edited by Katri Huitu, Valery Khoze, Risto Orava and Stefan Tapprogge, World Scientific, ISBN 9810247346, £48.

These are the proceedings of a workshop held in Helsinki, in 2000, which covered both theoretical and experimental aspects of the topic.

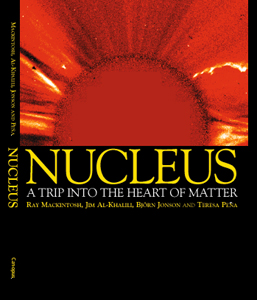

by Ray Mackintosh, Jim Al-Khalili, Björn Jonson and Teresa Peña, Canopus Publishing, ISBN 0953786838, £14.95.

A lot of care and attention have gone into this attractive book. The authors are all eminent nuclear physicists who have developed an interest in outreach and public awareness of science, and it shows. Around their text, the book has been tastefully designed and illustrated, depicting the quest to unravel the ultramicroscopic structure of matter, particularly during the 20th century.

The keynote is the book’s nuclear physics standpoint. Fundamental particles and their constituent quarks and gluons are only mentioned in passing, but this is no obstacle.

Physics is a collection of natural phenomena, but it needs physicists to interpret it and to make it understandable, and the book continually underlines the role played by pioneers like Rutherford, Hofstadter and Mottelson. After introducing the nuclear structure of our everyday world, it goes on to point out a wider nuclear landscape – the wealth of synthetic unstable isotopes and their production, behaviour and properties.

As well as its ominous implications for warfare and its still-considerable contribution to power supply, nuclear physics has a range of applications in medicine, industry, the environment and even the home, essentially through the manufacture of radioisotopes, which again are well documented and illustrated in this book.

Nuclear physics provides a prolific source of power on many different scales. At the beginning of the 20th century, physicists did not even understand what made the Sun shine. The subsequent understanding of the role of nuclear mechanisms in astrophysics evolved slowly through the work of major figures, like Hans Bethe and William Fowler. At this point of history the book strangely deviates from its policy of presenting cameo portraits of key researchers.

Modern cosmologists try to work out what happened in the first tiny fraction of a second after the Big Bang. The universe had reached the ripe old age of one second before any nuclei appeared on the scene. Having carefully traced the role of nuclei back to this entry point, the book ironically ends.

There are a few minor errors – Rutherford is introduced twice and a bubble chamber photograph of the discovery of the positron is upside down. Perhaps the advertised selling price is another error. How can such an attractive book be made available so cheaply? Nucleus is one of the first books to be produced by Canopus, a new force in popular science publishing. Buy it while stocks last.

by G C Lowenthal and P L Airey, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521553059.

At a time when applications of nuclear and particle physics are gaining ground in environmental sciences, life sciences, nuclear energy and materials research, this book is a welcome new arrival. Mainly it addresses practical applications in industry, but it also covers medical and energy sciences. The development of novel concepts in radiation detection and particle accelerators for basic subatomic physics, with potential for future applied use, make it particularly timely.

The first half of the book is dedicated to the basics of nuclear physics for non-expert readers. For this reason, some of the latest phenomena are not covered and the terminology is not always in line with that of the most recent literature of nuclear science. The book provides information for practical work with radionuclides, including the basics of radioactive decays, interaction of radiation with matter and radiation detectors. The guiding principles for working with radioactive sources in both industrial and laboratory environments are well covered. Procedures for estimating dose rates in different environments are also discussed. Measurements and results receive attention, with the book providing guidance for data analysis from radiation measurements.

Applications in industry and the environment are covered in the second half of the book. There is a detailed description of techniques based on the interaction of radiation with matter, using examples covering transmission, scattering, absorption and activation by beta particles, protons, alpha particles, photons and neutrons. Applications discussed include paper analysis, moisture meters, neutron radiography, multi-element analysis, sterilization and polymerization. Radiotracer techniques are also broadly covered, with detailed formulation in flow measurements with radioactive tracer isotopes. Radionuclides in the environment are covered, both for naturally occurring and for man-made radioisotopes.

