Ulrich J Becker, professor emeritus at MIT, passed away on 10 March at the age of 81. He was a major contributor to the L3 experiment, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer and the advancement of international collaborations in high-energy physics.

Becker was born in Dortmund, Germany, on 17 December 1938 – the day that nuclear fission was discovered in Berlin. As a young man, he was adept as an electrician, coal miner, and even in steel smelting, but he was more drawn to physics. He studied at the University of Marburg and obtained his PhD in Hamburg, focusing on the photo-production and leptonic decays of vector mesons.

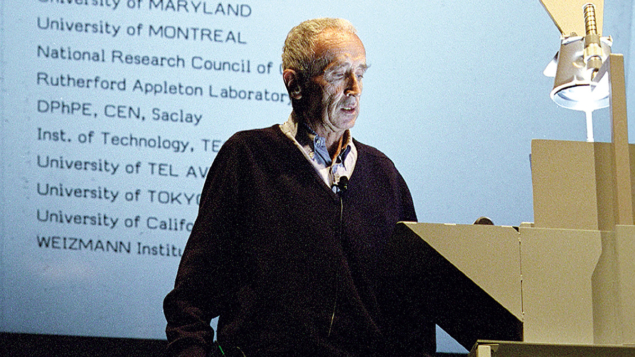

In late 1965 Becker met Sam Ting, who admitted him to his group at DESY using the 6 GeV synchrotron to measure the size of the electron. It was a complementary match: Becker was a dogged researcher with detector and hardware acumen, and Ting was a master in scientific organization and politics. They presented their results at the XIIIth International Conference on High Energy Physics at Berkeley in 1966, showing that electrons have no measurable size, which contradicted earlier results.

In 1970 Becker joined the MIT faculty, where he found mentors including Victor Weisskopf and Martin Deutsch. He was promoted to associate professor in 1973, and the following year he began designing a precision spectrometer for Brookhaven National Laboratory. He joined a group led by Ting which used the spectrometer to search for heavy particles produced when protons were smashed into a fixed target of beryllium. Instead, the team recorded an unexpected bump in the data corresponding to the production of a heavy particle with a lifetime that was about a thousand times longer than predicted.

Meanwhile, MIT alumnus Burton Richter was reviewing data from Stanford Linear Accelerator Laboratory when he too found what looked like a long-lived heavy resonance. Ting flew to Stanford in November and he and Richter quickly organized a lab seminar. They presented their discovery of the J/Ψ particle, a bound state of a charm quark and antiquark, on 11 November 1974, sparking rapid changes in high-energy physics. One of Becker’s favorite stories was when he went to Munich in 1975 to share their finding, and Werner Heisenberg interrupted to comment: “Whenever they don’t know what it is, they invent a new quark.” To which Becker replied: “Look, Professor Heisenberg, I’m not arguing whether this is charm or not charm. I’m telling you it’s a particle which doesn’t go away.” A deadly silence followed before Heisenberg replied: “Accepted”. Ting and Richter shared the 1976 Nobel Prize in Physics for the J/Ψ discovery. If only one of the groups, MIT, had discovered it, it is likely that Becker would also have shared in the prize.

He enjoyed reviving broken and abandoned mechanical items.

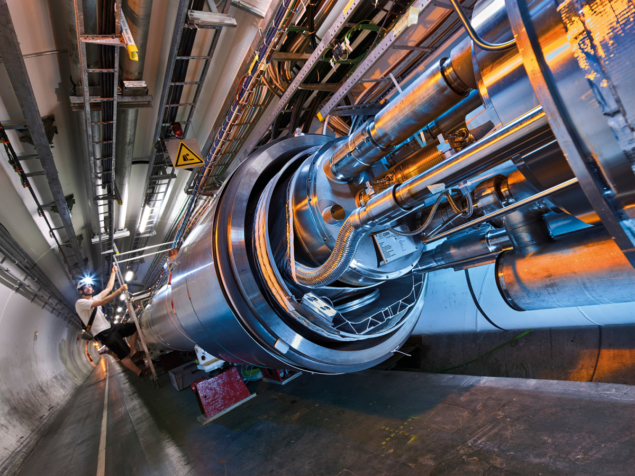

Becker, who was made a full professor at MIT in 1977, developed several other major instruments which were the catalyst for discoveries. His large-area drift chamber would provide large acceptance coverage for experiments, and his drift tube enabled physicists to measure particles near the interaction point. Those developments led Becker to design and build the huge muon detectors for the MARK-J experiment at DESY, which resulted in the discovery of the three-jet pattern from gluon production. Becker then led hundreds of colleagues in designing the muon detector for the L3 experiment at LEP. He also made important contributions to advancing international collaboration in high-energy physics, for example involving China.

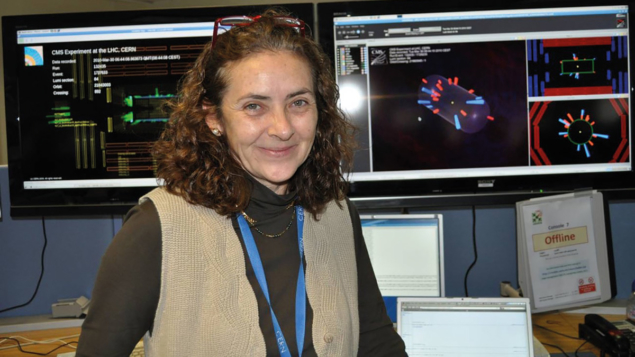

In 1993, Becker started to work with MIT’s team on building an Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS) — another Ting project which was born when he and Becker were on a coffee break while working on L3. The first AMS detector flew in the Space Shuttle in June 1998 and gathered about 100 hours of cosmic-ray data. Becker then went on to help design the transition radiation detector for AMS-02, which has so far collected more than 150 billion cosmic-ray events from its position on the International Space Station.

He enjoyed reviving broken and abandoned mechanical items. One of his biggest renovations was MIT’s cyclotron, which he converted into one of the biggest functioning magnets in the country, with a strength of up to 1 T. He used it to develop particle detectors for the International Linear Collider, and to characterise gas mixtures for the design of drift and other gas detectors in different magnetic and electric fields.

Becker was a mentor to many great physicists, and invested much to ensure his students received an excellent education. In 2013 he transitioned to emeritus status, but still he came in every day to mentor students. At the age of 81, he even picked up Python to continue his craft. His friendly approach and deep understanding of physics made him a superb teacher, even if his style was highly individual.

Our community has lost an excellent researcher and teacher, and a wonderful colleague and human being. Ulrich Becker is survived by his wife Gerda, his three children and two grandchildren.