All image credits: ESO.

On 5 October 1962, five nations signed the convention that founded the European Southern Observatory (ESO). Belgium, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden where soon followed by Denmark. They were later joined by Switzerland, Italy, Portugal, the UK, Finland, Spain, the Czech Republic and, most recently, Austria in 2009. Brazil, whose membership is pending ratification, will be the 15th member state and the first from outside Europe. The organization’s main mission, laid down in the convention signed in 1962, is to provide state-of-the-art research facilities to astronomers and astrophysicists, allowing them to conduct front-line science in the best conditions. With headquarters in Garching near Munich, ESO operates three observing sites high in the Atacama Desert region of Chile, which are home to a world-leading collection of observing facilities.

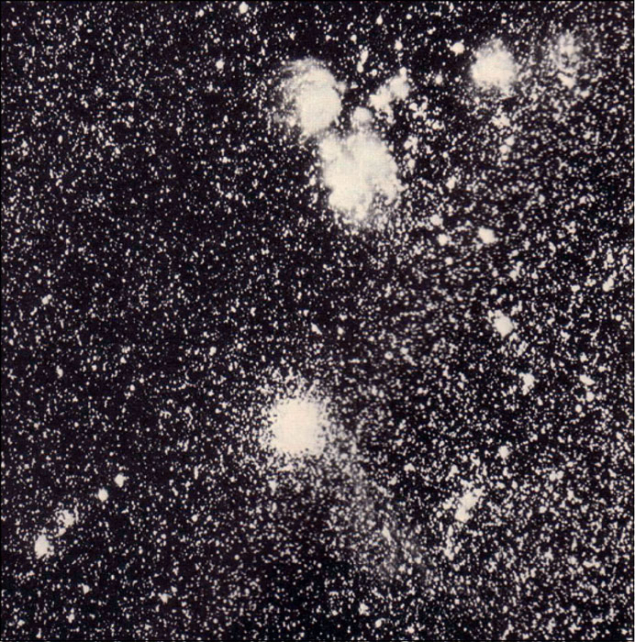

ESO’s ruling body is its council, which delegates day-to-day responsibility to the executive under the director-general, while other governing bodies of ESO include the Finance Committee and the Committee of Council. If this sounds familiar, it is probably because the origins of ESO bear more than a passing resemblance to those of CERN. The founding of ESO has its roots in a statement signed on 26 January 1954 by leading astronomers from six countries – the five nations that would later sign the ESO convention, plus the UK (which was to go in a different direction and join ESO only in 2002). The statement pointed to the lack of coverage of the skies of the southern hemisphere – which include interesting regions such as the Magellanic Clouds – by powerful telescopes at that time. It went on to put the case that although no one country had sufficient resources for such a project, it could be possible through international collaboration. Finally, it recommended the establishment of a joint observatory in South Africa that would house a 3 m telescope and a 1.2 m Schmidt telescope with a wide field of view, which would be valuable for surveys. These instruments would complement the 5 m Hale Telescope and the 1.2 m Schmidt that had been observing the skies of the northern hemisphere from the Palomar Observatory in California since 1948.

The idea for a joint European effort had originated the previous spring, when the pioneering Dutch astronomer, Jan Oort, invited Walter Baade, a renowned German working at the Mt Wilson and Palomar Observatories, to stay at Leiden for a couple of months. Oort mobilized a group of leading European astronomers for a meeting with the influential visitor on 21 June 1953, where Baade proposed capitalizing on existing designs for a 3 m telescope being built for the Lick Observatory in California and for the Schmidt telescope at Palomar. Also present at the meeting was Jan Bannier, director of the Dutch national science foundation and president of the provisional CERN Council.

The ESO convention

In November 1954, Bannier and Gösta Funke, director of the Swedish National Research Council and a member of the newly established formal CERN Council, drew up the first draft of a convention for ESO, with key similarities to the CERN convention. ESO would have a council with two delegates (at least one an astronomer) from each member state; each country would have an equal vote; financial contributions would be in proportion to national income up to a fixed limit.

Further progress was slow because the project’s supporters grappled with financial and political difficulties in their countries. Important impetus came with Oort’s successful application in 1959 for a grant from the Ford Foundation in the US for a $1 million – a fifth of the estimated cost at the time – on condition that at least four of the five potential members sign the convention. It took another three years for further issues to be resolved and for the convention to be signed on 5 October 1962, in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Paris. Even then, it was only in early 1964 that real work could begin (and the grant from the Ford Foundation released) when France became the fourth country to ratify the convention, after the Netherlands, Sweden and the German Federal Republic.