In short, this book is a sound addition to the limited literature dealing with applications of radioactivity and radionuclides. It also serves as a useful reference source for those working professionally with accelerators and radioisotopes.

by Peter K F Grieder, Elsevier Science, ISBN 0444507108, 190.59 euros/$207.

This book is a remarkable collection of graphs, tables, data and relevant discussions about cosmic-ray physics. As the subtitle, Researcher’s Reference Manual and Data Book, suggests, this is neither a text nor a tutorial, but a valuable resource for scientists in cosmic-ray research and related fields of physics and astrophysics.

In 1984 Peter Grieder of Bern co-wrote, with O C Allkofer of Kiel, a 379-page reference manuscript in the Physics Data series of the Karlsruhe Fach-informations-zentrum (Cosmic Rays on Earth ISBN 03448401) which contained much useful data and has been widely used. Following the death of his co-writer, Grieder has undertaken the daunting task of revising, updating and expanding the work by himself. In view of the significant quantity of new data appearing over the past two decades, this is most appropriate. The result is a comprehensive 1112-page, hardcover volume.

Over the past two decades there has been a significant migration of physicists away from traditional accelerator-based particle physics into particle astrophysics (the current, more erudite, term for cosmic-ray physics). This is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in the formation and direction of major cosmic-ray collaborations by Jim Cronin and Sam Ting, both of whom are Nobel laureates in accelerator-based particle physics.

Mature physicists moving into cosmic-ray-related research from other areas should find this book a particularly valuable source of cosmic-ray knowledge. Of course, it is not intended to replace the role of classic texts such as Thomas Gaisser’s Cosmic Rays and Particle Physics. It covers cosmic rays in the atmosphere, at sea level, underground, underwater and under ice; the primary radiation; solar phenomena; and cosmic-ray history.

In view of the current lively interest in neutrino oscillations and the interpretation of data from Kamioka, Gran Sasso, Homestake, Soudan, Lake Baikal, Antarctica, the Mediterranean Sea and elsewhere, these detailed discussions are highly useful. They may also reflect Grieder’s close connections with the DUMAND and NESTOR underwater detector programmes.

There is a substantive discussion of, and data compilation related to, neutrinos, including both atmospheric and solar neutrinos, the latter as part of the chapter on heliospheric phenomena.

There are also comprehensive chapters in each section devoted to protons, neutrons, heavier nuclei, electrons, positrons and gamma rays (as well as muons and neutrinos). The existing data relevant to major problems and projects currently in progress are well presented. This includes such issues as the primary cosmic-ray spectrum and composition above the GZK cut-off; the confusion concerning the elemental composition in the neighbourhood of the “knee”; questions surrounding the primary antiproton flux; and the limits on primordial antimatter cosmic rays. The author presents this vast accumulation of data without editorial prejudice, so he resists noting which data should be regarded as most reliable and which should be accepted with scepticism.

The latter portion of the book includes useful reference material, such as the “optical, etc properties of water and ice”; parameters of the atmosphere (pressure and temperature versus height above sea level); the “solar elemental abundances”; and tables and graphs of muon dE/dx versus energy in various substances. There is even a full-page table of the many cosmic-ray observing stations around the globe – past and present – together with the altitude and atmospheric overburden of each.

This book is certain to become a standard reference for scholars in the cosmic-ray community, as well as for students and for other physicists and astrophysicists whose activities interface with cosmic-ray issues. Certainly, many of this book’s graphs and tables will be superseded by more precise, forthcoming data from Superkamiokande, Kascade, ACCESS, IceCube, the Pierre Auger project and the many other ongoing and future cosmic-ray research activities, but its value as a reference will surely continue well into the 21st century – until someone else with Grieder’s breadth of comprehension and boundless energy steps forward to undertake another revision.

by Edmund Wilson, 2001 Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198508298 (pbk), ISBN 0198520549 (hbk).

Having designed real accelerators himself and having spent the last nine years at the helm of the CERN Accelerator School, Edmund (Ted) Wilson is well placed to write this book, which is an excellent introduction to a fascinating field of activity.

