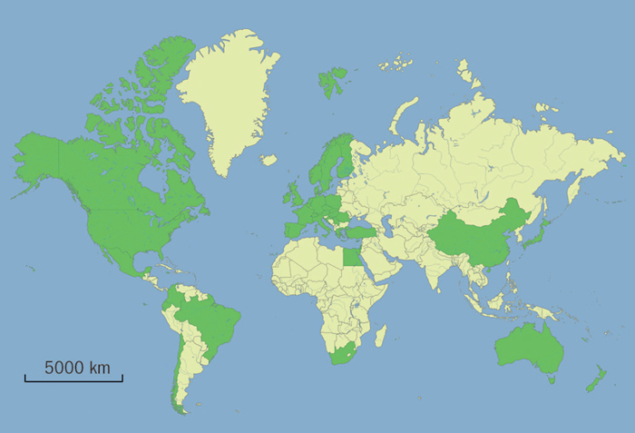

The International Masterclasses (IMCs) began in 2005 as an initiative of what was then the European Particle Physics Outreach Group (EPPOG). Since then, EPPOG has become the International Particle Physics Outreach Group (IPPOG), and the masterclasses have grown steadily beyond a group of IPPOG member countries. This year, the 10th edition of the IMCs included 200 institutions in 41 countries worldwide. Several of the initiatives have attracted new partners, including some from the Middle East and Latin America, enabling IMCs to be held in diverse locations – from Israel and Palestine to South Africa, and from New Zealand to Ecuador – in addition to the many sites in Europe and North America. Now, well into the LHC era, the masterclasses use fresh data from the world’s biggest particle accelerator, as collected by the four big experiments.

All of the LHC collaborations involved acknowledge the potential – and the success – of educational programmes that bring important discoveries at the LHC to high-school students by providing large samples of the most recent data. For example, 10% of the 8-TeV ATLAS “discovery” data are available for students to search for a Higgs boson; CMS approved 13 Higgs candidates in the mass region of interest, which are mixed with a more abundant sample of W and Z events, for “treasure hunt” activities; ALICE data allow students to study the relative production of strange particles, which could be a tell-tale signal of quark–gluon plasma production; LHCb teaches students how to measure the lifetime of the D meson; and particles containing b and c quarks are studied extensively to shed light on the mystery of antimatter in the universe.

Students quickly master real event-display programmes

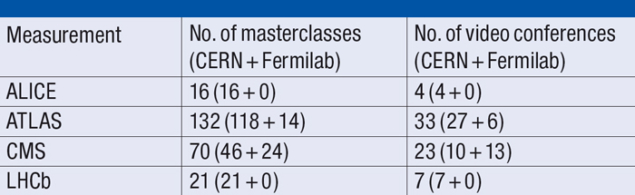

Students quickly master real event-display programmes – such as iSpy-online, Hypatia and Minerva – software tools and analysis methods. First, they practice particle identification by exploiting the characteristic signals left by particles in various detector elements, where electrons, muons, photons and jets are recognizable. They go on to select and categorize events, and then proceed with measurements. Typically, two students analyse 50–100 events, before joining peers to combine and discuss data with the tutors at their local IMC institution. Then they join students at several other locations to combine and discuss all of the data from that day in a video conference from CERN or Fermilab (see table 1).

The IMCs make five measurements available. Typically, a local institution selects one that their physicists have deep knowledge of, guaranteeing that experts are available to talk to the students about what they know best.

The ATLAS Z-path measurement relies on invariant mass for particle identification. It is first applied to measure the mass and width of the Z boson, and of the J/ψ and ϒ mesons. These parameters are all inferred from the decay products – pairs of e+e– or μ+μ– leptons. When a hypothetical new heavy gauge boson, Z´, is mixed with the data, the simulated signal shows up in the dilepton mass distribution. The students apply the same technique to di-photons and pairs of dileptons to search for decays of a Higgs boson to γγ and ZZ*, leading to a four-lepton final state.

