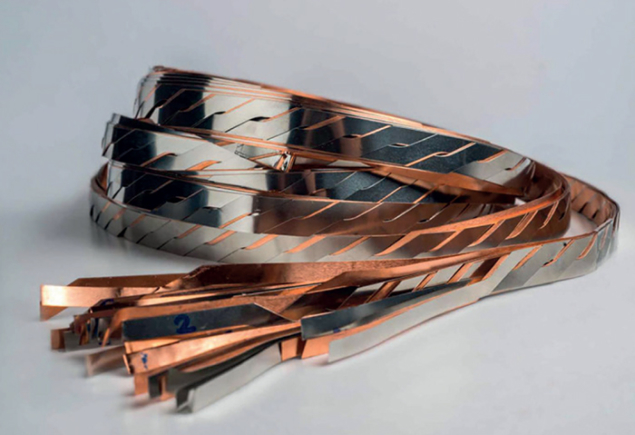

Image credit: CERN.

The main efforts of the activity on magnets for insertion regions (IRs) in the past 18 months focused on the exploration of different options for the layout of the interaction region. The main parameters of the magnet lattice, such as operational field/gradients, apertures, lengths and magnet technology, have been chosen as a result of the worldwide collaboration, including US LARP and KEK. A baseline for the layout of the new interaction region is one of the main results of this work. There is now a coherent layout, agreed with the beam dynamics, energy deposition, cooling and vacuum teams, covering the whole interaction region.

The engineering design of most of the IR magnets has now started and the first hardware tests are expected in 2015. There was also good news from the quench-protection side, which can meet all of the key requirements based on the results from tests performed on the magnets. In addition, there is a solution for cooling the inner triplet (IT) quadrupoles and the separation dipole, D1. It relies on two heat exchangers for the IT quadrupole/orbit correctors assembly, with a separate system for the D1 dipole and the high-order corrector magnets. Besides these results, considerable effort was devoted to selecting the technologies and the design for the other magnets required in the lattice, namely the orbit correctors, the high-order correctors and the recombination dipole, D2.

Crabs and collimators

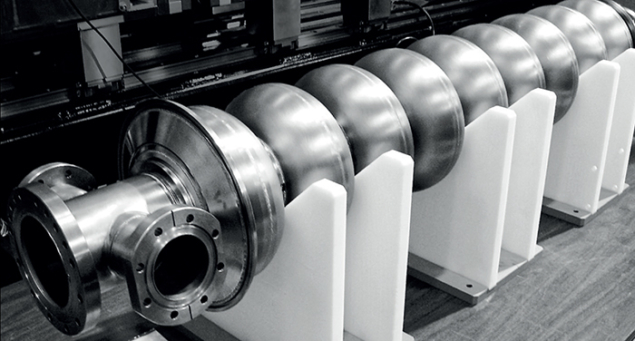

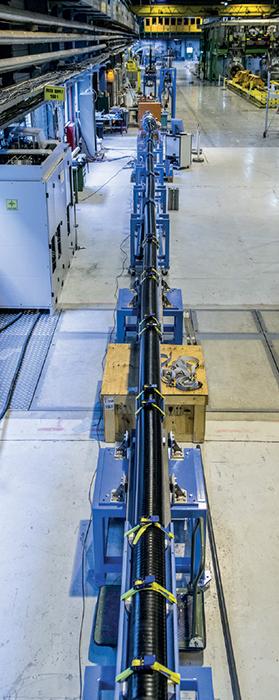

Image credit: CERN.

The crab-cavities activity delivered designs for three prototype crab cavities, based on four-rod, RF-dipole (RFD) and double quarter-wave (DQW) structures. They were all tested successfully against the design gradient with higher-than-expected surface resistance. Further design improvements to the initial prototypes were made to comply with the strict requirements for higher-order-mode damping, while maintaining the deflecting field performance. There was significant progress on the engineering design of the dressed cavities and the two-cavity cryomodule conceptual design for tests at CERN’s Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS).