The book provides students with an understanding of the basic physics of particle accelerators and conveys the flavour of their technology and applications. As such it fills a useful gap between journalistic descriptive works and landmark reference books, in that it treats the reader as an intelligent scientist or engineer, willing to invest some time in the understanding of the principles invoked, yet presents the information in an attractive and digestible form.

In this respect the introduction to the subject via the history of accelerators is certainly a good way to keep the reader interested while nevertheless introducing essential concepts. But, as we all know, to understand does not necessarily mean to learn, and the inclusion of a small set of exercises at the end of each chapter is an effective way of encouraging those who really want to learn about, rather than become simply acquainted with, the subject. Having the answers at the end of the book is a real encouragement to try the exercises.

After the historical introduction to the subject, the main body of the book is devoted to the behaviour of beams of particles and the methods that are used to focus, bend, accelerate and control them. In addition to classical linear theory, the mechanisms and problems associated with nonlinearities, resonances, space charge, instabilities and synchrotron radiation are all introduced.

There follows a well balanced description of the increasingly varied applications of these devices. The final chapter, giving an outline of promising ideas for accelerating beams of particles that have not yet resulted in practical machines, should stimulate students who are interested in pursuing this path into adopting or inventing new techniques to achieve evermore efficient machines.

This is not the only book on the subject, but it does serve as a well written and well balanced introduction – not only for students, but also for anyone drawn into the field in a related scientific, engineering or administrative capacity. The layout of the book is clear and the text is backed up with a wealth of good illustrations. Readers requiring a deeper insight into one aspect or another of the subject are invited to consult more specialized works, all of which are cited in the excellent bibliography.

Last year the US particle physics community mounted one of its periodic long-range planning exercises to provide a roadmap for the subject over the coming decade. The recommendations from this study, which was conducted by the High-Energy Physics Advisory Panel (HEPAP) of the US Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation, have been published.

As one conduit to this review, a Young Physicists Panel (YPP) was established by Bonnie Fleming of Columbia, John Krane of Iowa State and Sam Zeller of Northwestern to provide a platform and consensus view for younger researchers. Originally the YPP hoped to provide a brief summary document. However, the survey revealed instead that most respondents did not have a single opinion to convey, making the conclusions more difficult to digest, but at the same time probably more valuable.

To be most useful to HEPAP, the survey, entitled “The future of high-energy physics”, focused on US aspects and needs. Although initially designed for and oriented towards “young” physicists (defined as those yet to achieve a permanent position or tenure), the study was extended to all particle physicists, both inside and outside the US. There were some 1500 replies, most of which were received via the Web.

The survey began with a request for demographic and personal information – current career status, geographical origin, place of work, type of physics done and size of collaboration. The highest profiles to emerge were of a North American working in North America, or a European working in Europe, on collider physics in a team of 500-1000 people. No surprises there.

The next series of questions were aimed at “balance versus focus”, asking what sort of research should be carried out at the next major physics machine to be built, how many detectors it should have and what sort of physicists it should employ.

In this section the emerging picture was of a machine supporting a diverse range of physics, with at least two detectors, employing comparable numbers of theorists, phenomenologists and experimentalists. An extra question showed that it is considered important for high-energy physics laboratories to host an astrophysics effort. Some do, some are in the process of doing so, and other laboratories have yet to satisfy this demand.

A section covering “globalization” lumped together anything to do with big science being concentrated at major centres. Most respondents admitted to seeing their detector at least weekly, so obviously they have easy access and would rather have it this way than be near their supervisor. A hands-on hardware requirement was seen as very important and, if a research centre was situated outside the US, national or regional access via a staging post was considered the best possible alternative to being centrestage.

Answers to specific questions on outreach underlined that particle physics is not doing nearly enough to communicate with either the relevant funding agencies or the general public. Half of the replies indicated that physicists were ready to dedicate more time to this important activity. (It is our opinion at CERN Courier that while this is very commendable, it is one thing to tick a box, but quite another to deliver. Unfortunately, few physicists have the imagination and commitment to contribute significantly to outreach activities.)

The most revealing part of the survey was perhaps the one that asked participants why they had been attracted to particle physics originally and why they had remained in the field. The answers reveal that intrinsic scientific interest dominated the decision, whether for newcomers or for those further down the line. Science is clearly interesting, at least to some people, and here is a possible message for outreach.