The ATLAS W-path deals with the structure of the proton and the search for a Higgs boson. Students look for a W-boson decaying into a charged lepton and a neutrino (missing energy), and build the charge ratio NW+/NW–. The simple view of a proton structure of uud quarks leads to a naive approximation of NW+/NW– = 2. The presence of sea quarks and gluons complicates the picture, bringing the ratio down to around 1.5, compatible with the measurements by ATLAS and CMS. The next challenge is to study events containing W+W– pairs, which are characterized by two oppositely charged leptons and neutrinos. Decays of a Higgs boson to W+W– would enhance the distribution of the azimuthal angle between the charged leptons at low values.

The CMS measurement is called “WZH” for the W, Z, and Higgs bosons. Based on the signatures of leptonic decays, students determine whether each event is a W candidate, a Z candidate, a Higgs candidate, or background. For W bosons, they use the curvature of the single measurable lepton track to decide if it is a W+ or W– and so derive the charge ratio of W-boson production. They can also characterize events as having a muon or an electron to measure the electron-to-muon ratio. For Z and Higgs candidates, students put the invariant masses of lepton and dilepton pairs, respectively, in a mass plot. They discover the Z and Higgs peaks, including a few other resonances they might not have expected.

ALICE’s ROOT-based event-display software enables students to reconstruct strange particles (Ks, Λ, Λ) decaying to ππ and pπ. As a second step, they analyse large event samples from lead collisions in different regions of centrality, and normalize to the mean number of nucleons participating in the collision for each centrality region. Data from proton collisions and from lead-ion collisions lead to a measurement of the relative production of strangeness, which the students compare with theoretical predictions.

All of these educational packages are tuned and expanded to follow the LHC’s “heartbeats”

The LHCb measurement allows students to extract the lifetime of the D0 meson after having studied and fitted an invariant-mass distribution of identified kaons and pions. The next step is to compare and discuss properties of D0 and D0 decays.

All of these educational packages are tuned and expanded to follow the LHC’s “heartbeats”. The intention is for the IMCs to bring measurements for new discoveries in the coming years.

A model for science education

The IMCs have led to other masterclass initiatives. National programmes bring masterclasses to students in areas far from the research institutes that host the international programme. In several countries, programmes for teachers’ professional development include masterclass elements, as does CERN’s national teacher programme. Masterclasses also reach locations other than schools, such as science centres or museums, and other fields of physics, including astroparticle and nuclear physics, have embarked on national and international masterclass programmes.

The largest national programme is the German four-level “Netzwerk Teilchenwelt”, which has been active since 2010. In its basic level, more than 100 young facilitators, mostly PhD and Masters’ students from 24 participating universities and research centres, take CERN’s data to schools. Throughout the year, on at least every other school day, a local masterclass takes place somewhere in Germany. Annually, about 4000 students are invited to further qualification and specialization levels in the network, which can lead to their own research theses. Another example is the Greek “mini-masterclasses” at high-schools, which are usually combined with virtual LHC visits where students link with a physicist at the ATLAS or CMS experimental areas.

Elements of particle-physics masterclasses for teachers’ professional development have become standard in most of the national teacher programmes at CERN and in countries such as Austria, France, Germany, Greece, Italy and the US. Masterclasses for the general public have taken place in science centres in Norway and Germany.

Other physics fields are also using the masterclasses as a model for physics education and science communication. For example, in the UK, nuclear-physics masterclasses cover nuclear fusion and stellar nucleosynthesis. Astroparticle physics is also joining the masterclass scene. In Germany, the Netzwerk Teilchenwelt hosts masterclasses that use data from the Pierre Auger Observatory to reconstruct cosmic showers or energy spectra, or data on cosmic muons that the students take themselves using Cherenkov or scintillation detectors. Since 2012, students at the Notre Dame Exoplanet Masterclass in the US have used data and tools from the Agent Exoplanet citizen science project run by the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network to measure characteristics of exoplanets from their effects on the light curves of stars that they orbit during a transit. New international masterclasses on the search for very high-energy cosmic neutrinos at the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole will connect three countries in May 2014, with more countries joining in 2015.