Full design studies, including thermal and mechanical analysis, were done for all three cavities, culminating in a major international design review where the three designs were assessed by a panel of independent leading superconducting RF experts. As an outcome of this review, the activity will focus the design effort for the SPS beam tests on the RFD and DQW cavities, with development of the 4-rod cavity continuing at a lower priority and not foreseen for the SPS tests. A key milestone – to freeze the cavity designs and interfaces – has also been met. In addition, a detailed road map to follow the fabrication and installation in the SPS has been prepared to meet the deadline of the extended year-end technical stop of 2016–2017.

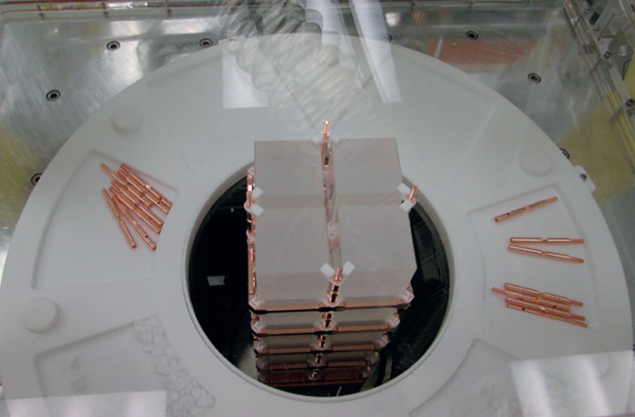

Image credit: CERN.

The wrap-up talk on the IR-collimation activity also reviewed the work of related non-EU-funded work packages, namely machine protection (WP7), energy deposition and absorber co-ordination (WP10), and beam transfer and kickers (WP14). The activity has reached several significant milestones, following the recommendations of the collimation-project external review, which took place in spring 2013. Highlights include important progress towards the finalization of the layouts for the IR collimation. A solid baseline solution has been proposed for the two most challenging cleaning requirements: proton losses around the betatron-cleaning insertion and losses from ion collisions. The solution is based on new collimators – the target collimator long dispersion suppressor, or TCLD – to be integrated into the cold dispersion suppressors. Thanks to the use of shorter 11 T dipoles that will replace the existing 15-m-long dipoles, there will be sufficient space for the installation of warm collimators between two cold magnets. This collimation solution is elegant and modular because it can be applied, in principle, at any “old” dipole location. As one of the most challenging and urgent upgrades for the high-luminosity era, solid baselines for the collimation upgrade in the dispersion suppressors around IR7 and IR2 were also defined. In addition, simulations have continued for advanced collimation layouts in the matching sections of IR1 and IR5, improving significantly the cleaning of “debris” from collisions downstream around the high-luminosity experiments.

Cold powering

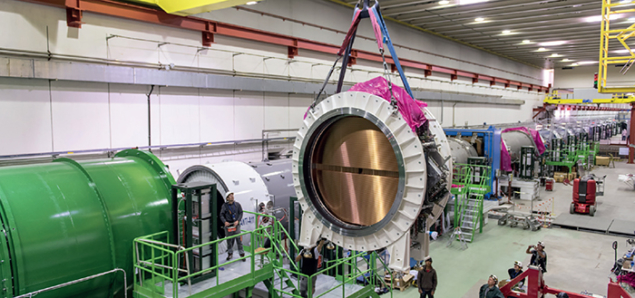

Image credit: CERN.

The cold-powering activity has seen the world-record current of 20 kA at 24 K in an electrical transmission line consisting of two 20-m-long MgB2 superconducting cables. Another achievement was with the novel design of the part of the cold-powering system that transfers the current from room temperature to the superconducting link. Following further elaboration, this was adopted as the baseline. The idea is that high-temperature superconducting (HTS) current-leads will be modular components that are connected via a flexible HTS cable to a compact cryostat, where the electrical joints between the HTS and MgB2 parts of the superconducting link are made. Simulation studies were also made to evaluate the electromagnetic and thermal behaviour of the MgB2 cables contained in the cold mass of the superconducting link, under static and transient conditions.