Also very prominent was the opinion that a lack of jobs could drive young people out of the field. Another visible signal indicated that not enough talented physicists are retained. The big question that faces the field now is how to rectify this.

The remaining sections of the YPP survey focused on physics issues, and these were largely mirrored in the HEPAP recommendations. However, it was clear that opinions about the siting of future machines were polarized according to geographical base (North America or Europe). While most tenured US scientists think that it is important to have a major new facility in the US, this view is not mirrored among younger scientists.

With big issues at stake, casting a wider survey net could reveal a more global consensus within the physics community on the way to go forward.

First and foremost, CERN and the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) are centres of scientific excellence. To mention just a couple of examples, at CERN, physicists discovered the massive particles that are responsible for radioactivity and made detailed measurements that established their underlying theory, resulting in two Nobel Prizes. JINR continues to play a pioneering role in both the discovery and the study of superheavy elements, one of which bears the name dubnium.

JINR and CERN are also living evidence that science knows no boundaries. CERN has 20 member states; JINR has 18. The two organizations were both founded in the years after the Second World War to enable European and other countries to contribute to fundamental physics in ways that they could not afford individually.

Now the two organizations have several member states in common, which was impossible during the Cold War. Nevertheless, CERN and JINR collaborated actively during that dark period, extending their hands to each other across the Iron Curtain. Consequently, they were able to seize the scientific and human possibilities opened up by the fall of the Berlin Wall.

JINR is now one of CERN’s most valued international partners. It has joined CERN in many experiments using CERN’s accelerators. Thousands of students have attended the advanced physics schools that have been organized jointly throughout Europe since the 1960s. Many friendships have been formed there, which have turned into international scientific collaborations that now span the world. Hundreds of JINR-affiliated scientists and engineers are now working with CERN and its other international partners on the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) project. Working together, physicists will use the LHC to study basic questions in physics, such as the origin of mass and the nature of the dark matter filling the universe.

The LHC project presents unprecedented technical challenges, such as in the areas of superconducting technology, cryogenics and informatics. In the latter field, the World Wide Web was invented at CERN in the early 1990s to enable physicists around the world to share data from LEP and analyse them together. The requirements of the LHC are driving the next stage in the evolution of the Internet – the Grid – which will enable people anywhere in the world to use remote computer power, just as today the power grid enables us to use electrical energy without knowing where it was generated.

The LHC is also an unprecedented international collaboration. The accelerator is being built with important contributions from JINR, Russia, the US, Japan, India and Canada, as well as CERN and its member states. The LHC experiments are open to scientists worldwide, who currently originate from more than 80 countries. A special role is played by the International Association for the Promotion of Co-operation with Scientists from the New Independent States of the Former Soviet Union (INTAS) and the International Centre for Science and Technology (ISTC), which have facilitated the participation by many scientists and engineers from Russia in particular.

JINR is also making many important contributions to the LHC experiments, notably to CMS, ATLAS and ALICE. The JINR contibution is both direct, through its staff working at home and at CERN, and indirect, through its coordinating role for the contributions made by Dubna member states.

CERN has fostered some unique collaborations. For example, for many years it has had Indian and Pakistani physicists working together, as well as scientists from both Beijing and Taipei. Now an Iranian group is starting to work at CERN alongside Americans. In my own area – theoretical physics – CERN has had a postdoctoral fellow from Afghanistan, and another from Iran has recently written joint scientific papers with a CERN staff member from Israel.

Many of us fear that the openness of the international system is under unprecedented attack. Scientists must thus stand together to defend our common values. This joint exhibition by JINR and CERN clearly displays our common vision. We stand for scientific excellence, international understanding, dialogue to find common solutions to common problems, openness, development and progress. In the words of the Russian empress Elizabeth Petrovna, which were quoted at the exhibition, “Enlightenment of mind eradicates evil.”

CERN and the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, Dubna, near Moscow, were set up in 1954 and 1956 to provide a physics foundation for international collaboration. CERN set out to rebuild Western European science after the Second World War; Dubna had a similar mission for the socialist countries of Eastern Europe and further afield. Over the years, these two political spheres, isolated from each other during the Cold War, have grown closer.