Behind the scenes

An international steering group manages the IMCs in close co-operation with IPPOG. Co-ordination is provided through the Technische Universität (TU) Dresden and the QuarkNet project in the US, and funding is provided by institutions in Europe (CERN, the European Physical Society and TU Dresden) and the US (the University of Notre Dame and Fermilab). While the co-ordination based at TU Dresden is responsible for the whole of Europe, Africa and the Middle East, co-ordination through QuarkNet covers North and South America, Australia and Oceania and the Far East. Co-ordinators are in close contact with all of the participating institutions. They issue circulars, create the schedule, maintain websites, provide orientation and integrate new institutions into the IMCs. As QuarkNet is a US programme for teachers’ professional development, the co-ordination also includes visiting and preparing educators at schools and at IMC institutions.

One of the highlights of the IMCs is the final video conference, where students present and combine their results

One of the highlights of the IMCs is the final video conference, where students present and combine their results with other student groups and moderators at CERN or Fermilab. Co-ordinators take special care to create the schedule so that every video conference is an international collaboration that lets the students explore part of the daily life of a particle physicist, doing science across borders. Young physicists at CERN and Fermilab moderate the sessions and represent the face of particle physics to the students. The co-ordinators maintain excellent collaboration with the moderators, for example arranging training and monitoring video conferences.

IPPOG – an umbrella for more

The IMCs in the LHC era are a major activity of IPPOG, a network of scientists, educators and communication specialists working worldwide in informal science education and outreach for particle physics. Through IPPOG, the masterclasses profit from scientists taking an active role, conveying the fascination of fundamental research and thereby reaching young people. IPPOG offers a reliable and regular discussion forum and information exchange, enabling worldwide participation. In addition to organizing the IMCs and hosting a collection of recommended tools and materials for education and outreach, IPPOG facilitates participation in a variety of activities such as CERN’s new Beam Line for Schools project and the celebrations for the organization’s 60th anniversary.

IPPOG is poised to support recommendations outlined in the 2013 update to the European Strategy for Particle Physics and the US Community Summer Study 2013, to engage a greater proportion of the particle-physics community in communication, education and outreach activities. This engagement should be supported, facilitated, widened and secured by measures that include training, encouragement and recognition. Many individuals, groups and institutions in the particle-physics community reach out to members of the public, teachers and school students through a variety of activities. IPPOG can help to lower the barriers to engagement in such activities and make a coherent case for particle physics.

The organizers of the IMCs expect and welcome new partners. For more about the programme, visit http://physicsmasterclasses.org/. For more about IPPOG, see http://ippog.web.cern.ch. For the Netzwerk Teilchenwelt, visit www.teilchenwelt.de; for the Mini-Masterclasses, see http://discoverthecosmos.eu/news/87; and for QuarkNet, see http://quarknet.fnal.gov/.

The LHC and beyond

The International Masterclasses make use of real events from LHC experiments through a variety of activities:

• ATLAS Z-path – http://atlas.physicsmasterclasses.org/en/zpath.htm

• ATLAS W-path – http://atlas.physicsmasterclasses.org/en/wpath.htm

• CMS measurement – http://cms.physicsmasterclasses.org/pages/cmswz.html

• ALICE ROOT-based – http://aliceinfo.cern.ch/public/MasterCL/MasterClassWebpage.html

• ALICE – www-alice.gsi.de/masterclass/

• LHCb measurement – http://lhcb-public.web.cern.ch/lhcb-public/en/LHCb-outreach/masterclasses/en/

• iSpy-online – www.i2u2.org/elab/cms/event-display/

• Hypatia – http://hypatia.phys.uoa.gr/

• Minerva – http://atlas-minerva.web.cern.ch/atlas-minerva/

At the same time, activities are extending beyond particle physics:

• Nuclear physics – www.liverpoolphysicsoutreach.co.uk/#/nuclear-physics-masterclass/4567674188

• Exoplanet Masterclass – http://leptoquark.hep.nd.edu/~kcecire/exo2013/

• IceCube – http://icecube.wisc.edu/masterclass/participate