The original idea had been to locate the observatory in South Africa and over the period 1953–1963 searches for suitable places were followed by systematic tests at three sites in the Karoo region. However, in 1959 astronomers in the US began to explore the possibilities in the Chilean Andes, through the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA). It soon became clear that the Andes might offer better climatic conditions than South Africa for astronomy and in November 1962 two members of ESO’s site-testing team went to Chile. Their findings indicated a general superiority, in particular longer spells of clear weather and smaller temperature differences during the night (owing, in fact, to the higher altitude).

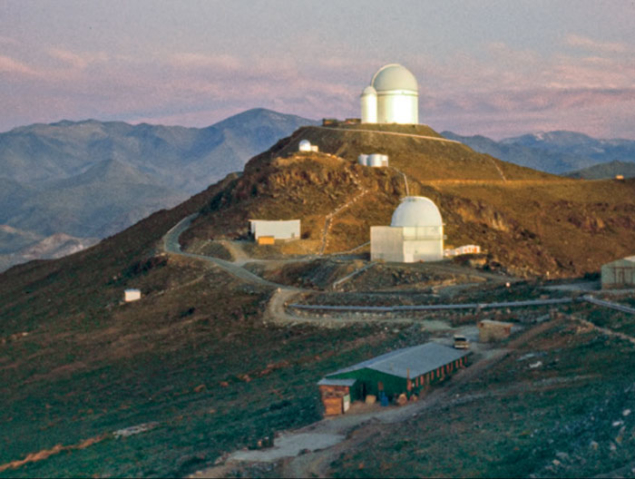

So, in June 1963 Otto Heckmann, the embryonic organization’s provisional director-general, and others including Oort went to Chile to meet members of AURA and see the mountains chosen by the Americans. Although the ESO convention had still to be ratified by the requisite four countries, in November the ESO Committee opted unanimously for the Andes, a decision that the formal ESO Council approved at its first meeting in 1964. Later that year, ESO decided on a site that was independent of the Americans – a mountaintop at 2400 m that Heckmann proposed naming La Silla (the saddle).

Image credit: Seggewiss/ESO.

ESO went on to develop La Silla, first installing a number of intermediate-size telescopes that had been foreseen in the convention, as well as some smaller national telescopes. The official inauguration, by the president of the Republic of Chile, Eduardo Frei Montalva, took place on 25 March 1969.

In the meantime, there was mounting concern about the slow progress on the larger telescopes described in the ESO convention and in March 1969 a working group was set up to advise the ESO Council on this and various administrative matters. In particular, it was to look into budget procedures and the project for the 3.6 m telescope. (The proposed size had grown after experience in the US had shown that the observer’s cage for a 3 m instrument raised problems for larger astronomers.) The working group was chaired by Funke and both he and Augustin Alline, the French government ESO Council delegate, were members of CERN Council. Their recommendations led to the introduction at ESO of the “Bannier process”, which had been established at CERN for budgetary matters; and at Alline’s suggestion, ESO also followed CERN’s example in setting up a Committee of Council, whose informal meetings of fewer people could iron out potential difficulties between meetings of Council.

It was at the meeting of CERN’s Committee of Council in November 1969 that CERN’s director-general, Bernard Gregory, reported on discussions with his counterpart at ESO about a possible collaboration between the two organizations – in essence, a rescue plan for the 3.6 m telescope. The project was similar in size and complexity to that of a large bubble chamber and there was also a strong feeling that particle physicists and astronomers could benefit from closer contact. The committee gave Gregory the go-ahead to report to the meeting of CERN Council in December, which in turn authorized him to continue the discussions with ESO. At the meeting, Bannier, who was currently president of the ESO Council, pointed out that with its greater experience in building large-scale apparatus and in dealing with industry CERN would bring valuable expertise to advance the 3.6 m project.

Image credit: ESO.