A news magazine is about developments. As scientific developments have unfolded over time, the many issues of this magazine have helped to reveal the history of particle physics.

The rate of particle physics discoveries, which was tumultuous during most of the 20th century, has slowed down. In the final years of the 20th century our knowledge and understanding reached a plateau in the Standard Model (few physicists share Murray Gell-Mann’s passion for coining imaginative words where they matter).

From this plateau, the view has widened. High energy means high temperature, so that particle physics and astrophysics, and even cosmology, find themselves more and more on common ground, tracking the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang in a still-hot universe. Not that long ago it would have been inconceivable for particle physicists to be interested in what happens in the sky. Now the latest news on microwave background radiation, supernovae, black holes and gamma-ray bursters is followed enthusiastically at major particle physics meetings. Astrowatch is one of the most popular features of this magazine.

The rate of pure particle physics breakthroughs may have slowed temporarily, but an accompanying rush of technological innovation continues and even accelerates. To seek the elusive particle signatures of tomorrow, large experiments involving thousands of ingenious researchers scattered across the globe are today exploiting new materials and pushing innovative techniques to achieve what seemed impossible only yesterday.

The World Wide Web is just one example. Take telecommunications, microelectronics, cryogenics etc. At no time in history has technology been advancing so rapidly. Fundamental science is the spring from which many of these developments flow. Physicswatch monitors this evolution.

Visiting CERN recently was Mike Lazaridis, the president and co-chief executive of Research in Motion of Canada. He is a leading designer and manufacturer of wireless communications equipment. As a great believer in the importance of fundamental physics for society, Lazaridis is personally funding the Perimeter Institute in Southwestern Ontario – an institute dedicated to theoretical physics.

Lazaridis said: “Theoretical physics gave rise to virtually all of the technological advances of present-day society. From lasers to computers and from cellphones to magnetic resonance imaging, the road to today’s technological developments was based on yesterday’s groundbreaking theoretical physics.”

A continuing theme at CERN is international collaboration. The universal culture of physics brings people and nations together, surmounting political and other barriers. CERN was the first example of scientific international collaboration in post-war Europe. As well as furthering research in its member states, CERN helped to catalyse new contacts further afield, where contact was difficult because of politics or recent history. Even in the depths of the Cold War, there was contact between scientists at CERN and their counterparts in the Soviet Union.

The Geneva laboratory has gone on to become an even wider stage. Building the detectors for CERN’s proton antiproton collider in the late 1970s and early 1980s demanded a major international effort, mainly in Europe. However, even this is being dwarfed by the operations now under way worldwide to construct the Large Hadron Collider and its mighty detectors. While G8 powers and lesser giants naturally play an important role, being part of this effort is a source of great pride for nations that would otherwise not be able to participate in such prestigious research.

Today’s Standard Model may be a plateau of understanding, but it is not the ultimate summit of knowledge. Particle physics is poised to enter the next act in a drama for which the script has yet to be written. To understand a universe of unfathomable complexity will demand fresh insight and imagination.

The new theories…cannot even be explained adequately in words at all.

Paul Dirac

Describing the ultimate physics is a continual challenge. Quantum mechanics pioneer Paul Dirac pointed out: “The new theories…cannot even be explained adequately in words at all.” And that was back in 1930.

Fundamental science attracts keen minds.Working with these intellects is rewarding, but demanding. Articles written for a wide audience are not always welcomed by specialists who quickly point to the verbal inadequacies anticipated by Dirac. In constructing the intellectual cathedral of science, attributing individual recognition is particularly difficult. The world’s great lasting monuments may have been designed by far-sighted architects, but they were built by protracted teamwork.

Words aid comprehension. Francis Bacon (1561-1626) wrote in Novum Organum: “The ill and unfit choice of words wonderfully obstructs the understanding.” In a field where terminology is not always adopted for its transparency (quark fragmentation means exactly the opposite of what it implies), CERN Courier is widely appreciated. Its decoding of physics jargon is particularly welcomed by the world’s media. Above all, it delights in its use of that supremely functional instrument – the English language – which remains highly resilient to the abuse heaped upon it.