Image credit: Don Mitchell/Fermilab.

The final configuration has tens of high-current cables packed in a compact envelope to transfer a total current of about 150 kA feeding different magnet circuits. Cryogenic-flow schemes were also elaborated for the cold-powering systems at points 7, 1 and 5 on the LHC. An experimental study performed in the 20-m-long superconducting line at CERN was launched to understand quench propagation in the MgB2 superconducting cables operated in helium gas. In addition, integration studies of the cold-powering systems in the LHC were also done, with priority given to the system at point 7.

The meeting also covered updates on other topics such as machine protection, cryogenics, vacuum and beam instrumentation. Delicate arbitration took place between the needs of crab-cavity tests in the SPS at long straight section 4 and the requirements for the continuing study and tests of electron-cloud mitigation of those working on vacuum aspects (see Old machine to validate new technology below).

Summaries of the EU-funded work packages closed the meeting, showing “excellent technical progress thanks to the hard and smart work of many, including senior and junior”, as project leader Rossi concluded in his wrap-up talk.

Upcoming meetings will be the LARP/HiLumi LHC meeting on 11–13 May at Fermilab and the final FP7 HiLumi LHC/LARP collaboration meeting on 26–30 October at CERN. As a contribution to the UNESCO International Year of Light, special events celebrating this occasion will be organized by HL-LHC throughout the year – see cern.ch/go/light. (See also Viewpoint )

Old machine to validate new technology

Crab cavities have never been tested on hadron beams. So for the recently selected HL-LHC crab cavities (RFD and DQW, see main text), tests in the SPS beam are considered to be crucial. The goals are to validate the cavities with beam in terms of, for example, electric field, ramping, RF controls and impedance, and to study other parameters such as cavity transparency, RF noise, emittance growth and nonlinearities.

Long straight section 4 (LSS4) of the SPS already has a cold section, which was set up for the cold-bore experiment (COLDEX). Originally designed to measure synchrotron-radiation-induced gas release, COLDEX has become a key tool for evaluating electron-cloud effects. It mimics the cold bore and beam screen of the LHC for electron-cloud studies. Installed in the bypass line of the beam pipe, COLDEX is assembled on a moving table so that beam can pass either through the experiment during machine development runs or through the standard SPS beam pipe during normal operation. It has been running again since the SPS started up again last year after the first long shutdown, providing key information on new materials and technology to reduce or suppress severe electron-cloud effects that would otherwise be detrimental to LHC beams with 25 ns bunch spacing – as planned for Run 2.

Naturally, SPS LSS4 would be the right place to put the crab-cavity prototypes for the beam test. The goal was originally to install them during the extended year-end technical stop of 2016–2017, to validate the cavities in 2017, the year in which series construction must be launched. However, installing the cavities together with their powering and cryogenic infrastructure in an access time of 11–12 weeks is a real challenge. So at the meeting in Tsukuba, the idea of bringing forward part of the installation to 2015–2016 was discussed. However, in view of the severe electron-cloud effects that were computed in 2014 for LHC beam at high intensity, and the consequent need for a longer and deeper study to validate various solutions, COLDEX needs to run beyond 2015.

So what other options are there for testing the crab cavities? A preliminary look at possible locations for an additional cold section in the SPS led to LSS5. This would result in having two permanent “super” facilities to test equipment with proton beams. The hope is that these facilities would not only be available for testing crab cavities for the HL-LHC project, but would also provide a world facility for testing superconducting RF-accelerating structures in intense, high-energy proton beams. With the installation of adequate cryogenics and power infrastructure, a facility in LSS5 could further evolve and possibly also allow tests of beam damage and other beam effects for future superconducting magnets, for example for the Future Circular Collider study (CERN Courier April 2014 p16). This new idea raises many questions, but the experts are confident that these can be solved with suitable design and imagination.