The opportunity for young scientists to meet with Nobel laureates makes the Lindau meeting a very special occasion. This year it was even more special for CERN, with four young participants from the laboratory and a press event where several of the laureates spoke of their expectations for the LHC. The following extracts give some flavour of their opinions.

David Gross: “a super world”

Gross shared the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physics with David Politzer and Franck Wilczek “for the discovery of asymptotic freedom in the theory of the strong interaction”. He is currently director of the Kavli Institute of Theoretical Physics at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

I expect new discoveries that will give us clues about the unification of the forces, and maybe solve some of the many mysteries that the Standard Model (SM) leaves open. I personally expect supersymmetry to be discovered at the LHC; and that enormous discovery, if it happens, will open up a new world – a super world. It will give the LHC enough to do for 20 years and will help us to understand some of the deepest problems in the structure of matter and elementary particles physics and beyond. Supersymmetry is not just a beautiful speculative idea, it has three incredibly strong vantage points in the LHC energy range: the unification of forces, the mass hierarchy and the existence of dark matter, where its abundance is observed. These three indirect hints from experimental observations all point to a TeV regime that can be naturally accommodated in extentions of the SM that were invented long before these indications appeared.

Gerardus ’t Hooft: “a Higgs, or more”

’t Hooft shared the 1999 Nobel Prize in Physics with Martinus Veltman “for elucidating the quantum structure of electroweak interactions in physics”. He is currently professor of theoretical physics at the Spinoza Institute of Utrecht University.

The first thing we expect – we hope to see – is the Higgs. I am practically certain that the Higgs exists. My friends here say it is almost certain that if it exists, the LHC will find it. So we’re all prepared and we’re very curious because there’s little known about the Higgs except some interaction signs. There could be more than one Higgs, several Higgs, and there could be a composite Higgs, but most of us think it should be an elementary particle… My real dream is that the Higgs comes up with a set of particles that nobody has yet predicted and doesn’t look in any way like the particles that all of us expect today. That would be the nicest of all possibilities. We would then really have work to do to figure out how to interpret those results.

Douglas Osheroff: “lots of new particles”

Osheroff shared the 1996 Nobel Prize in Physics with David Lee and Robert Richardson for “their discovery of superfluidity in helium-3”. He is currently professor of physics and applied physics at Stanford University.

The LHC is an incredible piece of engineering, there is no doubt about that; 27 kilometres of superfluid helium is a mind-boggling thing. However, if you look at any little piece of that, it is a simple technology, carried to the absolute limit of what we could imagine that man would ever do. But of course the most fascinating part of CERN isn’t the cryogenics, it’s the particles that we hope the LHC will produce… If we don’t get the Higgs, that would in fact be a bit more interesting, but I am hoping that there will be lots of new particles and resonances that no one ever expected. That will be really exciting.

Carlo Rubbia: “Nature will tell”

Rubbia shared the 1984 Nobel Prize in Physics with Simon van der Meer for their work that led to the discovery of the W and Z bosons at CERN. Rubbia was director-general of CERN from 1989 to 1993 and is still based mainly at CERN, pursuing a variety of research projects in the fields of neutrino physics, dark matter and new forms of renewable energy.

I think Nature is smarter than physicists. We should have the courage to say: “Let Nature tell us what is going on.” Our experience of the past has demonstrated that in the world of the infinitely small, it is extremely silly to make predictions as to where the next physics discovery will come from and what it will be. In a variety of ways, this world will always surprise us all. The next breakthrough might come from beta decay, or from underground experiments, or from accelerators. We have to leave all this spectrum of possibilities open and just enjoy this extremely fascinating science.

George Smoot: “the nature of dark matter”

Smoot shared the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physics with John Mather “for their discovery of the blackbody form and anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation”. He currently works in the field of cosmology at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and is a collaborator on the Planck project.

For a cosmologist, one of the great things is that cosmology and high-energy physics are merging – they begin to overlap and are necessary for each other. For the LHC, I am very excited because it turns out that one of the missions I am doing, the Planck mission, has had the same schedule as the LHC for 14 years. We’ll probably launch a little later… I am looking forward to hearing about the Higgs, because I’d like to see the Standard Model completed and understood. I’m also hoping that the LHC will begin to unveil extra dimensions, and that will have huge applications across the board. But what I am really looking forward to is supersymmetry or something that shows what dark matter is made of, so I have really high hopes, perhaps too high hopes.

Martinus Veltman: “the unexpected”

Veltman shared the 1999 Nobel Prize in Physics with his student Gerardus ’t Hooft “for elucidating the quantum structure of electroweak interactions in physics”. He is professor emeritus at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

What I expect from the LHC? That’s a big problem. What I would like to see is the unexpected. If it gives me what the Standard Model predicted flat out – the Higgs with a low mass – that would be dull. I would like something more exciting than that. I sincerely hope that we do not find something strictly according to the Standard Model because that will make it a closed thing of which we see no door out, though it is still full of questions. Anything except the two-photon decay of the Higgs… But there is also the possibility that other products might come up because the machine, after all, enters a new domain of energy and will perhaps show us things we didn’t know existed. It’s a very exciting thing for me and my guts can’t wait…

The first presence at Lindau

CERN was first officially present at Lindau in 1971, when I was sent there to talk to Werner Heisenberg about the latter’s future attitude towards CERN. My boss Edwin Shaw, head of the Public Information Office, picked me because I spoke German. This was no easy mission. I was very fearful of speaking to Heisenberg because, in 1969, the Nobel laureate had advised the German government not to finance “Supercern” – a more powerful accelerator at a new site in Europe. For Heisenberg, the era of ever-larger machines continuing to yield important discoveries was ending. A universal formula would answer all outstanding questions in particle physics. His peers strongly disagreed with him and he was persuaded to back the lower-cost 300 GeV project at the existing CERN site.

Simon Newman, CERN (1968–1985).

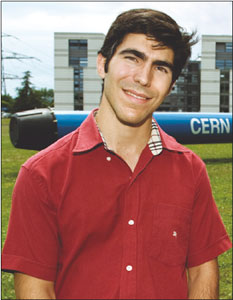

First impressions

For a second year, CERN was offered the opportunity to send young scientists to Lindau. The four selected candidates represented the diverse range of the laboratory’s research. Here are some of their impressions of the event:

“It’s just my second day here in Lindau… We already heard four Nobel lectures and all of them were different and extremely interesting. Some of them were more quiet, some more ready to give advice and even joked during their talks. But even meeting so many students from so many countries is incredibly interesting, to exchange ideas and experiences. I am sure that I am going to learn a lot and remember Lindau for a long time.”

– Magda Kowalska, ISOLDE.

“Lindau is a very nice experience. There are many students from all over the world and many Nobel Laureates from different fields in physics. It is a unique opportunity to meet them and talk in an informal way about many subjects. It is very encouraging for us students to have such role models for our future.”

– Rafael Ballabriga, Medipix/PH Department.

“I’ve had very little time so far to talk to the Nobel laureates, but it’s been really great to talk to other students and learn about what they’re doing and how they work on their research. Generally, when I go to conferences in particle physics, I only talk with particle physicists. Here I get exposed to a lot of other different fields like superconductors and plasma physics. I just had a discussion at lunch about it and that was really fun.”

– Bilge Demirkoz, ATLAS.

“In Lindau, what I find interesting is to learn physics that is actually outside my field of research and to be aware of what other fields of research do in other areas. Yesterday, for instance, we learnt about quantum optics and today, biophysics. It is very interesting to be exposed to all these new ideas – in case we don’t find anything at the LHC and I’ll have to change field!”

– Geraldine Servant, Theory Unit.