Starting with this issue, James Gillies takes over as editor of CERN Courier, succeeding Gordon Fraser, who has been a major contributor to the magazine since his arrival at CERN in 1977 and its official editor since 1986.

The new editor is no newcomer to physics or physics writing. He began his career as a graduate student at Oxford working on CERN’s EMC experiment in the mid-1980s. Moving on to the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (RAL), he then became increasingly interested in communicating science, working for a summer with the BBC World Service Science Unit; setting up a regular local radio science spot; and producing public information material for RAL.

In 1993 he left research to become the head of science at the British Council in Paris. After managing the council’s bilateral programme of scientific visits, exchanges, bursaries and cultural events for two years, he returned to CERN in 1995 as a science writer, and was soon installed as news editor of CERN Courier. He co-wrote, with Robert Cailliau of CERN, How the Web was Born – a history of the World Wide Web, which was published by Oxford University Press in 2000.

CERN Courier magazine has come a long way since it was established as CERN’s house journal more than 40 years ago in 1958.

Soon after the magazine’s launch, it began to reflect particle physics developments worldwide, as well as what was happening at CERN. In 1975 a major world meeting of particle physics laboratory directors underlined the importance of the journal in serving the worldwide particle physics community, and the decision was taken to “go international”, with official correspondents in major research centres feeding in news, and with special arrangements for distribution in certain countries. Hence the paradox of a CERN magazine that is distributed all over the world.

This network of international correspondents is still in place and it is the lifeblood of the magazine. Another important aspect of CERN Courier is the distribution network that exists to get the magazine to its readers.

CERN Courier is published 10 times a year in parallel English and French editions (the official languages for all important CERN documents). For each issue around 18,000 copies of the English edition and 5500 copies of the French edition are printed and distributed worldwide.

With a total of 23,500 copies, CERN Courier is read far beyond the particle physics community, which accounts for about half of the total. Reader surveys have shown that the additional readership is mainly scientist administrators, scientists in other fields and students, all of whom want to keep up with developments in basic physics without wanting to get too involved with details.

In the 1990s it became clear that the magazine could not continue to evolve while being published using CERN’s limited in-house resources. In 1998, responsibility for the production and distribution of the magazine passed to the Institute of Physics Publishing (IOP), in Bristol, England, which now publishes the magazine on CERN’s behalf. The editor at CERN retains responsibility for all of the editorial content, but the 1998 transition was a turning point in the magazine’s development.

The task of distributing each edition of CERN Courier is both complex and challenging. The total print run of each issue weighs around 3 tonnes and has to be sent all over the world. Since IOP entered into a publishing partnership with CERN, it has been improving the distribution performance to shorten the time it takes for the journal to reach its readers. The magazine is available free of charge, so this distribution also has to be as economical as possible.

Readers can receive CERN Courier in two ways:

Coming off the press, each edition of CERN Courier splits into three separate routes:

The Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (RAL) in the UK, DESY in Hamburg and INFN in Frascati play a special role in the distribution of CERN Courier within their respective countries. Because of the logistics involved, RAL receives copies direct from the printer, while the other two centres currently receive their copies via Belgium. An initiative is already under way to establish closer links with these major distribution centres and to enhance the distribution performance further. CERN has a particularly heavy distribution load, sending copies all over the world as well as distributing them within the laboratory.

By the time the magazine arrives on a reader’s desk or is taken from a central pick-up point, its journey will have included rides on trucks, ferries and aeroplanes. It will have been scanned by customs officials and handled by international and national shippers, not to mention being sorted and distributed within major centres.

During 2001 we were able to reduce delivery times by, on average, four days for copies sent to individually mailed addresses. In a similar way, 4-10 days have been cut for those copies travelling to the US. There is still room for improvement, not least because of the rapidly changing world scene for postal and courier services. Soon we will implement a much-needed overhaul of some of the address lists. Readers who receive copies mailed from Europe should soon expect to receive a letter and a reply coupon as well as an issue of the magazine.