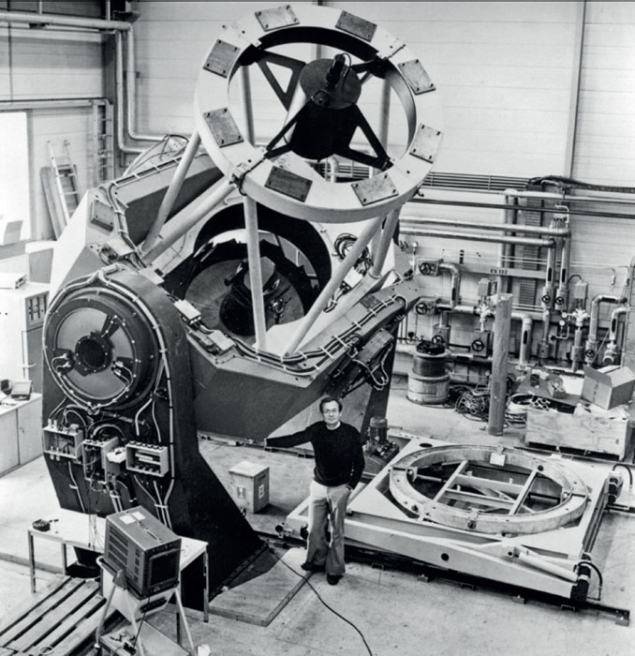

By June 1970, a draft co-operation agreement had been drawn up that foresaw the setting up of ESO’s Telescope Project Division at CERN. CERN would provide administrative, technical and professional services – the latter covering the project management as well as technical and scientific advice. This would be at no cost to CERN because all would be financed by ESO and no additional staff at CERN would be required. The June council meetings at ESO and CERN consented to collaboration between the two organizations and on 16 September the agreement was signed by Gregory and Adriaan Blaauw, ESO’s director-general. Within six months, the nucleus of the Telescope Project (TP) Division had formed at CERN. Led by ESO’s Svend Laustsen, it included his small technical group. The division then grew to comprise some 40 astronomers, engineers and technicians, all involved in the final design, construction and testing of the 3.6 m telescope, while benefiting from CERN’s experience in engineering and the administrative aspects of implementing a large project.

The members of TP interacted mainly with CERN’s Proton Synchrotron Department (particularly Wolfgang Richter and the department head, Kees Zilverschoon), the Technical Services and Building Division (Henri Laporte and E Leroy) and the Data Handling Division (Detmar Wiskott), while the placing of contracts involved working with the Finance Division. The first two years focused on completing the design of the telescope and the building to house it, with a first design report issued in February 1971. A year later, the group was awarding contracts related to the construction of the telescope, the building and a computer system, both to steer the telescope and for data-acquisition and some online analysis.

Further developments

Image credit: H H Heyer/ ESO.

November 1972 saw another development at CERN, with the inauguration of the ESO Sky Atlas Laboratory. To match the atlas of the northern sky made by the 1.2 m Schmidt telescope at Mt Palomar, ESO and the UK were pooling the resources of ESO’s 1 m Schmidt in Chile and the UK’s 1.2 Schmidt in Australia. A copy of each of the glass plates recorded in Chile was sent to the lab at CERN for further copying onto film. After a first rapid survey, ESO’s Schmidt telescope went on to cover red wavelengths in detail, the UK’s instrument covering blue. The Sky Atlas Lab was involved in producing 200 copies of the complete atlas, the full view totalling 200 m2 of film. One highlight of this work was the discovery of a new comet on 5 November 1975, named after its discoverer, the lab’s head, Danish astronomer Richard West.

In April 1975, the 3.6 m telescope was ready for testing in Europe. One innovation concerned the use of a fully automated control system, which involved some 120 individual computer-controlled motors for steering. The 18 m tall structure was assembled in a hall with a specially constructed pit to accommodate it at the Société Creusot-Loire at St Chamond. There, a van from CERN packed with electronic control-circuitry tested out the control system, determining the optimum configuration for driving the telescope’s two orientation axes. With testing complete, the telescope was dismantled and packed up for its journey to Chile, where it would be fitted with its giant mirror. The mirror blank had been ordered from Corning in the US as early as 1965 but a number of problems meant that its final processing to achieve a surface accuracy of 0.06 μm was not completed by the Recherches et études d’optique et de sciences connexes (REOSC), near Paris, until early 1972.

A year after it arrived in Chile, the telescope finally saw its “first light” on the night of 7–8 November 1976. The links with CERN were not quite over, however. A smaller 1.4 m instrument – the Coudé Auxiliary telescope (CAT) – was later designed by the TP team at CERN. Manufactured mainly by industry, it was assembled in CERN in early 1979 before going to Chile, where it fed the 3.6 m Coudé Echelle Spectrometer through a light tunnel. Fully computer controlled, the CAT was used for many different astronomical observations, including measuring the ages of ancient stars. The 3.6 m itself has since gone on to be highly productive, most recently with the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS), the world’s foremost hunter of planets beyond the solar system.

Writing in ESO’s journal, The Messenger, in 1981, Charles Fehrenbach, the director of the Haute Provence Observatory, who was involved with ESO for many of the early years, stated: “There is no doubt in my mind that it was the installation in Geneva which saved our organization.” The strong links with CERN certainly helped to set ESO on its way and the older organization can now look on with pleasure at its younger sibling’s many achievements.