There are key people at the major distribution points who ensure that you receive your copy of CERN Courier each month. These are low-profile yet vitally important roles that ensure that mailing lists are up to date and that centres receive enough copies.

We are in contact with most of these key people, but not all. The magazine’s distribution network has in many cases developed by itself. A closer collaboration will help to improve the distribution of the magazine continuously, so if you have a role in this, please contact me.

The Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN) is the direct heir to Enrico Fermi and Bruno Rossi’s eminent pre-Second World War schools of physics. Its purpose remains the same – to investigate the innermost structure of matter, a curiosity-driven research that over the years has led to a deep exploration of nature and that today motivates physicists to “draw a picture of the Big Bang”.

As Giorgio Salvini, former Italian minister for universities and research, recalled, the institute first wanted to equip itself with an accelerator – the most powerful at the time. “Fermi himself had suggested aiming high in energy…as it was new physics,” said Salvini. Fermi – the last truly universal physicist – also suggested building an electronic calculating machine, the first prototype of which at Pisa soon made possible the first commercial computer in Italy.

INFN president Enzo Iarocci recalled the history of the institute and some of its most important achievements: international success linked to the names of Rubbia, Cabibbo, Maiani and Zichichi. During the celebrations, these scientists described their view of the challenges of yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Nicola Cabibbo underlined the international extent of the research. “Discoveries [in this field] do not guarantee immediately profitable applications. Nevertheless, this kind of research stimulates great industrial interest, as experimental requirements continuously force technology to move on,” he said.

After recalling Fermi’s foresight and farsightedness, CERN director-general Luciano Maiani highlighted the INFN commitment to his laboratory and explained the expectations of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and other international projects.

For Antonino Zichichi, the major physics themes to be pursued in the coming years include matter-antimatter symmetry, quark-lepton flavour mixing, supersymmetry and dark matter – all of which are challenges that he views with both enthusiasm and optimism.

Nobel prizewinner Carlo Rubbia looked forward to a spectacular scenario. “The new and fundamental role of particle physics is far from being complete. Recent astronomical observations have demonstrated that 95% of the universe is made of dark and exotic matter and energy, still invisible and unknown: this necessarily implies the existence of new kinds of elementary particle and of elementary vacuum,” he said. Experiments with accelerators, such as the LHC, can offer important contributions, but other avenues of research must not be neglected and they can open the way to new and promising studies. Rubbia added: “It’s time to start a new and fascinating discovery game.”

Included in the proceedings was a meeting entitled “Building the future” at which INFN scientific perspectives in various research fields were considered – from nuclear physics to elementary particle and astroparticle physics. Among those attending were high-school student winners of the INFN contest – From atoms to quarks: a trip to the heart of matter. The aim of the contest was to stimulate students’ curiosity in physics and its fundamental research.

The closing day, dedicated to human resources, traced INFN history through people, recalling the institute’s spirit and tradition, where intellectual authority rules and where human relationships are not submerged by hierarchy.

When INFN was born in 1951 it was paradoxically already 20 years old: its origins date back to Enrico Fermi and Bruno Rossi’s schools of physics and to 1930s research in nuclear physics and cosmic rays. In 1926 Fermi became professor of theoretical physics in Rome, working with a group of brilliant young students who became known as the “ragazzi di via Panisperna” (the via Panispera boys).

The milestone 1931 International Congress in Nuclear Physics held in Rome was the first platform to make the new Italian physics more visible to the external world and it opened the way to an extraordinary fertility of ideas and results by Fermi’s group in particular and within nuclear physics in general.

Soon, national political developments led to anti-Semitism and the disintegration of the group. On 6 December 1938 Fermi and his family left Italy for Stockholm, where he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics. From there he moved directly to the US and Rossi soon followed.

Despite enormous difficulties, research in Italy continued during the Second World War and it eventually led to major scientific and political achievements. It was time for both a national and an international relaunch of research via a general coordination of resources at both a local and a European level.

On 8 August 1951 INFN was created, with its first branches in Rome, Turin, Milan and Padua. Six months later, Edoardo Amaldi was designated general secretary of the institute and was also entrusted with the foundation of CERN.